St. Louis, Missouri, 9.01 pm

Talking About The Law Of Rape

by Michelle Dean

At the New Yorker, Harvard law professor Jeannie Suk writes that it’s getting harder to teach the law of rape on campus. She describes a collision course between her desire to teach the hard cases – ones where the parameters of consent may be tested – and the sensitivities of students. Her list of the particulars is sobering:

Student organizations representing women’s interests now routinely advise students that they should not feel pressured to attend or participate in class sessions that focus on the law of sexual violence, and which might therefore be traumatic. These organizations also ask criminal-law teachers to warn their classes that the rape-law unit might “trigger” traumatic memories. Individual students often ask teachers not to include the law of rape on exams for fear that the material would cause them to perform less well. One teacher I know was recently asked by a student not to use the word “violate” in class—as in “Does this conduct violate the law?”—because the word was triggering.

It’s worth saying that I bet some of these organizations and students would quibble with Suk’s description of events. The last sounds particularly apocryphal, I have to say, like it’s gotten misdescribed in the re-telling to better fit a stereotype of campus politics. It’s not just sexual assault stories that tend to get molded to fit an agenda.

It’s harder to object, though, to what Suk describes as a growing fear and apprehensiveness about even broaching the subject of rape:

About a dozen new teachers of criminal law at multiple institutions have told me that they are not including rape law in their courses, arguing that it’s not worth the risk of complaints of discomfort by students. Even seasoned teachers of criminal law, at law schools across the country, have confided that they are seriously considering dropping rape law and other topics related to sex and gender violence. Both men and women teachers seem frightened of discussion, because they are afraid of injuring others or being injured themselves.

While obviously I haven’t faintest idea of what’s specifically been going on at Harvard or other American law schools, I believe that this fear is real because I’ve felt it too.

For most of this past year I took a break from writing about sexual violence. I have what I’d call both strong and considered beliefs on the subject. I’ve spent time talking to and working with victims as a law student and an attorney. I’ve also done my time as a writer in the varied and raucous (and often misrepresented) trenches of the “feminist blogosphere.” My knowledge of the subject is neither that of an amateur, nor even the surface investment of a pundit.

It’s long been apparent to me that no side of this debate is right.

Unqualifiedly believing victims without trying to substantiate their claims doesn’t serve them well, but unqualifiedly doubting doesn’t work either. Calling the current state of the prosecution of rape as “truth-seeking” is misdescribing the process, no matter what evidentiary reform is out there. If you want to teach the hard cases in rape law, I think you have to grapple with those questions carefully. I don’t think it can be enough to simply dismiss that entire part of the discussion as the product of oversensitivity.

Even long experience could not rescue me in the public discussion about Woody Allen earlier this year, though. It was some kind of rape rubicon for me. I hated having to address it. It felt like no matter what I wrote, it was “wrong.” I actually switched jobs to get away from the subject.

But what had caused me to despair of the state of conversation is largely, though not entirely, the opposite of what Suk describes. Whenever I wrote about sexual violence I ended up accused of advocating dogma, of being a bad journalist, of creating an atmosphere where “truth-telling” was impossible. I was also, frankly, tired of being stereotyped as a “feminist blogger” merely for addressing it. If I wrote that there was even some small modicum of value in people believing victims of trauma, I was accused of foreclosing all further discussion.

In other words, knees can jerk on every side of aisle.

That isn’t to say that I felt no pressure from the opposite side. I have also become uneasy with the fact that these rape stories were traffic bonanzas for the various places I write for. And I cringed watching people try to react to the dismantling of the Rolling Stone story in real time according to the well-worn treads of this debate.

But then I come back again to nuance. It’s not a simple matter of dishonest clickbaiting, from my vantage. Over the years I have watched lots of friends turn themselves inside-out emotionally to recount their own sexual assaults over and over in op-eds. They do so out of an honest hope to be heard in the yelling that happens whenever these stories come up. But they also do so at the encouragement of editors who, though well-intentioned, also know full well that the traffic returns could be enormous. And I have my own theories about how all of that intersects with what happened at Rolling Stone.

But like most things in life, it’s complicated. The resistance to nuance is general. Literally no one seems to want to have a careful conversation about any of this. We’re just reiterating the same old positions. Believe them. Don’t. The courts are just. The courts are unfair. Ironically everyone is too busy talking to ask: how can we really have a conversation about this?

Ending The Embargo?

by Dish Staff

Cuba’s release of US citizen Alan Gross is being coupled with a thaw in US/Cuba relations. Both Obama and Cuban President Raúl Castro are set to make public statements today:

Gross’ “humanitarian” release by Cuba was accompanied by a separate spy swap, the [senior administration officials] said. Cuba also freed a U.S. intelligence source who has been jailed in Cuba for more than 20 years, although authorities did not identify that person for security reasons. The U.S. released three Cuban intelligence agents convicted of espionage in 2001.

