by Conor Clarke

If you're wondering what Sarah Palin will do after leaving the Alaska governor's office, look no further than her op-ed in the this morning's Washington Post. She writes, "at risk of disappointing the chattering class, let me make clear what is foremost on my mind and where my focus will be: I am deeply concerned about President Obama's cap-and-trade energy plan, and I believe it is an enormous threat to our economy."

As a card-carrying member of the chattering class, let me say that I am in indeed disappointed by this development. Not because Palin is showing a greater interest in policy, or because she'll be focusing on an issue that's near and dear to my heart. I'm disappointed because Palin's op-ed displays an ignorance for the subject so profound it's almost gutsy. Almost. Let's start with the big problem:

There is no denying that as the world becomes more industrialized, we need to reform our energy policy and become less dependent on foreign energy sources. But the answer doesn't lie in making energy scarcer and more expensive! Those who understand the issue know we can meet our energy needs and environmental challenges without destroying America's economy.

I don't think cap and trade has many supporters who think it's the best way to become "less dependent on foreign energy sources." (As a sidenote, I'd add that I'm skeptical we should become "less dependent on foreign energy sources" at all, for the same reason I'd be skeptical of becoming less dependent on foreign cars or foreign cucumbers. A "more industrialized" world is an accomplishment of free trade, not a reason to turn against it.) The point of cap and trade is to solve a problem of social cost: As an energy consumer, I am imposing a cost on society (pollution) that I do not take into account when I make the original decision to consume.

This happens all the time. My decision to drive creates traffic that imposes a cost on society. A company's decision to fish in the ocean imposes a cost on the world's common stock of fisheries. A banker's decision to take on a huge amount of risk creates danger for the economy as a whole. The problem is that none of these private actors adequately bears the cost of their decisions. So, the usual solution is to increase the price of these decisions — with congestion charges, or private property rights, or taxes — so that private consumers take into account social costs.

Still, in the case of pollution, there's no denying that a price mechanism will make life more difficult for consumers and energy producers, at least in the medium run. But let's treat this cost honestly! For example, Palin writes:

Job losses are so certain under this new cap-and-tax plan that it includes a provision accommodating newly unemployed workers from the resulting dried-up energy sector, to the tune of $4.2 billion over eight years. So much for creating jobs.

A quick note about the psychology of large numbers: $4.2 billion over eight years is $525 million a year. (That yearly cost is just above the total cost of, I dunno, building a road that

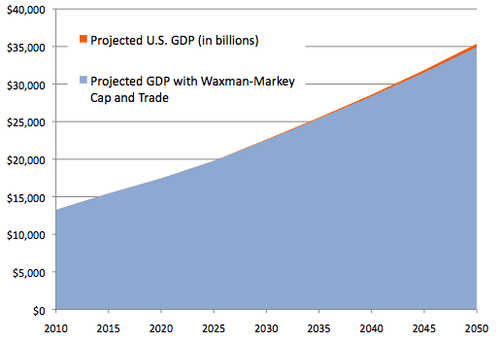

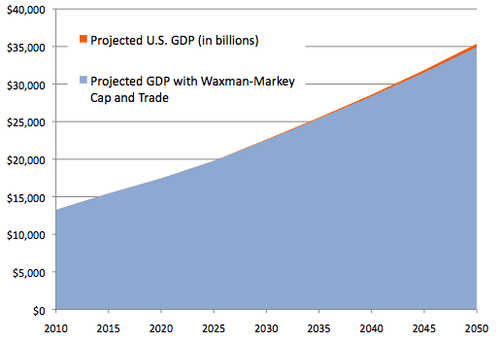

America will remain an incredibly prosperous nation with a cap and trade bill. Indeed, America will be a nation several times more prosperous than it is now! I think this is a small price to pay. Why doesn't Sarah Palin?