by Jim Manzi

I’ve said in previous posts on other blogs that one of the great features of The Daily Dish is it encourages active disputation, which I seem to be getting on my posts – good and hard. Patrick Appel has posted reactions to my post on the social cost of carbon. The comments are excellent, and I’ll try to address them one at a time. Commenter 1 starts with:

For one thing, Manzi brushes the entirity of "social cost of carbon" into the potential decline in world economic product (a loss of approximately 3%). This not only excludes costs which I would deem "social" such as habitat and species loss, land degradation, and changes in local climate, but also aggregates the risk into a global pool, which is assuredly too crude a measure to make a meaningful judgment. To take the extreme case, what if the 3% loss were entirely distributed in 6% of the world's population losing half their economic productivity? The 3% measure looks small on paper, but in this instance 180 million people (over half the population of the US) just had their livelihoods utterly destroyed, to the point that they are now refugees. While this extreme concentration of risk is certainly fiction, it is patently clear to both the casual reader and the sophisticated analyst that the costs of climate change will not be equally distributed. The risks to the majority of the 160 million in Bangladesh should be enough to invalidate such crude aggregation of costs.

This is very similar to a question that an interviewer at The Economist asked me last week. Here’s my short reply:

It is true that low-lying, poor equatorial regions are expected to suffer disproportionately from AGW, but on the other hand, these regions would also expect to suffer disproportionately from any reduction in economic growth that would be caused by programmes to reduce CO2 emissions. For exactly this reason, average GDP per capita in the developing world, along with the health and other quality-of-life indicators that are highly correlated with income for such poor areas, are all expected to be higher at the end of this century in a world with a carbon-intensive path of economic development than it would be in an alternative world with slower growth, but lower CO2 emissions.

You can see a much more detailed reply to the ethical question this commenter poses here. A much more detailed reply concerning the material (money and otherwise) impacts of various development approaches that emphasize economic growth versus emissions mitigation is here. Commenter 1 continues with:

For another, in his association of all British driving taxes with "anthropogenic global warming (AGW)," he elides the myriad other costs of driving, including public health, land use, public land preservation, safety and enforcement, etc. Yes, once again these costs are difficult to quantify. This, however, does not mean they do not exist.

After dozens of paragraphs of analytical spinning, Manzi reaches the third to last, and engages in a breathtaking series of theoretical leaps. Costs are impossible to quantify, therefore "It becomes pure power politics," and therefore is a state imposition of economic costs without quantitative justification, and is therefore akin to total state planning of the economy. Excuse me, but WHAT?!?

To put this as simply as I can, there is a vast universe between "inability to sufficiently quantify" and "a different theoretical justification [for socialism]." What Manzi is experiencing is not the unearthing of socialist motives, but the limits of the quantitative revolution of the 20th century. There was a time, as strict Enlightenment rationalism and to a lesser extent, positivism reached their zenith, that we supposed that all complex issues could be solved with sufficient quantitative analysis. Difficult questions such as the costs of action or inaction on climate change demonstrate this as well as anything, but the lesson to take here is not that we have no analytical tools at all and retreat to pristine ideological tropes. (In this, I think Manzi is unintentionally making what I might call the Bachmann move — it's impossible to quantify, and it involves government action, therefore it is the first step towards tyranny.) Rather, it should be a clarion call to dust off analytical methods tossed aside during much of the quantitative revolution, such as informal logic, deep description, dialectics, rigorous observation, ethics, and comparative studies. (One can even retain critical rationalism, just without getting lost in numbers.)

In several places, I made it clear that I was not making the “Bachman move” (which is a great name, by the way), both by preemptively mocking it as what could be called the “Animal House move”, and then in the summation explicitly saying that:

I yield to few men in my admiration for Hayek and his ideas. His prediction that the welfare state would lead to serfdom, however, has (thus far) not been correct. I don’t think that a carbon tax will be the one event that will push the free world into socialist slavery.

