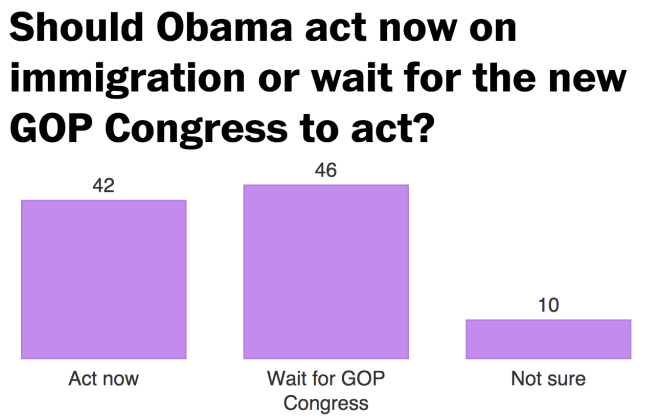

Americans are split on whether Obama should take action:

The split is somewhat counterintuitive, since a strong majority of Americans approve of what is likely to be the key element of the executive action: effectively legalizing millions of immigrants who are here illegally. As Post pollsters Peyton M. Craighill and Scott Clement pointed out over the weekend, 57 percent of those who voted on Nov. 4 favored legalization for these people, while 39 percent wanted deportation, according to exit polls. And even that split was actually narrower than most polls have shown.

But in politics, the process matters too, and many of those who otherwise support legalization also appear opposed to or hesitant about doing so without the regular checks and balances of the legislative and executive branches.

Yglesias bets that the executive action will help Democrats:

Hill staffers who believe in the political power of immigration reform point out that one of the biggest substantive drawbacks of executive action — its very tenuousness — is a political asset. What discretionary authority giveth, discretionary authority may taketh away, after all. If a Republican wins the White House in 2016, there will be no checks and balances to stop him from ordering the deportation of millions of immigrants granted relief by Obama. This dramatically heightens the stakes, not just for the immigrants themselves (who of course won’t be eligible to vote) but for their friends, family, coworkers, and employers.

Of course the higher stakes also involve higher stakes of backlash. But from the viewpoint of the party that benefits from higher turnout, the risk-reward ratio looks good.

Josh Marshall is on the same page:

If there are 5 million people who are affected by this order, the number of people who either have family ties to these individuals or affective relationships with them is much larger. I don’t know if it’s 15 million or 20 million or 40 million. But it’s a lot more than 5 million people who will feel acutely the fate of these people hanging in the balance with the 2016 election. And advocates on both sides of the immigration divide, deporters and pro-immigrant activists will press the issue throughout the 2016 cycle. The 5 million affected can’t vote and won’t be able to for years. But many family members, friends, community members and employers can.

Jennifer Rubin, on the other hand, argues that “it is essential that every Democratic senator and congressman in the new Senate take a vote (be it on the merits or on cloture of a filibuster) on the issue of executive action”:

At some point, they will need to face the voters and explain why they abdicated their responsibility and power to the executive branch. Maybe this is why Sen. Claire McCaskill (D-Mo.) declared about executive action on immigration, “I am not crazy about it,” although she blamed the GOP-controlled House for not acting on the issue. For someone who understood the voters’ intentions well enough to vote against Sen. Harry Reid (D-Nev.) as the new minority leader, surely she could see that the voters dislike unilateral action as much as they dislike the Reid era in the Senate. In any case, make each Democrat vote.

Frum selects another ripe target:

The president’s plan would be costly. The vast majority of those who would gain residency rights under the president’s reported action will be poor. Their low incomes will qualify them for means-tested social programs just as soon as their paperwork is in order. This will not be a small-dollar item. Forty-one percent of the net growth in the Medicaid population between 2011 and 2013 was made up of immigrants and their children. Legalize millions more poor immigrants, and sooner or later, programs from Medicaid to Section 8 housing vouchers to food stamps will grow proportionately. It’s not widely appreciated how much past immigration choices contribute to present-day social spending. In 1979, people living in immigrant households were 28 percent more likely to be poor than the native-born. By 1997, persons in immigrant households were 82 percent more likely to be poor than the native-born. Wittingly or not, U.S. immigration policy has hugely multiplied the number of poor people living in the United States. The president’s plan will put millions of them on the path to qualifying for welfare benefits.

Meanwhile, Bouie dubs Obama’s executive order a defeat for Republicans:

Democrats weren’t going to relent on immigration. Latinos are an important part of the Democratic coalition and key to the party’s effort to change the partisan dynamic in states like North Carolina, Georgia, Texas, and Arizona. And while Latino disappointment wasn’t determinative in this year’s elections, it’s dangerous for Democrats to delay action through 2016, both on the merits—there’s no guarantee of immigration reform in 2017—and on the politics; absent action on immigration, Latinos might just sit out the presidential election, dealing a blow to Democrats in key states like Florida, Colorado, and Nevada. (To that point, it’s no surprise that lawmakers from the latter two have urged Obama to move with executive action on immigration.)