Sort of:

(Hat tip: 3QD)

Rick Hertzberg remembers his own Diana Trilling moment (it was with his mom).

A reader writes:

I’m interested in your posts on divinity. I very much enjoyed the article in the New Yorker that you linked to last week. I think it gets to the nub of the issue — that the Orthodox conception of Jesus holds up as long as you don’t think too much or learn too much about it.

I was fairly Orthodox (albeit liberal) christian for most of my nearly five decades, but after reading a host of scholarly literature, including Bart Ehrman and James Tabor, it’s hard to maintain that faith. The fact is that once you delve into the details, you will discover that the widely taught idea that “we believe what has been handed down from the first Christians” is plainly false. One has to seriously twist the meaning of the gospel writers in order to assert that they were teaching Jesus’ divinity. Clearly phrases such as “Son of God,” which we are taught refers to divinity, did not have the same meaning to the authors. Clearly, doctrines such as Jesus’ divinity and the resurrection immediately upon death were developed over long periods of time.

How does that change one’s beliefs? Well, in order to study history and maintain one’s beliefs, you either have to: 1) deny the facts; 2) develop some system of progressive revelation that encompasses God’s guiding hand over history; or 3) revert into some type of mysticism. None of those options are appealing to me.

The last two options are extremely appealing to me, or rather part of what I regard as the hard work that Christians in our time and place need to do if we are to save a faith in crisis.

Christianity is in crisis – and in a deeper crisis, in my view, than many Christians are allowing themselves to believe. I start from a simple premise. There can be no conflict between faith and truth. If what we believe in is not true, it is worth nothing. The idea that one should insincerely support religious faith because it is good for others or for society is, for me, a profound blasphemy if you do not share the faith yourself. I respect atheists and agnostics who reject faith; I find it harder to respect fundamentalists – of total papal or Biblical authority – because of the blindness of their sincerity; but I have no respect for those who cynically praise religion for its social uses, while believing in none of it themselves. Sadly, a critical faction of the Straussian right has been engaged in exactly that kind of cynicism for a while now.

But if religion and truth cannot be in conflict, Christians who believe in a God of logos have an obligation to make sense of those moments when modern learning disproves certain religious preconceptions. No modern Christian, it seems to me, can claim the literal inerrancy of the Bible without abandoning logos. No educated Christian today can deny that the scriptures we have – copies of translations of copies of copies of oral histories – are internally and collectively inconsistent, written by many authors, constructed in specific historical contexts, reflecting human biases, and supplemented by several other gospels that at the time claimed just as much authority as those gospels eventually selected by flawed men centuries later. Anyone who believes that the Holy Spirit automatically guides every church leader to the perfect truth at all times need only look at the current hierarchy to be disabused of such childish wish-fulfillment; or cast an eye on church history for more than a few minutes.

So the solid architecture of the faith we inherited has been exposed more thoroughly in the last few decades than ever before. There is no single authoritative text, written by one God, word for word true. There is a much more complicated series of writings designed by many men, doubtless under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, that help us see some form of the figure Jesus through languages and texts and memories. I think the character and message of Jesus are searingly clear and distinctive even taking into account that daunting veil through which we are asked to see. But we can only begin to see this once we have understood the veil that both obstructs and made possible our view.

The same, I think, is true of the papacy as an alternative to Biblical literalism. This is in some ways a more durable defense against logos than Biblical literalism, but it is just another form of fundamentalism, deploying total obedience to total authority as an alternative to a living faith that can both doubt and yet also practice the love of God and one’s enemies, Jesus’s core instructions. I do not see how the limits and flaws of such total authoritarianism could have been more thoroughly illuminated than in the recent sex abuse scandal. When the man whose authority rests on being the vicar of Christ on earth consigns children to rape rather than tarnish the image of the church, he simply has no moral authority left. Yes, his position deserves respect. But its claims to absolute authority have fallen prey to the human arc of what Lord Acton called “absolute corruption”.

So we are left in search of this Jesus with a fast-burning candle in a constantly receding cave where we know that at some point, the darkness will envelop us entirely. We will catch Him at times; He will elude us at others. We will have to listen to many words he may have spoken before we can each discern the words he may have meant; we will have to keep our eyes and ears open for science’s revelations about the world, while understanding that science is just one way of understanding the world and that poetry, history, and practical perspectives have things to tell us as well. The cathedral at Chartres; the long story of Christian debate and theology; the rituals and daily practices that help us stay trained to intuit the divine we cannot understand and the divine we do not always see in every face around us: these too tell us things that go beyond fact, archeology and hermeneutics.