The really interesting part of this commenter’s criticism, to me at least, is his attack on the “quantitative revolution of the 20th century” and the idea that “all complex issues could be solved with sufficient quantitative analysis”. As far as I can see, this is exactly what I was also attacking in this post. It seems to me that this is very much like an updated special case of the socialist calculation debate, and I am arguing against calculability. Commenter 2 says:

There are usually many reasons to do something, and arguably there are more important reasons to tax carbon, and especially gasoline. Here are two off the top of my head: Decreasing our dependence on imported oil would make the Mideast a heck of a smaller powder keg. And since oil is a finite resource, it makes sense to conserve it if there are viable alternatives available. More electric cars and nuclear power plants, for example, would address these issues as well as those associated with AGW, and why not pay for it (in part) with a tax on gas?

Fair enough. There are lots of unquantifiable reasons to do lots of important things in life. But I was attacking a very specific argument: that we should tax carbon because we know that it will impose AGW-related costs. Here is the opening of my post:

Burning fossil fuels creates so-called “external costs” because it contributes to ongoing climate change. This is a fancy way of saying that when I burn such fuels, other people become worse off than they would be otherwise, because I have increased the odds that they will suffer damages from anthropogenic global warming (AGW). This both seems unfair, and means that we will burn more fossil fuels than would seem to be socially optimal. It seems obvious to many people that we should therefore tax fossil fuels in order to prevent this. This is termed a Pigovian tax, and is sometimes referred to as “internalizing the externality”, or taxing fossil fuels to reflect the “social cost of carbon”.

It’s not so obvious to me that this is good idea. To implement it would be little more than a re-labeling of the kind of comprehensive planning that Hayek attacked sixty years ago. Here’s why.

The entire post is not an argument against carbon taxes per se, but instead an argument against the idea that carbon taxes can be rationally based on our beliefs about AGW damages.Commenter 3 starts with:

Your argument has several fundamental empirical flaws and at least a few fallacies. First, your assertion that the IPCC's report provides a probability distribution that suggests at most a 3% decline in world GDP based on the most likely scenario is technically accurate, but ignores the data that has emerged since the report was written. In terms of ocean temperature increases, glacial and arctic sea ice melting, and total carbon released into the atmosphere, we've already exceeded the IPCC's most pessimistic trend forecast (remember, their trend forecasts were actually based on the belief that states would at least attempt to abide by the Kyoto Protocol). Updated modeling has placed so-called "tipping point" thresholds, which would result in substantial economic losses, to within 50 to 75 years rather than 100 to 150. In other words, the IPCC's existing probability distributions for "worst case scenarios" are already outdated.

Since the IPCC's report, new evidence has come to light of biological and climactic processes that make it even more likely that a worst-case scenario might emerge before the end of this century. This includes research on ocean acidification, the role of latent methane found in the slowly thawing subarctic tundra and deep within the ocean, and the masking effect of particulate pollution, which, once removed, will drastically increase ocean temperatures. You may be unaware of this research, but all signs seem to point to the unfortunate conclusion that the IPCC report was far too conservative.

I’ve done enough science, in areas totally unrelated to AGW, to be confident that I’m not competent to read, understand and integrate numerous scientific papers on this very broad topic. No individual is, in my opinion. That’s the whole point of the IPCC process of creating Assessment Reports. If it were possible for somebody to just read the papers and update our estimates, there would be no point to assembling these thousands of scientists and doing all of this laborious work to create these reports. I have always relied on the IPCC process for the best available answers to technical questions. Commenter 3 continues:

This is all important because your argument rests on an assumption that the risk is not high enough based on the available evidence to warrant internalizing the costs of producing carbon. We now know that the risk appears to be rising, along with the potential costs if the problem is left unaddressed. Unlike congestion or noise, where costs are both well-known and hold a linear relationship with policies meant to address them. The costs of accumulating CO2 in the atmosphere are simply not well known and even the best economic models are mere guesses at the actual cost (primarily because, as you rightly point out, the problem involves so many potential counterfactuals). There's a very real possibility that the costs might be so high some time in the near future that eventually any expense will be justified, including your doomsday scenario where we all collectively turn off our cars and shutter the power plants. What we do know is that there is a substantial lag between the release of CO2 and its effect on Earth's climate, which means if we wait to see whether the cost will really materialize we will probably have waited too long to prevent costs from rising exponentially. Thus we may be facing the choice of a small investment now to slow the process versus a very large investment in the future to mitigate its effects.

