by Jim Manzi

Three academics claim to have a preliminary answer with the provenance of empirical science. William H. Dow, Arindrajit Dube and Carrie Hoverman Colla recently had an editorial in the New York Times arguing that San Francisco’s “near universal health care program” initiated early last year has not contributed to reduced employment despite the fact that “many businesses there had to raise their health spending substantially to meet the new requirements.”

How do they know the impact of this regulation on employment in San Francisco, when so many factors influence employment? They obviously can’t just look at whether employment went up or down after the law was passed. They need to answer the question: “But for the introduction of this regulation, what would employment have been?” The way they do this is identify a control group of other localities that did not introduce this change, and use this to proxy for what the change in employment in San Francisco would have been but for the introduction of this regulation. In the editorial they say “the early results are in”, and:

As of December 2008, there was no indication that San Francisco’s employment grew more slowly after the enactment of the employer-spending requirement than did employment in surrounding areas in San Mateo and Alameda counties. If anything, employment trends were slightly better in San Francisco.

There are at least two huge problems with concluding from this statement that the results so far in San Francisco tell us anything useful about the impact of such laws on employment. First, a period of just less than 12 months is almost certainly not enough time to observe the effects of the labor force impacts. Second, even if we accept this time period as relevant, the measurement method they describe is not nearly sufficient to identify significant changes in employment, positive or negative, caused by this law. Inadequate Time Period

Normally when the price of labor to a business goes up, the reaction of the business is some combination of (1) figuring out how to use less labor, and (2) just passing on the cost increase to consumers. If the business thinks all competitors face the same price increase, it tends to be a lot more of latter. Even when this is the case, the price of the whole category (whatever is sold by the business and all its competitors, whether this is an industry, geography or some other grouping) is now more expensive versus other categories of goods, so it tends to suffer over time as compared to what its sales and profits would have been had there been no labor price increase. This will tend to depress employment for companies in that category over time – often in the form of new jobs that otherwise would have been created, but now are not. Further, this category-level price increase tends to invite the entry of new competitors who can find a way around the labor costs. An obvious example of this set of dynamics is that the ever-increasing economic costs of labor to the Detroit ecosystem created by synchronized union contracts seemed OK for a long time because “everybody” (i.e., GM, Ford and Chrysler) faced the same costs. Eventually, they became obviously unsustainable because of external competition. In sum, the employment effects of a structural increase in labor costs can take a long time to play through.

The authors argue, somewhat unpersuasively, that San Francisco, like Detroit decades ago, can raise labor costs with impunity:

Local service businesses can … raise prices without risking their competitive position, since their competitors will be required to take similar measures.

But of course, this assumes that these service businesses are not in competition, over time, with businesses outside of San Francisco. To some extent, they are.

They also make the argument that the improved health care should create an offsetting benefit. This isn’t like an oil price shock, which is just all bad, but a reallocation of resources that could grow the whole pie of wealth for San Francisco. The authors put this as:

Over the longer term, if more widespread coverage allows people to choose jobs based on their skills and not out of fear of losing health insurance from one specific employer, increased productivity will help pay for some of the costs of the mandate.

Fair enough.

But think about the various dynamics involved. Labor costs rise in early 2008, and as a result prices are increased to some extent, and profit margins go down to some extent. Some restaurants lay people off, and other businesses are more reluctant to hire. As an example, last May the President of a local chain of hardware stores described avoiding hiring in order to remain below the 100-employee threshold for a more onerous tier of the program. Some people in San Francisco and the surrounding suburbs note prices are higher for dinner (and hammers, and groceries, and …) in the city, and start to buy marginally more goods and services in nearby towns, further pressuring margins and employment in San Francisco. Entrepreneurs, on the margin, locate businesses in Hayward or other towns just outside San Francisco, and as these businesses grow, the jobs that would have been created in San Francisco are now created in the suburbs. “Over the longer term” some career switches occur that otherwise would not, potentially raising labor productivity, growing the economy and increasing employment. How likely is all of this to play out in less than 12 months?

