by Chris Bodenner

Pew has a quiz.

by Chris Bodenner

Pew has a quiz.

by Jonathan Bernstein

Yesterday's big electoral news was a rumor that Charlie Crist might really bolt and run a third-party campaign for the Senate. I posted yesterday about the implications for voting in the Senate during the remainder of the current Congress, but I agree with those who believe that these sorts of purist primary challenges are important to the future course of the Republican party. Here's Ezra Klein:

[I]t would be bad for Democrats — and I'd say for the country — if Crist simply loses to Marco Rubio in the Republican primary. The better conservatives get at mounting effective primary challenges against moderate Republicans, the more impossible it is for moderate Republicans serving in Congress to act like anything but hardline conservatives…The only way to stop that trend is to convince Republicans it's bad for them: New York's 23rd already went for a Democrat, and now if Specter leaves and wins, and Crist leaves and wins, that'll really discredit the effectiveness of the primary approach at electing conservative alternatives.

Two things. First, one of the possible outcomes here is for the Republicans to marginalize themselves so much that they become a clear minority party for a longish stretch of time. That's not bad for the Democrats!

Second, I think he's right that the main way to reverse this is to convince Republicans that it's electoral poison to nominate extremists (defined, by the way, just as candidates who support policies that are very popular among conservative Republicans but not popular among the rest of the electorate). For better or worse, however, I think it's implausible to believe that a Crist third-party win will convince anyone of anything. Republicans are extremely likely to wake up on November 3 this year with an election they perceive as a landslide; (even if they only win 2-4 seats in the Senate and 20 in the House they're going to think of it as a big win), and consequently they're likely to interpret everything that happened since the 2008 election as helpful. In fact, Republicans are likely to do well in the 2010 cycle just because the Democrats did so well the last two times (and therefore control lots of swing seats, while Republicans only have to defend seats that survived two good Democratic years), and because the out-party tends to do well in mid-term elections.

Let's say that Republicans pick up 35 House seats and six Senate seats, but that Crist does bolt, wins as an independent, and caucuses with the Democrats and votes like Joe Lieberman; let's also say that Republicans lose another Senate seat and five or so House seats that they could have won by nominating more moderate candidates. Conservative activists aren't going to look at those results and conclude that if only they had backed off on various challenges that Republicans might have done even better; they're going to look at those results and declare it a huge victory for conservatives, and reinforce their belief that conservative actions since 2008 — a rejectionist strategy in Congress, extreme rhetoric against the president on the talk shows and the blogs, and strong conservative candidates across the board — were electorally smart.

The larger lesson is that politicians, and political actors, tend to interpret political events based on their own biases and interests. Polling on health care right now is ambiguous, but conservatives are absolutely convinced that the Democratic health care reform bill is massively unpopular, while liberals are equally convinced that it's quite popular. So conservatives interpreted the 2008 election as a repudiation not of conservatism, but as a repudiation of Congressional and presidential deviations from conservatism (in fact, the 2008 election was more of a reaction to a deep recession than anything else — of course, that just moves the argument to whether liberal or conservative parties were responsible for the recession). It's not impossible for pols and activists to learn useful lessons, but the evidence is that they learn slowly and inefficiently.

Bottom line: yes, it is electorally bad for parties to nominate unelectable ideological candidates. No, Republicans aren't going to stop doing it even if it costs them seats in the 2010 election cycle.

by Chris Bodenner

Sam Sanders surveys a new Facebook phenomenon called "Farmville" – a game with more players than people on Twitter:

The average Farmville user is a 43-year-old woman. More women than men are "avid" users of social games like Farmville. Women are more likely to play these games online with their relatives and real-world friends than men. Two-thirds of these social gamers play at least once a day. One in four spend money playing them.

This new data challenges some preconceived notions about just who is actually playing games online. The image of the nerdy, male, mid-thirties recluse, playing shooting games over the internet with fellow nerdy, male, mid-thirties recluses on the other side of the world might be forever shattered.

Austin MacKenzie looks at the big picture:

"Facebook knocked us on our ass this year – we didn't see it coming," game design professor of Carnegie Mellon University Jesse Schell said. "Facebook is terrifying to the traditional games biz."

Schell said the success of Facebook games is due in no small part to the utilization of psychological tricks, where the games are initially free but unlocking special features costs money. Other games such as Mafia Wars, Schell said, have you directly compete against your friends and family. This competitive nature encourages people to play longer and invest more money to win.

Much like the advent of Guitar Hero and Wii Fit these new Facebook games totally blew traditional game developer expectations out of the water, Schell said. These new approaches to gaming could have a huge impact on how developers make games. Schell predicts the methods social networking sites like Facebook ingratiate themselves into a person's everyday life will become more prevalent with gaming as well.