This is a clear rational basis for belief in inherently unquantifiable uncertainty, rather than mere quantifiable risk, in our projections for future AGW damages. This can be used to justify carbon taxes, but as I said in the post:

The only real argument for rapid, aggressive emissions abatement boils down to the point that you can’t prove a negative. If it turns out that even the outer edge of the probability distribution of our predictions for global-warming impacts is enormously conservative, and disaster looms if we don't change our ways radically and this instant, then we really should start shutting down power plants and confiscating cars tomorrow morning. We have no good evidence that such a disaster scenario is imminent, but nobody can conceivably prove it to be impossible. Once you get past the table-pounding, any rationale for rapid emissions abatement that confronts the facts in evidence is really a more or less sophisticated restatement of the precautionary principle: the somewhat grandiosely named idea that the downside possibilities are so bad that we should pay almost any price to avoid almost any chance of their occurrence.

But if you want to use this rationale to justify large economic costs, what non-arbitrary stopping condition will you choose for how much we should limit emissions? Assume for the moment that we could have a perfectly implemented global carbon tax. If we introduced a tax high enough to keep atmospheric carbon concentration to no more than 1.5x its current level (assuming we could get the whole world to go along), we would expect to spend about $17 trillion more than the benefits that we would achieve in the expected case. That’s a heck of an insurance premium for an event so low-probability that it is literally outside of a probability distribution. Of course, I can find scientists who say that level of atmospheric carbon dioxide is too dangerous. Al Gore has a more aggressive proposal that if implemented through an optimal carbon tax (again, assuming we can get the whole word to go along) would cost more like $23 trillion in excess of benefits in the expected case. Of course, this wouldn't eliminate all uncertainty, and I can find scientists who say we need to reduce emissions even faster. Once we leave the world of odds and handicapping and enter the world of the precautionary principle, there is really no principled stopping point. We would be chasing an endlessly receding horizon of zero risk.

The most rigorous version of the argument for carbon taxes based on this uncertainty (and, in my opinion, the best existing case of any kind for a carbon tax) is by Harvard economics professor Martin Weitzman. You can read my detailed, and fairly technical, reply here.Commenter 3 goes on to say:

Your attempt to belittle the carbon tax as ineffective is a bit disingenuous since your real argument is that no effort on the part of the U.S. government justifies the cost of abating what you see as a relatively minor problem that has a very very low probability of becoming catastrophic.

I hope I’ve been very clear about my opposition to coercive emissions mitigation predicated on avoiding AGW costs. He continues:

Thankfully, that's a position that can be proven or disproven over time as we start to see the actual effects of climate change.

I mostly agree, subject to the qualification that no probabilistic prediction is ever strictly falsifiable. Finally commenter 3 ends with:

As for your view on taxes and socialism, I respect Hayek's argument and the potential that such a tax, implemented poorly or set too high, could lead to a loss of individual freedom, but I'm unaware of any system of government that has provided for the public welfare without a tax, and I do believe that ameliorating the effects of climate change provides a substantial benefit to public welfare, so on this we'll have to disagree.

The alternative theory of taxation is that, broadly speaking, we should use them to collect revenue in the manner that appears to have the smallest distortionary effect on behavior, rather than use them to create a “double dividend” a la Pigou, because our attempts to manage behavior in this way usually backfire. Commenter 4 says:

Mr. Manzi wrote “In order to set the tax, we don’t just need to know the costs created by [anthropogenic global warming]… but rather all of the social costs and benefits created by the activity, which is far harder.” This is just a mistake. Unless the market is generally defective, prices should naturally incorporate these costs and benefits.

I don’t think so. He then continues:

It is because there’s a sort of point defect – the market’s inability to price in carbon externalities – that we discuss carbon taxes or whatever. It’s true that determining the actual degree of the externality is controversial and can plausibly be argued to be intractable, but correcting for an externality does not require calculating all downstream effects, and it is that asseveration in Manzi’s post that imports “socialism” into the discussion.