In light of such obvious issues, it is exceedingly odd that the authors have published an editorial in August of 2009 that relies on the results of the San Francisco policy “as of December 2008”. They’re throwing away at least six months of data (Q1 and Q2 of 2009). This is about one-third of all the time since the law was implemented, and given the reaction time involved, almost certainly more than one-third of all the information about what has happened as a result. More on this later.

Inadequate Test and Control Matching

But there is a further, and more severe, problem with the reasoning presented by the authors. Even if we look at the effects just within 2008, Alameda and San Mateo counties do not provide a sufficiently good control population for San Francisco to draw the conclusions that they assert.

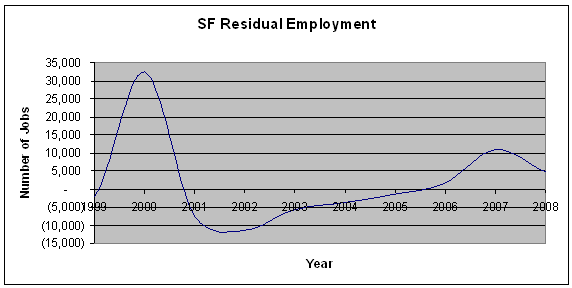

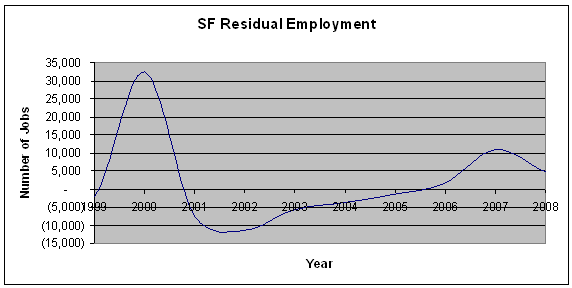

We can examine the usefulness of this proposed control group by looking at how closely annual changes employment in Alameda and San Mateo counties (“Control”) track San Francisco (SF). I’ve taken the total Control percentage growth in employment from year X to year X+1, and applied this percentage change to SF’s employment in year X to create “expected” employment in SF in year X+1 (i.e., what employment would have been in San Francisco in year X+1 had Alameda and San Mateo formed a perfect control). I then compare the actual change in the number of jobs in year X+1 in SF to this expectation, and call this the “residual” for that year. If the residual is positive, therefore, it means that SF gained more jobs in that year than would be expected based on the Control; if negative, the reverse.

Here is what this calculation looks like for about the last decade:

Hopefully, stating the residual in terms of number of jobs helps to make this intuitive. San Francisco has total employment of about 425,000. So, as an example, a swing of about 4,000 jobs represents a 1% change in employment. I think it’s fair to characterize such a causal impact as “significant”, in that on a national basis it would translate to an increase in the U.S. structural unemployment rate of about a percentage point (or the equivalent number of jobs lost through some combination of an increase in the unemployment rate and a reduction in the number of people looking for work). How likely is it that this instrument could find a causal effect of 4,000 jobs?

Asked more rigorously, what are the odds that the ~5,000 job gain in SF vs. Control in 2008 (“If anything, employment trends were slightly better in San Francisco.”) is simply statistical noise? Here’s a simple but useful way to think about it. If the SF health program had the causal effect of significantly reducing employment by, say, 1 percent, this would mean that but for the SF health program, SF would have had a residual of 9,000 jobs in 2008 (the 5,000 actual residual + the extra 4,000 jobs that would have been there but for the health program). SF has shown a residual at least this high in two of the past ten years (2000 and 2007), or 20% of the cases. (And even this understates our real uncertainty, since we don’t know that the distribution of control error that we have seen over the prior decade is representative of differences between SF and Control in 2008). Conventionally, we would not reject the null hypothesis that this could be random variation unless there is less than a 5% chance of this occurring.