President Obama is also set to announce a major loosening of travel and economic restrictions in what officials called the most sweeping change in U.S. policy toward Cuba since the 1961 embargo was imposed.

Amanda Taub runs through the basics of the US-Cuba deal. Juan Cristobal Nagel is live-blogging the news. Elliott Abrams prefers the status quo:

On human rights, liberty, individual freedom there have been no changes: Cuba remains a communist dictatorship run by the Castros.

The new Republican-led Congress has a job to do here: to ask whether the President simply forgot about the Cuban people’s rights in his urge to show he isn’t just a lame duck and can still do important things. To make sure that the United States isn’t giving this vile regime a lifeline just when the old age of the Castro brothers is bringing it closer and closer to an end. To limit the benefits to Castro unless and until there are human rights improvements in Cuba.

But Phillip Peters notes that the US political climate has been changing:

As recently as 2000, Cuban Americans broke three-to-one for Republicans in Presidential elections, but no more. In 2012, exit polls showed them splitting 50-50 between President Obama and Gov. Mitt Romney. Considering that the president had mildly liberalized Cuba policies in his first term and Governor Romney was calling for a return to President Bush’s hardline policies, this was a shocking result.

But it was not a fluke: it reflects changing policy preferences in a Cuban-American community increasingly populated by younger generations and more recent immigrants. A 2014 Florida International University (FIU) poll showed that for the first time since its surveys began in 1991, a majority of Cuban Americans, 52 percent, wants to end the embargo. (During the 1990s, five FIU polls showed average 85 percent support for the embargo.) Among those under age 30, 62 percent want to end the embargo and 88 percent want to re-establish full diplomatic relations with Havana.

Larison believes a shift is long overdue:

Normalizing relations with Cuba shouldn’t be seen as a “reward” for the regime. It is the removal of a barrier that has been senselessly maintained for more than five decades. If anyone is being punished by the embargo, it is the people in America and Cuba that would otherwise have productive commercial and cultural exchanges. The U.S. gains nothing by persisting in the embargo. On the contrary, it needlessly alienates Latin American governments and puts the U.S. in the absurd position of defending a Cold War relic. Normalization is twenty years overdue, and nothing will be gained by delaying it any longer.

David Graham notes Republican opposition to normalizing relations:

Republican Senator Marco Rubio of Florida, whose parents were born in Cuba and moved to the United States, has opposed looser travel restrictions. Senator Ted Cruz, another Republican whose father was born in Cuba, also opposes lifting the embargo.

Earlier this month, Jeb Bush, the Republican former Florida governor who on Tuesday announced that he’s “actively exploring” a presidential bid, said, “I would argue that, instead of lifting the embargo, we should consider strengthening it.” As proof that the embargo’s backers aren’t ready to surrender, the Miami Herald reported that “the crowd of donors, the backbone of Cuba’s exiled elite, applauded loudly” when Bush made that proposal. But their view looks more beleaguered than ever today.

And Morrissey wonders how this will play out politically:

This abrupt change will make Florida a very interesting place for Hillary Clinton in 2016. The Cuban exile community has been firm about playing tough against the Castros, but the younger generation may be moving away from that policy. We’ll see.

How Good Are Jeb’s Chances?

by Dish Staff

Nate Silver and his team created “ideological scores for a set of plausible 2016 Republican candidates based on a combination of three statistical indices: DW-Nominate scores (which are based on a candidate’s voting record in Congress), CFscores (based on who donates to a candidate) and OnTheIssues.org scores (based on public statements made by the candidate)”:

Bush scores at a 37 on this scale, similar to Romney and McCain, each of whom scored a 39. He’s much more conservative than Huntsman, who rates at a 17.

Still, Bush is more like his father, George H.W. Bush, who rates as a 33, than his brother George W. Bush, who scores a 46. And the Republican Party has moved to the right since both Poppy and Dubya were elected. The average Republican member in the 2013-14 Congress rated a 51 on this scale, more in line with potential candidates Marco Rubio, Paul Ryan and Mike Huckabee.

So as a rough cut, Bush is not especially moderate by the standard of recent GOP nominees. But the gap has nevertheless widened between Bush and the rest of his party.

The odds Silver gives Jeb:

Betting markets put Bush’s chances of winning the Republican nomination at 20 percent to 25 percent, which seems as reasonable an estimate as any. You can get there by assuming there’s a 50 percent chance that he survives the “invisible primary” and the early-voting states intact and a 40 percent to 50 percent chance that he wins the nomination if he does. It’s a strategy that worked well enough for McCain and Romney.