Yes, this intellectual sifting is hard and troubling to faith; yes, it may end with more mystery than clarity. But if our faith is to be true, it must rest on something more than denial of reality. It must rest on being the greatest experience of reality.

“Be not afraid! Of what should we not be afraid? We should not be afraid of the truth about ourselves.”

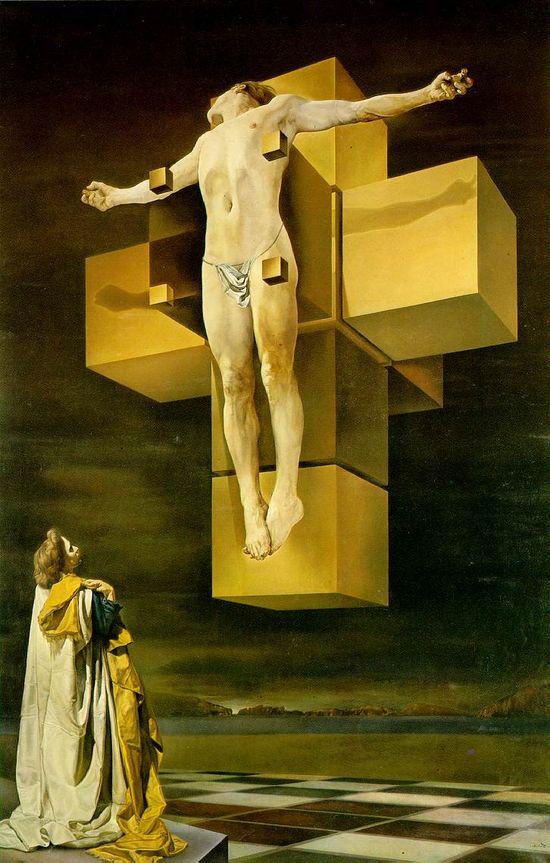

(Painting: Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus), 1954, by Salvador Dalí.)

An extract from a 1967 documentary about hippies. What’s interesting to me is the anti-political nature of this “cultural revolution”. This was about shifting personal human values as a way to change society: change without power:

It cannot be easy having a 1981 thesis being read by professional historians decades later. But there appears to be universal consent that her work holds up remarkably well:

On the whole, Kagan writes without evident bias, analyzing quite evenhandedly the rifts—which at times she suggests were doomed to be insurmountable—between the revolutionary and reformist camps in the Socialist Party as well as in the International Ladies Garment Workers' Union. If anything, Kagan seems to have more sympathy for the centrist "constructivist" leadership than do many historians who write about labor and radicalism. Her overall point, made without stridency, is that sectarianism, caused mainly by misguided revolutionary hopes, should ultimately bear the burden for the party's demise. Socialists, she seemed to say with some sadness and frustration, have often been their own worst enemies. In places, her tone even implies that she may consider this an ongoing characteristic of the American left. "Radicals have often succumbed to the devastating bane of sectarianism," she wrote; "it is easier, after all, to fight one's fellows than it is to battle an entrenched and powerful foe." In any case, there is no question that Kagan wrote not a propagandistic celebration of socialism's heyday but a judicious account of its self-destruction—with the hope that the left might learn from past mistakes.

There can be few doubts about her intellectual abilities.

A reader writes:

I wanted to tack this onto the post "At The Hour of Their Death."

12 years ago my mothers passed away after a 9-month battle with cancer. I was in the room as her body gave up her spirit. It was that clear. Her forced breathing. The tension in her neck and face. The physical energy left inside the very sick and very emaciated body must have been so little, but the change in her appearance at that final moment was vast. Her body gave up her spirit. The air in the room took on a very distinct quality. It seemed a moment when anything could happen. That the air could shimmer and tear apart and I would not have been surprised.

The air was similar at the birth of my three children. When my children were born anything could happen. The air was filled with a remarkable energy. A moment when all laws of nature, all science, all proof, everything man knows about existence and life was so limited. Religion is not all about "fear of death" – it is also because we have all witnessed things that science and learning cannot explain.

