The Clintonite gives the McCain camp some support on the race question. Steve Schmidt returns the favor. I take it as a given that the Clintons are quietly hoping McCain will win this fall. Bill, especially.

Month: August 2008

Dissent Of The Day

A reader writes:

Andrew, love you, babe, but …

If one quarter of the world’s forests were replanted with carbon-eating varieties of the same species, the forests would be preserved as ecological resources and as habitats for wildlife, and the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere would be reduced by half in about fifty years.Yeah, I get a subscription to the NYRB, too, and I when I read this back in May, I nearly jumped out of my chair. Just think about it for a second. ONE QUARTER of the world’s forests. Really? REALLY? Do you have any idea what that would mean?

OK, enough high dudgeon. Here are the problems with Dyson’s fantastical suggestion:

- Turnover — in the long term his plan might work (see RealClimate), but in the short term you would have to replace all the old trees with genetically modified trees. By removing the old ones, you are precipitating the loss of ONE QUARTER (or so) of the world’s terrestrial biomass into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide (Dyson provides no concrete suggestion for what to do with the "old" biomass). And it takes decades for forests and forest soils to mature. As such, forest replacement would at no time provide the short term carbon sequestration that Dyson predicts.

- Disturbance — removing the old trees will disturb the soil. In temperate forest ecosystems, most of the carbon is stored in the soil (tropical forest are different — scant carbon is stored due to poor soil quality). Thus, removing the old trees would lead to MASSIVE atmospheric carbon dioxide release. (Never mind massive erosion.)

- Monoculture — genetically modified trees of the kind prescribed by Dyson would take a long time to engineer, and would come on line in a trickle. Most of the "new" forests would therefore be of a single or a few genetically modified species, and even if they were of the same species as the previous forest (which is technical challenge that we plant biologists find laughably optimistic), in the short run the new forests would be subject to serious disease problems as well as vulnerability to climate change because of their lack of diversity.

- Wildlife diversity — if you replace all the trees in a forest, you don’t "preserve" habitats for wildlife; you fundamentally alter them. As far as current wildlife is concerned, this spells destruction. That’s not to say that at some point these new forests couldn’t support a revised version of the previous biodiversity, but that would happen in the long run, not the short run.

- Cost — do you know how many trees Dyson wants to replace? About one third of the Earth’s land area is forest. One quarter of that, per Dyson’s suggestion, is about 1.25 billion hectares (or about 12.5 million square kilometers). Typical forest density is between 100 and 800 stems per hectare. Thus, Dyson proposes to replace between 125 billion and 1 trillion trees. To replant at high density (say about 700 trees per hectare) would cost about $500 per hectare, or $600 billion globally for a monoculture. Now that’s just to pay for the (genetically UNmodified) trees. And don’t forget that we won’t be planting a monoculture, according to Dyson, but mixed stands, which adds much more to the cost. And don’t forget all the roads we’ll have to build to remove 1/4 of the world’s forests and replace them with new ones. Or the laboratory costs of generating that many genetically modified tree clones. Silly stuff.

Totally unpractical.

Look, I’m all for technological solutions. I’m a plant biologist — I work on trying to engineer to plants to reallocate their resources better for biofuels production. But Dyson is WAY out of his element here. In fact, whenever he talks about biology (except in regard to the origin of life problem), he’s completely off the reservation.

I suggest RealClimate for another take.

Why Is Joe Klein Angry?

My old friend is hopping mad these days, and I have to say it looks good on him. I read the most recent to-and-fro while I was on vacation and have a few thoughts. The first is that Joe may well have supported the Iraq war reluctantly on Tim Russert’s show five years ago, as Pete Wehner will not let him forget. But I remember the period in question quite well and recall very vividly Joe’s prescient and passionate worries about the war – in particular a dinner we had in Provincetown around this time five years ago when he took me to task for my then-optimism and enthusiasm for the project. Like all of us, he has been buffeted this way and that by events in Mesopotamia, but using his intellectual honesty as a bludgeon against him strikes me as cheap. Joe is a patriot incensed by the glibness and callowness of so many Bushies who appear as indifferent to the immense costs of their war as to their own moral responsibility for its failures. I share his frustration and anger. Reading Charles Krauthammer accusing someone else of arrogance is really quite something.