But Larison argues that “some of the things that have previously been identified as Bush’s ‘strengths’ may no longer be advantages”:

Many conservatives have less patience with Bush’s corporate “centrism” now than there was ten years ago. He may not have a “Mitt Romney problem,” but he has the problem of being corporate America’s favorite candidate. The politics of immigration today is more treacherous for pro-immigration Republicans. Brian Beutler may be overstating the case when he says that Obama’s executive action on immigration has doomed Bush from the start, but he isn’t wrong that being seen as a pro-amnesty politician is a bigger problem for Bush now than it would have been just a few years ago.

Bush is often lauded for his interest in education reform, but this may end up being a serious weakness in a Republican nomination fight.

On that front, Yglesias doubts the Common Core matters:

The thought that the Common Core, of all things, would somehow derail a presidential campaign is a little odd. Federal education policy is a second-tier issue, and as Nate Silver has shown there’s no clear partisan tilt on the Common Core issue among the mass public. Lots of ordinary parents find the Common Core to be somewhat bizarre, but it’s well-supported among education experts.

And, crucially, Jeb is not some kind of ideological heretic on education policy issues. Within the relatively small world of conservative education specialists, he’s extremely well-liked. If party leaders decide that a charge against the Common Core is their #1 goal for 2017, then obviously Jeb is out of luck. But that would be a very weird thing to decide.

Robby Soave disagrees:

It’s true that Mitt Romney managed to win the nomination despite having an unpalatable former position on his election’s pivotal issue—Obamacare. But Romney managed to hedge his previous support for the program by insisting that he never would have taken it to the federal level. Bush, on the other hand, isn’t hedging his Common Core support one iota. He remains the most high-profile supporter of national education standards on the right.

Anyone who expects rank-and-file conservatives to overlook the issue is underestimating the extent of anti-Common Core sentiment among the electorate.

First Read notes that Jeb isn’t particularly popular:

According to our poll, just 31% of all voters say they could see themselves supporting him for president, while 57% say they can’t. He’s more popular among Republicans (55% support, 34% can’t support), which is the second-best GOP score in the poll behind Mitt Romney (see at the bottom). But he fares worse among Democrats (9%-79%) and, more importantly, independents (34%-52%). These numbers follow our Nov. 2014 NBC/WSJ poll, which found Bush’s fav/unfav rating at a net-negative 26%-33%. Of course, this is all subject to change. We could see how Bush — if he runs and bests his GOP competition — could improve his numbers among Republicans and some independents. Nothing can change polling numbers like success. But right now, he’s not Mr. Popular (in large part, we think, because of his last name). And it’s going to take time for him to become Jeb and not a Bush.

Francis Wilkinson asserts that “Bush appears to be demanding that the party now change to suit him”:

Unlike Christie and Romney, two guys who talk tough but shrink from confrontation with the party base, Bush seems determined to run as someone who really does call it as he sees it. It’s an admirable stance and perhaps Bush is sufficiently authentic that it’s the only one possible for him. Call it the audacity of hope. For there is no evidence that his party is eager for anything like straight talk.

Along the same lines, Nate Cohn is unsure the GOP establishment will get its way:

If top G.O.P. donors are indeed choosing between Mr. Bush, Mr. Christie and Mr. Romney, they might not have a better option than Mr. Bush.

But Mr. Bush is not a particularly strong candidate either. He may have friends in the donor class, but he hasn’t run for office in a decade, and he enters with no base of support among the G.O.P. primary electorate. He may not be lucky enough to face an opponent as flawed as Mr. Santorum or Mr. Huckabee. This year’s Republican candidates have the potential to be far stronger than in recent cycles, and if one builds momentum, the establishment’s early, anointed pick might not be able to stop him.

Melting Our Work Ethic

by Dish Staff

It’s another side-effect of global warming:

The paper, by Tatyana Deryugina of the University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign and Solomon Hsiang of the University of California, Berkeley, shows a fairly dramatic negative influence of heat on economic productivity. In particular, they find that, for every 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit (1 degree C) that a given day’s 24 hour average temperature exceeds 59 degrees, economic productivity declines by 1.7 percent. And for a single very hot day — warmer than 86 degrees F — per capita income goes down by $ 20.56, or 28 percent.

The paper is penned in part as a riposte to those who have long assumed that in the United States, our economy is so advanced — and we’re so insulated by things like air conditioning — that a mere hot day can’t throw off the workforce.