Another reader:

Atheists, from my own experience (and I did not always identify myself this way; I still prefer god-free to atheist, as it implies being against something), don’t think about death much at all, except when we ponder its inevitability, our own experiences of loss, and the way it has of telescoping time.

When my partner died in 1991 I’d been mostly an atheist, though I didn’t spend much time defining that for myself. But when he died, I had an experience similar to the nurse’s. I was suddenly convinced that he had been a person, a spirit, and now he was gone. I searched and wondered, and I started going to a church I’m still fond of and will still attend from time to time. I was most perplexed by where he went. Many years later, I’m at peace with the whole issue. I need neither to believe not to disbelieve.

Your reader's sense that the people who died in her presence were gone is quite accurate and there’s nothing supernatural to it. But the underlying sense she has, and that I had, that the person had gone somewhere, is at the heart of the matter. We are indeed gone when we die, but we do not go anywhere. It is the living we leave behind who grapple with the question of where we have gone, and interpret the experience to mean there is somewhere to go and our spirits have left our bodies en route. What leaves our bodies is life, and life is energy. So, yes, we are here and then we are not, and it’s all quite mystical and profound, but it does not require an afterlife of anything but silence. Why that is not enough for so many, many, many people is something I understand but don’t participate in. An anecdote has it that when the Buddha was asked if god exists, he remained silent. I have always loved that. He did not say yes and he did not say no. I interpret that to mean that he had no need to answer the question.

A final reader:

Your reader's reference to a "palpable feeling of departure" when someone dies reminded me of a couple of scenes from the movie (and person) "Temple Grandin". Ms. Grandin is a highly functioning autistic person whose autism seems to have bestowed upon her an unusual ability to observe and recall small details. In the movie, there is a scene in which she witnesses a cow's instantaneous death in a slaughterhouse. "Where does it go?", she asks the slaughterhouse manager, who thinks she is asking what the next step is in processing the cow into beef. But really what she wants to know is, one second there was a cow there, the next second there was only beef – so where did the living, aware cow GO?

Later in the movie she asks the same question at the funeral of a teacher who meant a great deal to her. She is not saddened to see the body, but she still wants to know, where did he GO? Temple does not experience the emotional loss of death the way most of us do, but she is acutely able to sense that something has left the body.

(Photo: Terminally ill patient Jackie Beattie, 83, touches a dove on October 7, 2009 while at the Hospice of Saint John in Lakewood, Colorado. The dove releases are part of an animal therapy program designed to increase happiness, decrease loneliness and calm terminally ill patients during the last stage of life. The non-profit hospice, which serves on average 200 people at a time, is the second oldest hospice in the United States. The hospice accepts patients regardless of their ability to pay, although most are covered by Medicare or Medicaid. By John Moore/Getty Images.)

Grand Gorge, New York, 6.50 pm

Salon speaks with Amie Klempnauer Miller, author of the parenting memoir, "She Looks Just Like You":

Non-biological lesbian moms, like gay fathers who use surrogates, we're in this weird zone between motherhood and fatherhood. I had tried to get pregnant, but, in the end, it was my partner who carried the baby, and I found myself going, "Wow, so what's my role here?" I was planning on taking maternity leave, but I wasn't pregnant. I was there for the conception, and I was there for the ultrasound but I wasn't going to get to do these things, like childbirth, that are so paradigmatic of what it means to be a mother.

The parents I ended up relating to the most were stay-at-home dads because they are bending the genre categories themselves. It's interesting that some of the criticisms that have been made toward stay-at-home dads are not that different from the criticisms of gay and lesbian families. Is it natural? Will the kids turn out OK?

A pwntastic spoof of Owl City and other synthpop groups:

"[Kagan's] thesis — written from the perspective of an anti-communist scholar who was not in sync with the pro-communist leftism of what by then was a declining New Left — does not reveal that she was an advocate of radical social change. It does reveal an individual who, like the socialists and unionists she was writing about, also wanted to “change America.” It is clear that she found their struggles inspirational and that she empathized with their fight. If she has not changed her views on these issues, it puts her right in the mainstream of what is today’s left-of -center Democratic Party … Some may disagree with the political sympathies that led her to write on this topic, but I believe the thesis itself should serve as no grounds to deny her appointment to the Supreme Court,"- Ron Radosh, Pajamas Media.