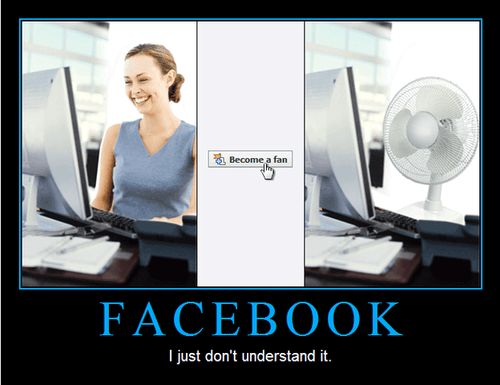

(Image via Laughing Squid)

by Patrick Appel

The 5-minute nap produced few benefits in comparison with the no-nap control. The 10-minute nap produced immediate improvements in all outcome measures (including sleep latency, subjective sleepiness, fatigue, vigor, and cognitive performance), with some of these benefits maintained for as long as 155 minutes. The 20- minute nap was associated with improvements emerging 35 minutes after napping and lasting up to 125 minutes after napping. The 30-minute nap produced a period of impaired alertness and performance immediately after napping, indicative of sleep inertia, followed by improvements lasting up to 155 minutes after the nap.

Science Fair bolsters the case for midday naps. The Atlantic's Ellie Smith advocated for naps at work awhile back.

by Patrick Appel

Stewart Brand sees the potential of urbanization:

Urban density allows half of humanity to live on 2.8 per cent of the land. Demographers expect developing countries to stabilise at 80 per cent urban, as nearly all developed countries have. On that basis, 80 per cent of humanity may live on 3 per cent of the land by 2050. Consider just the infrastructure efficiencies. According to a 2004 UN report: “The concentration of population and enterprises in urban areas greatly reduces the unit cost of piped water, sewers, drains, roads, electricity, garbage collection, transport, health care, and schools.” In the developed world, cities are green because they cut energy use; in the developing world, their greenness lies in how they take the pressure off rural waste.

by Graeme Wood

Gordon Sumner, better known as Sting, is cashing a two-million dollar check from the daughter of Uzbek dictator Islam Karimov, in exchange for performing at her arts festival. Marina Hyde has the story.

Craig Murray, the outspoken former UK ambassador to Uzbekistan, calls Sting's defense "absolute bollocks":

I agree with him that cultural isolation does not help. I am often asked about the morality of going to Uzbekistan, and I always answer – go, mix with ordinary people, tell them about other ways of life, avoid state owned establishments and official tours. What Sting did was the opposite. To invoke Unicef as a cover, sat next to a woman who has made hundreds of millions from state forced child labour in the cotton fields, is pretty sick.

Murray and others have alleged that Karimov has boiled his enemies alive.

A commenter suggested a boycott of Sting's music. I was going to agree, but on reflection it would take an enormous effort to track down someone who listens to it, before we could ask them to stop.

(Via Joshua Keating.)

by Chris Bodenner

ISO50 collects tips from dozens of designers and artists:

Set your bedside alarm for 5am. When it goes off either get up and enjoy the unique feel of that time of day or go back to sleep and have the craziest dreams (REM sleep is easier to reach/remember) – one of these experiences will give you inspiration.

Ocracoke, North Carolina, 10.17 am

by Jonathan Bernstein

First, I'd like to say hello to everyone, and to thank Andrew for asking me to stop by here while he's out. I'm a political scientist; as a group, we were late adapters to blogging, but it's becoming all the rage these days.

There are plenty of things that we, as political scientists don't know…but sometimes, we do have some useful information. For example, there's an annoying AP story this morning claiming that declining trust in government has something to do with…television. And yet, as political scientist Henry Farrell says, "When the economy is doing well, people trust government, they trust Congress and they trust a bunch of other institutions. When the economy's doing badly, people's faith tends to drop.'' Unfortunately, after the AP quotes Farrell, the story then ignores him and returns to speculation about how damaging it is for people to see things like the health care summit, with its bickering and lack of immediate action, on TV.

Well, not so. Political scientist John Sides did a nice item on trust recently at The Monkey Cage, showing that trust in government fell steadily in the 1960s and early 1970s (no surprise, given Vietnam and Watergate) and since then — in fact, since the mid-1960s — trust in government basically follows the economy. Contrary to the AP, loss of trust doesn't track with the rise of television (we don't really know because the data doesn't go back far enough, but trust was awful high in 1958, following the first decade of TV). Nor does it dip with the introduction of 24-hour coverage or the internet — in fact, trust rose in the 1980s, and in the late 1990s.

More important, I think, are the implications of falling trust. The AP worries that falling trust "could turn society's skepticism to debilitating cynicism." But trust in government was pretty low in 2008, and I think it's hard to characterize that election as one of debilitating cynicism. Trust was pretty low in 1992, and that was another high-turnout election. For better or worse, trust just doesn't seem to behave the way alarmists think it should.

So, I'll start my week here reassuring everyone: of all the things that you might want to worry about, I'd put levels of American trust in government near the bottom of the list. As John Sides says: "More people will trust the government again when times are good, even if government ain’t."

by Patrick Appel

Via Soup real-time video and images from Chile. Enduring America is live-blogging.