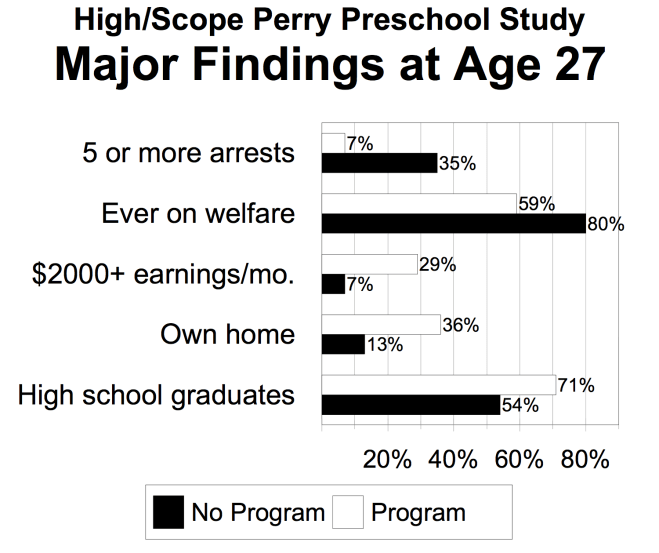

A chart from a study (pdf) on the Perry Preschool Program, an iconic early intervention longitudinal study that began in the 1960s:

After its mention in the SOTU, Travis Waldron makes the case for universal Pre-K:

Expanded childhood education would have substantial benefits for children who receive it. Chicago’s preschool program generates “$11 of economic benefits over a child’s lifetime for every dollar spent initially on the program,” according to one study, and at-risk youth who receive early childhood education are more likely to go to college and less likely to drop out of school, become teen parents, or commit violent crimes. … A universal program would save money by reducing societal and economic costs later in the child’s life, while also increasing social and economic mobility for the children who receive it.

Sharon Lerner recently reviewed the Pre-K program in Oklahoma, calling it “the nation’s brightest model for early education.” Michael Petrelli rebuts with data on Head Start, “the major federal effort in pre-K”:

Any gains [from Head Start] fade out by the third grade. A reasonable question is whether that’s the fault of Head Start or the fault of our dysfunctional public-education system. But there’s little reason for confidence that new federal spending in pre-K, if it looks anything like Head Start, will lead to better results for poor and middle-class children.

Dylan Matthews discounts the data on Head Start:

A randomized trial run by the Administration for Children and Families (ACF), which runs Head Start, found some effects in the first few years for program participants, but those benefits faded away by grade school. Some Head Start supporters, like Danielle Ewen of the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP), argue that this says more about K-12, and that what’s likely happening is that poor quality public schools are actually reversing Head Start’s gains.

Tyler Cowen asks, is “adding on another layer of education, and building that up more or less from scratch in many cases, better than fixing the often quite broken systems we have now?”:

I know well all the claims about “needing to get kids early,” but is current kindergarten so late in life? Why not have much better kindergartens and first and second grade experiences in the ailing school districts? Or is the claim that by kindergarten “it is too late,” yet a well-executed government early education could fix the relevant problems if applied at ages three to four? Would such a claim mean that we are currently writing off many millions of American children, as it stands now?

Grover J. “Russ” Whitehurst weighs in:

It is impossible to reject out-of-hand the hypothesis that children in the Head Start condition will be doing better 20 years from now than children in the control group. But research on the impacts of early intervention consistently shows that programs with longer-term impacts also evidence shorter-term impacts in elementary school. The two iconic preschool interventions that have been the subject of the longest term follow-ups (the Perry Preschool Study, and the Abecedarian Study) both generated impacts in elementary school of preschool program participation. In particular, the Perry Preschool participants were found to have significantly higher scores compared to their control group counterparts on intellectual and language tests at age 7 and on academic tests at age 9.

Sharon Lerner also looks at Perry:

The critics of public pre-K have, for years, hammered on the point that there was only a very small group of Perry students. But in the past decade, early education proponents have amassed the evidence of the great benefits to four-year-olds that have been documented on the state level, too.

Reihan wants more research on pre-K:

[P]re-K programs, whether universal or targeted, might be worth pursuing at some level of investment, but given that we don’t really know much about them, we’d be better served by investing federal dollars into researching existing federal and state programs and developing yardsticks for measuring quality rather than rolling out yet another expansion of pre-K programs

And Sara Mead wonders whether Obama’s proposal signifies a larger shift:

Over the past decade, there’s been a bit of a split in early childhood between advocates of universal pre-k programs designed to prepare 3- and 4-year-olds for school, and advocates who focused on improving childcare and intervention supports for infants, toddlers, and preschoolers (particularly the most disadvantaged) without a specific emphasis on pre-k. In the 2008 campaign, Hillary Clinton came down on the pre-k side of that divide and Barack Obama on the birth-to-five side–and that approach was largely reflected in the President’s first term, with the signature Early Learning Challenge Grant program, inclusion of Nurse Home Visiting in the Affordable Care Act, and expansion of Early Head Start. [Last night’s] speech seems towards an emphasis on pre-k. If that’s correct, what changed?