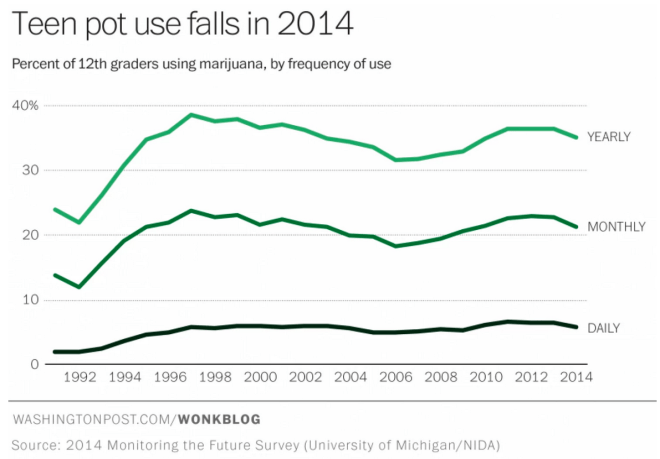

Teens Are Smoking Less Pot

by Dish Staff

Sullum relays the news:

A few months ago, I noted that the National Survey on Drug Use and Health showed no increase in marijuana use by teenagers after 2012, despite groundbreaking legalization measures approved by voters in Colorado and Washington that year. According to the latest results from the Monitoring the Future Study, released[yesterday], marijuana use by eighth-graders, 10th-graders, and 12th-graders fell this year, even as state-licensed pot shops opened in both of those states. It is too early to say whether diversion from adult buyers will increase cannabis consumption among teenagers in Colorado and Washington. But contrary to warnings from prohibitionists, legalization does not seem to be sending a message that encourages teenagers across the country to smoke pot.

German Lopez cautions that “experts say it’s far too early to know the full effects of legal pot sales”:

Mark Kleiman of UCLA and Beau Kilmer of the RAND Drug Policy Research Center cautioned on Monday that even Colorado’s first-in-the-country recreational marijuana industry is far from stable, with prices for recreational pot still higher than prices in the medical market.

“It’s going to be a while before things stabilize,” Kilmer said. Kleiman and Kilmer said they expect recreational prices to drop as more vendors and producers get into the industry, which could make excessive marijuana use more affordable and common.

How Christopher Ingraham frames the debate:

In the early 1990s the federal drug war was in full swing. But teen marijuana use spiked sharply during that period. It didn’t start falling until the late ’90s, when the first states began implementing medical marijuana laws.

This isn’t to say that repealing harsh marijuana laws will necessarily causeteen use to trend downward. But it does at the very least illustrate that it’s impossible to draw a straight line from “relaxing marijuana laws” to “increased teen use,” as [Congressman Andy] Harris and other prohibition enthusiasts do. And there are compelling arguments to be made that taking the marijuana trade off the black market, and letting government and law enforcement agencies, rather than criminals, control the marijuana market, will lead to better overall drug use outcomes among teens.

A Coal-Blooded Killer

by Dish Staff

Brian Merchant highlights a disturbing report (pdf) on India’s coal industry, which is “expected to triple by 2030”:

Today, ambient particulate matter found in pollution is already one of India’s leading killers. According to data presented by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, outdoor air pollution kills nearly 700,000 Indians a year—the next worst killer is smoking. Of that, 80,000 to 115,000 deaths are attributed to emissions from coal plants. By 2030, the toll will have risen to 186,500 to 229,500 a year.

So, by 2030, a given five year period will mean a million dead. And by then more than 42 million will have come down with asthma. The report advocates stricter emissions standards and monitoring, which could help reduce the projected tolls.

Niebuhr On Race In America

by Dish Staff

The evangelical ethicist David Gushee pulled down Reinhold Niebuhr’s early masterpiece, Moral Man and Immoral Society, from his shelf, re-reading it with Michael Brown and Eric Garner in mind. Some background:

Written to pierce any surviving liberal optimism as the Roaring ’20s gave way to the disastrous ’30s, Niebuhr’s primary thesis concerns the effects of sin on human society and, in particular, on human collectivities or groups. Niebuhr says that all human life is marked by sin, especially in the forms of ignorance and selfishness, but at least the individual sometimes demonstrates the potential to rise above ignorance and selfishness to reach rational analysis and unselfish concern for others. Human groups, on the other hand, are both more stupid and more selfish than individuals. They seem especially impervious either to rational or moral appeal, easily prone to self-deception and demagoguery, and apparently needful of the imposition of a power greater than their own power if they are to accede to any changes that cut against their own self-interest.

