The House is working on an authorization to arm the “moderate” Syrian rebels:

The House Armed Services Committee has drafted an amendment to grant authorization to the President to arm and train Syrian rebels opposed to the Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria (ISIS). There are some strings attached, including requiring that the Pentagon report to Congress 15 days before it plans to train and equip the rebels, and provide subsequent updates to relevant committees every 90 days. The language will be included as an amendment to a government funding bill that needs to pass Congress by the end of the month to avert a partial government shut down. Rep. Patrick McHenry (R-N.C.), a key member of the House GOP whip team, said the amendment will pass this week.

But these “moderates” we’re supposed to be counting on seem to be on their last legs, to the point that a major American support group for them disbanded last month:

On August 19, the Syrian Support Group, which had previously arranged a few shipments of nonlethal aid to the Free Syrian Army, sent a letter to donors explaining why the group was shutting its doors. “Over the last year, the political winds have changed,” the letter read. “The rise of ISIS and Jabhat al-Nusra [an Al Qaeda-affiliated opposition force in Syria] and the internal divisions among rebel forces on the ground have complicated our efforts to provide direct support.”

The letter noted that “more significant support” was heading to the FSA from Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the United States, and other governments. But rivalries and rifts within the opposition had impeded the overall effort. “It was difficult to keep things going with the changes in the FSA and its Supreme Military Council and the advent of ISIS,” says Majd Abbar, who was a member of the Syrian Support Group’s board of directors. “It made our operations extremely difficult.”

Then there’s this:

Syrian rebels and jihadists from the Islamic State have agreed a non-aggression pact for the first time in a suburb of the capital Damascus, a monitoring group said on Friday. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights said the ceasefire deal was agreed between IS and moderate and Islamist rebels in Hajar al-Aswad, south of the capital. Under the deal, “the two parties will respect a truce until a final solution is found and they promise not to attack each other because they consider the principal enemy to be the Nussayri regime.” Nussayri is a pejorative term for the Alawite sect, an offshoot of Shiite Islam to which President Bashar al-Assad belongs.

To which Ed Kilgore, who flagged it, remarks:

Perhaps this was all anticipated by the Obama administration and others—indeed, it does help explain the apparent desire of John McCain and Lindsay Graham to go to war with the entire region. But it doesn’t speak well for the idea that anyone who encounters IS understands immediately the organization must be destroyed at any cost lest or the world will come to an abrupt end.

And Allahpundit predicts that our de facto role as Assad’s air force will bring ISIS and Syrian rebel militias closer together, not drive them apart:

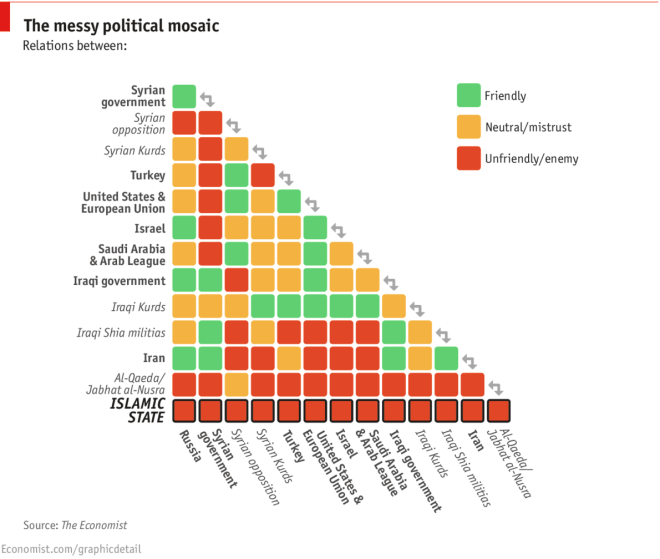

If ISIS’s grip begins to loosen in Sunni areas of Syria as the U.S. pounds them from the air, what are “moderates” more likely to do? Join with their hated enemy, the Shiite Assad, in stamping out ISIS, at which point Assad might turn around and attack the “moderates”? Or join with ISIS and fend off Assad in the name of keeping Iran’s Shiite death squads from cleansing those Sunni areas? Arguably, the more effective we are in damaging ISIS, the greater the risk that our “moderate” partner will turn on us and join the battle against the de facto U.S./Assad alliance. [Richard] Engel sees it coming. Does the White House?

It would appear not. Even though it’s bleeding obvious.