But the latest attack on Joe is about Israel. Was this war in Iraq, in the minds of Kristol, Krauthammer, Kagan, Libby, Pohoretz et al, really, fundamentally about Israel’s interests rather than America’s?

I have no idea what’s in the recesses of all these people’s minds and hearts, and merely take them at their word (in a way they don’t with others, I might add) that their stated and open obsession with the Israel question does not imply any preference for Israel’s interests over America’s as such. But the real trouble with asking this question is that in the neocon mind, there is almost no area in which it is even possible to conceive of America’s interest being different from Israel’s. Moreover, for most of the past few years, the question has been largely moot. Disarming Saddam Hussein, for example, was obviously in everyone’s interests, Israel’s and America’s, and even his Sunni Arab neighbors’ and Iran’s. Trying to foster democracy in the Arab Middle East is likewise a good thing for any number of reasons, although not without short-term risks. It therefore never occurred to me that the debate over the Iraq liberation was a case for the divided loyalties question because the case stood or fell independently of any concern with Israel – and most smart Israelis actually opposed the Iraq war in any case as absurdly utopian.

The salient question, to my mind, is therefore: is there any point in future policy toward the Middle East that we can conceive of America’s interests not being identical with Israel’s and so set up a conflict with the neocons in which this unhappy squabble could be salient? I can see one imminent – the desire to occupy Iraq for the indefinite future and use it as a military base for regional and global power, as Krauthammer dreams of; and one looming – the prospect of a nuclear Iran. On the former, it’s striking how virulently a man like Lieberman wants to keep American troops policing the Muslim Middle East in perpetuity – especially given the brutal experiences of non-Muslim foreigners occupying the West Bank and Iraq. There are non-Israel-centric reasons for doing this, of course, but they are increasingly fragile when it comes to America’s national interest. Oil? Sure, but it was never that big a deal to the neocons, even though it looms large for the realists. So why on earth do we want to become a second Israel, occupying Muslim lands for ever? Israel may believe it has little choice on the West Bank. That does not apply to the US in Iraq.

On the Iran question, there can be little doubt that waging a pre-emptive war on the Persian regime is now the principal policy objective of the neocon right. To elect McCain is almost certainly to endorse a new war with Iran within the next four years. Again, this could be justified on the grounds of America’s interests and not Israel’s. But again, the case is getting a little harder to make. The world and the West can live, after all, with a deterred and contained nuclear Iran. Israel cannot. McCain and Lieberman hold the Podhoretz position on Iran; Obama is a few pragmatic notches away. Those notches – minor to most observers – nonetheless render Obama unacceptable to the Jewish right. Even after his AIPAC speech.

In some ways, that’s all you need to know. Israel is an issue that will emerge and emerge again as this potentially metastasizing war evolves in new ways. Given the stakes, this debate is not going away. One day we may thank Joe Klein for having the balls to jump-start it.

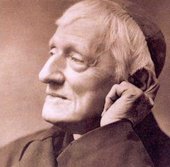

Face Of The Day

Exhuming Newman

For any English Catholic, the figure of Cardinal Newman looms large. An intellectual giant, a convert from Anglicanism, he is one of the greats – and now on his way to canonization. But Newman also had one great love in his life, Ambrose St John. When St John died in 1875, Newman wrote:

"I have ever thought no bereavement was equal to that of a husband’s or a wife’s, but I feel it difficult to believe that any can be greater, or any one’s sorrow greater, than mine."

Newman and St John lived together, loved one another and even left express wishes that they be buried together. And so they were, with the tombstone etched with these immortal and elliptical words:

"Out of shadows and phantasms into the Truth"

Whether this shared burial was a function of a deep intimacy or of a homosexual relationship in the late  nineteenth century sense we do not know. But we do know that the Oxford Movement was, to put mildly, high camp as well as high church, and that Newman, like the current Pontiff, was an effeminate, delicate intellectual who had almost no real interaction with women at all and bonded mainly with younger men. St John was one such man, and Newman’s and St John’s deepest wishes were to be buried together for ever.

nineteenth century sense we do not know. But we do know that the Oxford Movement was, to put mildly, high camp as well as high church, and that Newman, like the current Pontiff, was an effeminate, delicate intellectual who had almost no real interaction with women at all and bonded mainly with younger men. St John was one such man, and Newman’s and St John’s deepest wishes were to be buried together for ever.