Why is AGW cost a “point defect”? My point in building out in “concentric circles” from AGW externalities, to other negative externalities of burning fossil fuels, to positive externalities, to externalities from other energy sources, to all externalities, was that there is nothing magical about AGW. What we care about are the costs (people die, economic growth suffers, etc.). In order to argue that out of all these nearly infinite number of externalities that we should tax carbon, I think that one has to argue something like either: (1) AGW has such a huge costs, that as a practical matter we should focus on it instead of just about everything else; or (2) that we should be charging taxes (positive or negative) on lots and lots and lots of activities. I was then trying to show that (1) is factually incorrect, and that (2) either leads to tyranny if implemented seriously, or (much more likely) is used as a rhetorical tool by political elites to seize resources and power.Commenter 5 begins:

Manzi writes: "According to the authoritative U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), under a reasonable set of assumptions for global economic and population growth, the world should expect (Table SPM.3) to warm by about 2.8°C over the next century. Also according to the IPCC (page 17), a global increase in temperature of 4°C should cause the world to lose about 3 percent of its economic output. So if we do not take measures to ameliorate global warming, the world should expect to be about 3 percent poorer sometime in the 22nd century than it otherwise would be." – Economics is a system created by humans, and it measures only a very limited part of human life: Productivity. It's precisely a retreat into the economic that allows people to dismiss concerns over things like climate change. Since the Industrial Revolution we have been engaged in a relentless search for 'efficiency', the maximization of productivity and profits at any cost, and it's gotten us a long way. But we are now seeing its limits. How many 'units of social cost' is the existence of polar bears worth? It's not worth any percentage points of productivity on an economic scale, but polar bears (and clean, fresh air, and beautiful natural places, and all the rest of it) sure do seem important.

At least for the next century, most global measures of quality-of-life (human health, environmental stresses and so forth) are projected to be better under a regime of rapid economic growth, even with the damages of CO2 emissions, than a regime which coercively restricts emissions at the expense of some economic growth. This is disproportionately driven, by the way, by the developing world, because the marginal benefits of increased wealth in creating these positive life conditions are so much higher there.However, my “at least for the next century” qualifier opens up what I agree with commenter 5 is his most important point:

Following off the same quote I pulled, I'd like to make what I consider my most important point. It's a question, a question that I've never really seen asked properly and that I'd love to hear Manzi's answer to: How long are we trying to keep this humanity thing going? He points to the statistic that temperature will rise less than 5 degrees in the next century, and says that means something as if that were the upper boundary of life on earth. Even in terms of human civilization (forgetting geologic time) a hundred years is not very long. So say in a century the earth is 4 degrees hotter, then what? We care about our children and grandchildren, but screw THEIR children and grandchildren? Is that really the attitude that Manzi is suggesting we adopt? We may not get very far down the path towards an uninhabitable earth in the next 100 years, but we're still on that road. Isn't that automatically an emergency?

I’ll start my reply with the obvious observation that somewhere between 385 parts-per-million of CO2 in the atmosphere and 1 million parts-per-million, we can be pretty confident that the planet would all but uninhabitable. So at some point, humanity will either have to reduce emissions, scrub CO2 out of the atmosphere or find some other currently unanticipated solution. In the absolute extreme, then, the current course of economic development is unsustainable. But this doesn’t, in my view, mean that the right course of action is therefore to intervene coercively right now. Why not?

If we had reasonable scientific knowledge that we could foresee a catastrophe within any reliable forecast period, we should act on that. But we don’t, as per my posts. If we could even handicap reasonable low but non-trivial odds that something like this would happen, we should act on that. But we don’t have that either. We have only the fear even our handicapping underestimates the danger. (And let me emphasize that I think this is a rational fear – our ability to predict the climate developments, never mind the human impacts is, to put it mildly, not exact)

But there’s a huge problem with therefore sacrificing a significant fraction of the world’s resources – say 2% or 3% of global economic output – to insure against this danger. This would be myopic about risk. We face lots of other unquantifiable threats of at least comparable realism and severity. A regional nuclear war in central Asia, a global pandemic triggered by a modified version of the HIV virus, or a rogue state weaponizing genetic-engineering technology all come immediately to mind. Any of these could kill hundreds of millions of people. Specialists often worry about the existential risks of new technologies spinning out of control. Biosphere-consuming nano-technology, supercomputers that can replace humans, and Frankenstein-like organisms created by genetic engineering are all topics of intense speculation. Sometimes, though, we face monsters from the deep: The cover of the June Atlantic Monthly said of the potential for a planet-killing asteroid, "The Sky Is Falling!"