If you think this is quibbling, ask yourself this question: had the authors conducted this analysis in 2002, do you think they would publish a study, and the New York Times would run an editorial, saying that “The early results are in, and universal health care seems to be a job killer.”? And if they (or more likely, if a paper more hostile to universal health care had), they would have been wrong, as we know that the 10,000+ downward swing in San Francisco versus Alameda and San Mateo counties in 2002 had nothing to do with a program that would not be implemented for six more years.

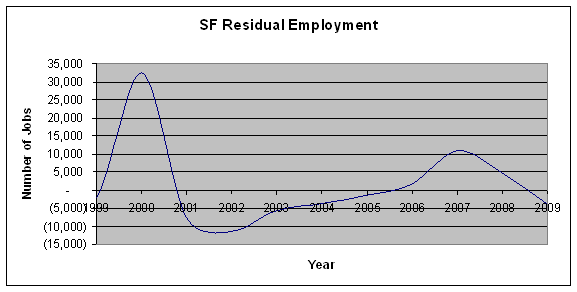

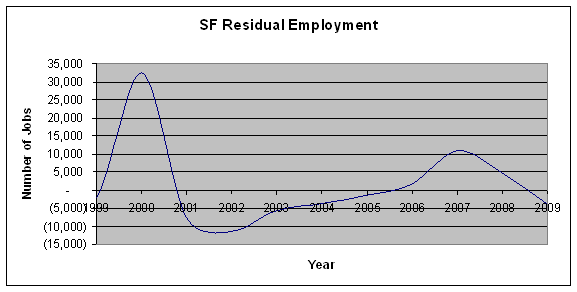

Or consider that if we take the residual through the first half of 2009 and simply annualize it, we get a chart looks like this:

It would be very easy for me to “construct a narrative” that we now see the longer-term negative impacts of this program emerging: “Look, the employment in San Francisco stopped its upward trend versus Alameda and San Mateo counties right when this program was implemented, and has now started a precipitous decline!”. Or whatever. But this would be, like the editorial, a just-so story. The relative employment performance of San Francisco versus two nearby counties over about 18 months is not an instrument with sufficient precision to identify the even quite significant potential causal impacts of this program on employment.

As far as I can see, there is no published paper that would allow an external observer to evaluate the work behind claims in the editorial more completely, just an unpublished work-in progress not available for download (though obviously there may be some way to get it that I haven’t found). It’s possible, for example, that the authors have carved out a clever subset of geographies within the Alameda and San Mateo counties to use as controls, or have used regression-like techniques to further adjust the residuals. Each of these methods has its own problems. In any event, the stated demonstration in the editorial does not seem to hold water.

Interestingly, one of the authors (Dube), has previously published a methodologically sophisticated academic paper in which he argued that when doing exactly this kind of analysis that compares contiguous counties that straddle a political jurisdiction in order to estimate the employment effects of a policy discontinuity (in the case of the paper mentioned, to evaluate the impacts of increases in the minimum wage on employment). One of his methodological conclusions was that such individual “case study” comparisons as that of SF to Alameda and San Mateo counties are fraught with danger:

As we show in this paper, the odds of obtaining a large positive or negative elasticity from a single case study is non-trivial. This result establishes the importance of pooling across individual case studies to obtain more reliable inference, a point made in earlier papers.

(As an aside, in this paper Dube uses the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, which permits industry-level analysis, as his primary data set for employment outcomes. This data is only produced by the government with a six or seven month lag. I assume that he is employing a very similar method for the analysis behind the San Francisco health care editorial, and that this is what accounts for only using data through the end of 2008.)

I am an aggressive proponent of using experiments to obtain valid inferences about the effects of public policies. What this example makes clear, however, is the importance of either very careful experimental design, or in the case of so-called “natural experiments”, extreme caution about methods of interpretation. In this case, the argument made by the authors in one of the most prominent pieces of real estate in American public debate appears to be insufficient to support their conclusion.