TNC wishes journalists were upfront about it:

[M]edia in general, often confuse accuracy with honesty. I think analysts, reporters, and the people overseeing them, are loath to admit error because they see it as a kind of brand erosion. The question becomes–If I admit to you that I was wrong, why should ever trust me to be right again? My sense is that only a fool actually expects media people to be right all of the time.

What they expect, I think, is for you to be honest and informed…

[Then] there's what my label-mate Andrew calls, "journalism's dirty secret." The dirty secret is this–perhaps more than any other "profession" journalism's barriers to entry are really artificial. It does take a special person to be a great journalist. Curiosity in the extreme is important. A strong desire to see, and thus think, clearly is important. But neither of these can really be taught in a crude classroom environment. Journalism can't be absorbed through a series of lectures and assigned readings. It must be done. No one can teach you how to go up to strangers and ask rude questions. You just have to do it. Repeatedly.

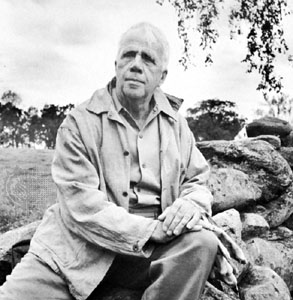

brings the two neighbors together. Frost is tricky because we tend to read his invocations of nature romantically. "Something there is that doesn't love a wall/ That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it,/ And spills the upper boulders in the sun." Nature is the force tearing down this wall, and we like to think that nature is a force for the righteous and the good.

brings the two neighbors together. Frost is tricky because we tend to read his invocations of nature romantically. "Something there is that doesn't love a wall/ That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it,/ And spills the upper boulders in the sun." Nature is the force tearing down this wall, and we like to think that nature is a force for the righteous and the good.