Now, the Vatican, nervous that this joint burial might raise questions about Newman, and always eager to insist that gay men, even celibate ones, cannot be saints any more than they can now be seminarians, is actually exhuming Newman’s body and reburying it sans St John. Reburying saints is not unknown, but violating such a core last wish of this great man is definitely suspicious. They could exhume St John too and re-bury both together, respecting their clear wishes, but that would be off-message for the now pathologically homophobic Vatican.

Benedict does, however, have the wit of a gay man of the old school. When pressed a year ago by Cherie Blair to hurry up Newman’s canonization, Benedict apparently lamented that the church needed one more miracle to be attributed to Newman for it to proceed. "It is taking some time" his Holiness told Blair. "Miracles are hard to come by in Britain."

The Anthrax Question

John Judis wants a Congressional investigation into the source of the rumors that the anthrax attacks in 2001 originated in Iraq.

Will Obama Keep Gates?

It seems even likelier now.

Greenwald On Anthrax

A must-read. Glenn reminds me that it was the anthrax attacks that took the post-9/11 sense of threat to a whole new level – and moved the Iraq invasion forward as a possible response. That we now think the threat was actually a domestic source with no connection with Islamism is a critical piece of historical adjustment. The case is not definitively made, of course. But it’s very striking.

The central question of the time – how much danger are we actually in? – becomes harder and harder to discern. With torture as the Bush administration’s core weapon in the war on terror, we will now probably never know anything for sure.

A “Miraculous Fortnight”

Dean Barnett has some kind words for this blog (thanks, Dean) but thinks I’m delusional in saying Obama had an "objectively miraculous" fortnight. Of course, I did not mean by this that he wrapped up the election or that the pundit class swooned or the public was enraptured. In fact, Obama’s been treading water in the polls, in so far as they tell us much at the beginning of August. What I meant is simply that it’s remarkable that a first-term senator’s proposals on Iraq, having been decried as defeat and surrender by McCain and Bush, came to be endorsed by the Iraqi "government," and that McCain and Bush had to adjust their own views accordingly. It’s rare that any American politician who is not president would bring hundreds of thousands of foreigners into the streets of Berlin. It’s rare that a Democratic nominee would be endorsed by the most successful young right-of-center politician in Britain, and be hailed by the conservative president of France. It’s rare that such a newbie could pull off a complicated and pitfall-laden foreign tour without any noticeable gaffes or blunders. McCain is attacking Obama as a celebrity because Obama gave him no opening to attack him as an incompetent or unready on the world stage.

The fundamentals of the Obama campaign remain impressive to me. I have a feeling they will endure, even when the McCain camp sustains some tactical victories. In the end, this election will be decided on the core issues. On these, Obama still retains a serious advantage.

Super Trees

Freeman Dyson’s recent essay in the New York Review was the most helpful single piece on climate change I’ve read in weeks. He’s not as dogmatic as some climate worriers and persuasive, I’d say, in arguing that only technology can solve this problem (and government may not help much). But the possibility of genetically-modified carbon-eating trees is what really struck home:

Carbon-eating trees could convert most of the carbon that they absorb from the atmosphere into some chemically stable form and bury it underground. Or they could convert the carbon into liquid fuels and other useful chemicals. Biotechnology is enormously powerful, capable of burying or transforming any molecule of carbon dioxide that comes into its grasp. Keeling’s wiggles prove that a big fraction of the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere comes within the grasp of biotechnology every decade. If one quarter of the world’s forests were replanted with carbon-eating varieties of the same species, the forests would be preserved as ecological resources and as habitats for wildlife, and the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere would be reduced by half in about fifty years.

Climate change is, at its root, a scientifically-diagnosed problem that will be solved by science, not politics. Yes, politics can nudge the process along. But it’s not a politically-resolvable question. Which is why it’s still possible to be optimistic.