This time around they gave another meh performance (NYT) on the Programme for International Student Assessment, a standardized test administered every three years to 15-year-old students around the world:

[Americans] score in the middle of the developed world in reading and science while lagging in math, according to international standardized test results being released on Tuesday. While the performance of American students who took the exams last year differed little from the performance of those tested in 2009, the last time the exams were administered, several comparable countries – including Ireland and Poland – pulled ahead this time. As in previous years, the scores of students in Shanghai, Hong Kong, Singapore, Japan and South Korea put those school systems at the top of the rankings for math, science and reading. Finland, a darling of educators, slid in all subjects but continued to outperform the averages, and the United States.

Joshua Keating is one of many bloggers calling out China for gaming the exam:

The three “countries” at the top of the PISA rankings are in fact cities – Shanghai, Singapore, and Hong Kong – as is No. 6, Macau. These are all big cities with great schools by any standards, but comparing them against large, geographically dispersed countries is a little misleading. Shanghai’s No. 1 spot on the rankings is particularly problematic. Singapore is an independent country, obviously, and Hong Kong and Macau are autonomous regions, but why just Shanghai and not the rest of China?

As Tom Loveless for the Brookings Institution wrote earlier this year, “China has an unusual arrangement with the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the organization responsible for PISA. Other provinces took the 2009 PISA test, but the Chinese government only allowed the release of Shanghai’s scores.” As you might imagine, conditions in a global financial capital are somewhat different from the rest of China, a country where 66 percent of children still live in rural areas. … Despite this, we’re likely to see quite a few headlines, as we did in past years, about “Chinese” students outperforming Americans.

An exasperated Rick Hess calls the international tests “a triennial exercise in kabuki theater”:

[T]he whole things provides a depressing excuse for the usual suspects use PISA as an excuse to shill their usual wares. Common Core boosters cheered for that. Dennis van Roekel said it’s all about poverty. Arne Duncan touted the need to embrace Obama administration reforms. Yawn.

Liana Heitin also urges caution when interpreting the results:

TIMSS [The Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study], which came out last year, told a fairly different story – it showed the US scoring better than the global average in math and science, and it had fourth graders improving in math. So maybe US students are improving more in the early grades and hitting a wall in high school – or maybe all of these results should be taken with a grain of salt.

Dana Goldstein sees evidence for the wall theory:

[W]e shouldn’t be surprised that our 15-year-olds are stagnant on PISA. Our best American exam, the National Assessment of Educational Progress, already shows that the performance of our older teenagers has been flat since 1971, even as our elementary school kids – especially poor kids – have improved. Our kids do OK when they’re young, but then stall in high school, time and time again. This fact is backed by two other big international exams that get less airtime, TIMSS and PIRLS, which show that American fourth- and eighth-graders are improving in math, science, and reading, and are actually above average internationally.

Why do our little kids do better than our older ones? Ability tracking may have something to do with it. The PISA results show that in higher-performing nations, all students younger than 15 are exposed to the most challenging math concepts. Nations that track their math instruction by ability, like the US, do worse on these tests, because fewer kids – especially poor kids – are exposed to the deeper conceptual thinking that becomes more important as the grades progress and tests get harder. This helps to account for why, despite the vast privilege of our most affluent students, only 9 percent of American students perform in the top two categories in math, compared with the global average of 13 percent.

Meanwhile, Mark Schneider fears that gifted students have been left behind:

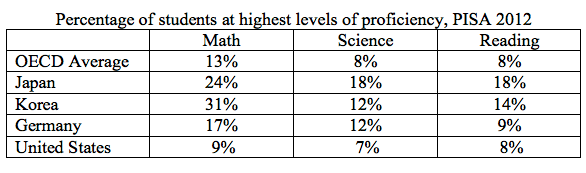

While much of the press coverage will no doubt zero in on our middling performance and the bleak economic future it foretells, a far more disturbing pattern in the data is more likely to hurt us in the long run than will our mediocre average scores. What should scare us is the low percentage of students in the highest levels of performance (PISA level 5 and above).

Even a quick look at these numbers shows how far below some of our major economic competitors the U.S. is. Having such a small percentage of super-performers poses a far greater threat to our economic security and future than being “average” overall does. And it signals the need to reconsider some of the nation’s basic priorities in education policy.

Stephanie Simon reports that poverty explains some, but not all, of the US’s stagnation:

[H]igh-poverty schools in the US posted dismal scores on the PISA tests, akin to countries such as Kazakhstan, Romania and Cyprus. Wealthy schools, by contrast, did very well on all three tests. Students in the most affluent U. schools – where fewer than 10 percent of children are eligible for subsidized lunches – scored so highly that if treated as a separate jurisdiction, they would have placed second only to Shanghai in science and reading and would have ranked sixth in the world in math.

But poverty alone does not explain the lagging results in the US. Vietnam is a poor nation, yet it outscored the US significantly in math and science.

Jonathan Coppage argues that the US shouldn’t worry itself over countries like Vietnam:

We have had our troubles in the intervening years to be sure, but it’s not like the French have overtaken us and are now running away with the world thanks to their superior education. Some scholarly experts warn that even so, we’re in a new era now and decline is once again just around the street corner. The Times quoted Stanford professor Eric A. Hanushek as saying, “Our economy has still been strong because we have a very good economic system that is able to overcome the deficiencies of our education system … But increasingly, we have to rely on the skills of our work force, and if we don’t improve that, we’re going to be slipping.”

With due deference to Dr. Hanushek, I rather suspect things may be the other way around. More rigorously organized cultures like Germany, China, South Korea, France, etc. have crafted their educational systems around the primacy of the test, and have driven their students to excel in it. They also often use these tests to sort their students into the tracks determining what further education they will receive. The United States has a much more free-wheeling system that industrial employers lament is failing to sufficiently supply them with diesel engine experts. What we do have, though (and regular readers brace yourselves), is Silicon Valley. The entrepreneur may be overrated in the GOP at the moment, but a creative culture that fosters innovative risks shouldn’t be taken for granted.