To put a fine point on it, consider this case of asteroids: replace "global warming" with "planet-killing asteroid impact". Earth-impact asteroids are a non-imaginary threat, and there is already significant government expenditure devoted to this problem. They hold the potential to all but exterminate the human species. By the logic of your question, why would you not invest, say, 2% of global GDP per year into perpetuity (roughly equal to about $1 trillion, or the total annual collections from the US income tax), to develop and deploy an interdiction system for earth-impact asteroids? If not, how do you distinguish between your fear of climate change impacts beyond the consensus scientific forecast, and a fear of asteroids?

In short, while my stance may come off as Panglossian about our future, it’s really the opposite. A healthy society is constantly scanning the horizon for threats and developing contingency plans to meet them, but the loss of economic and technological development that would be required to eliminate all theorized climate change risk (or all risk from genetic and computational technologies or, for that matter, all risk from killer asteroids) would cripple our ability to deal with virtually every other foreseeable and unforeseeable risk, not to mention our ability to lead productive and interesting lives in the meantime.

In the face of massive uncertainty, hedging your bets and keeping your options open is almost always the right strategy. Money and technology are the raw materials for options. The idea of the simple, low-to-the-ground society as more resilient to threats is a resonant myth. But experience shows that wealthy, technologically sophisticated societies are much better able to withstand resource shortages, physical disasters, and almost every other challenge than poorer societies.

Consider that if a killer asteroid were actually to approach the Earth, we would likely rely on orbital telescopes, spacecraft, and thermonuclear bombs to avert disaster. In such a scenario, we would be very glad that we hadn't responded to prior threats of resource shortages by slowing our development to such an extent that we lacked one of these technologies. In the case of global warming, a much more appropriate approach than rationing energy and forgoing trillions of dollars of economic growth is to invest a fair number of billions of dollars into targeted scientific research that would give us technical alternatives if a worst-case scenario began to emerge.

We should be very cautious about implementing government programs that require us to slow economic growth and technological development in the near-term in return for the promise of avoiding inherently uncertain costs that are projected to appear only in the long-term. Such policies conceal hubris in a cloak of false humility. They inevitably demand that the government coerce individuals in the name of a nonfalsifiable prediction of a distant emergency. The problem, of course, is that we have a very bad track record of predicting the specific problems of the far future accurately.

We can be confident that humanity will face many difficulties in the upcoming several centuries, as it has in every century. We just don't know which ones they will be. This implies that the correct grand strategy for meeting them is to maximize total technical capabilities in the context of a market-oriented economy that can integrate highly unstructured information into prices that direct resources, and, most important, to maintain a democratic political culture that can face facts and respond to threats as they develop.

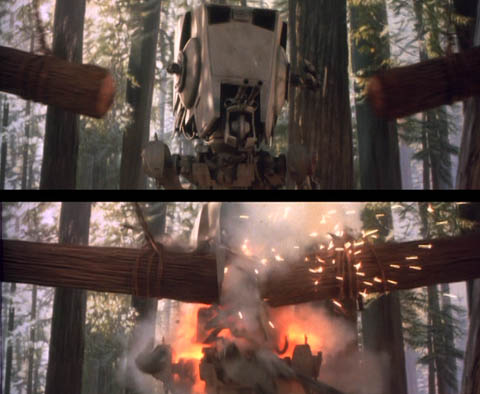

Empire and the Rebel Alliance, a classic insurgency is even possible? If one of the insurgent's biggest advantages is his knowledge of the local environment, and the tacit support of the inhabitants of that environment, then isn't that advantage pretty much negated in the vacuum of space? I imagine that the space-based nature of war in the Star Wars universe constrained the Alliance's strategic options, perhaps significantly. I suspect that the rebels were pursuing the best set of tactics available to them – waging asymmetric war against the Empire's vulnerable conventional military assets. […]

Empire and the Rebel Alliance, a classic insurgency is even possible? If one of the insurgent's biggest advantages is his knowledge of the local environment, and the tacit support of the inhabitants of that environment, then isn't that advantage pretty much negated in the vacuum of space? I imagine that the space-based nature of war in the Star Wars universe constrained the Alliance's strategic options, perhaps significantly. I suspect that the rebels were pursuing the best set of tactics available to them – waging asymmetric war against the Empire's vulnerable conventional military assets. […]