Though the book focuses on economics, Gushee highlights Niebuhr’s telling comments on race:

Niebuhr writes: “It is hopeless for the Negro to expect complete emancipation from the menial social and economic position into which the white man has forced him, merely be trusting in the moral sense of the white race.” That’s because, as Niebuhr writes throughout, groups which benefit from the existing structure of society have no particular interest in seeing that structure changed.

Moreover, privileged groups have an extraordinary ability to “identif[y] [their] interests with the peace and order of society.” Self-deception reigns among the privileged because, among other reasons, to see reality more truly would place an unbearable moral pressure on such groups to resign privilege in favor of greater justice. Instead, privileged groups call in the forces of state power in the purported interests of the “peace and order” of society as a whole, but in fact to suppress movements of the oppressed for social change and greater justice.

Knowing that only forceful resistance to white privilege has any hope of changing the existing structures of power, Niebuhr ponders whether that pressure will be more effective if it is violent or if it is nonviolent. Niebuhr refuses to draw an absolute distinction between these forms of pressure. He does conclude that “non-violence is a particularly strategic instrument for an oppressed group which is hopelessly in the minority and has no possibility of developing sufficient power to set against its oppressors. The emancipation of the Negro race in America probably waits upon the adequate development of this kind of social and political strategy.”

The Dish recently featured Gushee’s groundbreaking speech on the full inclusion of gay Christians in the Church here.

(Photo: A protester waves a “black and white” modified US flag during a march following the grand jury decision in the death of 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, on November 24, 2014. By Jewel Samad/AFP/Getty Images)

Chart Of The Day

by Dish Staff

Nathan Yau captions:

Reddit user sesipikai tracked his [marriage] proposal during a trip to Italy. He happened to be wearing a heart rate belt, and you can see the rise and fall of beats per minute leading up to the question. Walk. Ask. She says yes. Bask in the happiness. Find a bench.

Full chart here.

Abe Stays On

by Dish Staff

Michael Auslin takes a broad look at the economic implications of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s recent win:

[T]he question now is how far Abe will push the long-awaited structural reforms that he has promised will revitalize the economy and boost wages. There is no longer any excuse for delay, as Abe has another four years ahead of him and no significant opposition standing in his way. A failure to boldly tackle the most difficult reforms, such as in the agricultural sector or in the labor market, not to mention the Trans-Pacific Partnership free trade agreement, will seem doubly damning given Abe’s parliamentary strength. The only reason he doesn’t charge full-steam ahead at this point would be that, deep down, he is not really committed to changing Japan, Inc. That would be a missed opportunity of historic proportions.

Bloomberg View’s editors hope that Abe follows through:

Even Japan’s weak opposition parties more or less acknowledge the good that the first two “arrows” in Abe’s program — massive monetary easing and fiscal stimulus — have done. The Bank of Japan’s bond-buying has driven down the yen 30 percent against the dollar and filled the coffers of companies with global earnings. The unemployment rate is remarkably low; the stock market is rising. Nor is there much quibbling about the direction of Abe’s third arrow — structural changes aimed at improving Japan’s competitiveness.

But it’s not clear that the third arrow will hit its mark:

Tweaks — taxing corporations that sit on their cash rather than investing it or raising wages, for instance — might help around the margins. But the real problem is that for all his energy and verve, Abe has not fundamentally altered the status quo in Tokyo.

Japan’s entrenched bureaucracy waters down reforms almost instinctively. That means small changes are all but certain to be whittled to nothing. Abe’s first two arrows succeeded in part because of their size and shock value: They were designed to change expectations radically, and for a time they did. Abe needs another big bang — something much more than a $25 billion stimulus package.

Back in November, John Cassidy spelled out why he supports Abe:

There’s no convincing reason why a country that is as advanced, well-educated, and hard-working as Japan should remain stuck in an economic rut for decades on end—even if it has run up a great deal of debt. Viable policy options exist to confront deflation, to effect a permanent exit from the liquidity trap, and to get the country growing again, sustainably. These policies aren’t easy to market or enact, but, after years of being saddled with pedestrian leadership, Japan has finally found a Prime Minister, in Abe, who is willing to take some of the necessary measures and confront the people who oppose them.

Be that as it may, Joel Kotkin argues that “it is increasingly clear that the epicenter of Japan’s crisis is not its Parliament, or the factory floor, but in the bedroom”:

Japan has been on a procreation holiday for almost a generation now, with one of the lowest fertility rates on the planet. The damage may prove impossible to overcome. Japan’s working-age population (15-64) peaked in 1995, while the United States’ has grown 21% since then. The projections for Japan are alarming: its working-age population will drop from 79 million today to less than 52 million in 2050, according to the Stanford Institute on Longevity.