Berlin, Germany, 2.37 pm

Berlin, Germany, 2.37 pm

Bailey tries to quell concerns over man-made organisms:

No one is talking about releasing synthetic organisms into the environment at this stage. The Venter team “watermarked” the synthetic cells with unique genetic sequences to distinguish them from natural cells so that they could keep track of them. And before getting too worked up over the potential dangers of escaped synthetic microbes, keep in mind that humans have been moving thousands of exotic microbial species across continents and oceans for centuries. Surely, some have had deleterious effects, but the world has not come to an end.

In any case, many lab-crafted creatures would likely be obliterated by competing organisms honed by billions of years of evolution in the wild. In the future, synthetic organisms could be equipped with suicide genes where their survival is dependent on some chemical that is only available in the lab. For example, if synthetic microbes are created to treat some kind of pollution, they would be supplied with the chemical onsite and once their work was done, they would be starved of it. In addition, future synthetic lifeforms should be “watermarked” like Venter’s new microbe so that their creators can be held accountable for them.

A moment of silence:

(Hat tip: 3QD)

A Protestant reader writes:

To my eye, death is the most proximal intrusion on our lives of a more general fact — the finiteness of our lives in contrast to the infinity (or nearly that) of time and space. The questions that once bothered me did not verge towards, "do I live on after death?" but ran more towards the cosmic. As quickly as I can summarize, "if I am just strutting and fretting my nanosecond upon an infinitesimally tiny stage in the great arc of the universe, with any evidence of my life disappearing in a few scant thousand years, with my species but a midget latecomer on a single planet around a single star, ready to be snuffed out at any moment by a passing asteroid or our own cleverness, just what the hell is the point of my getting out of bed this morning?"

The answer, in as much as I've been able to come up with one, is that I am faced with a question which is utterly beyond scientific inquiry or rational consideration. I can either believe that, as the great American prophet of the 20th century observed, "the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice," and attempt to play my bit part in that play, or I can believe that this is false and that it is all a stack of amoral laws and properties and waveforms and such, and that any actions I take are, in the not-very-long run, utterly and completely moot. I make the conscious decision to believe the former, which is to my theology (and, despite what atheists looking for a straw man might rush to argue, that of my church), a statement of religious,

irrational belief in God.

This problem does not, however, restrict itself to cosmic meditations. Your passage on your dying friend reminds me that in the experience of my life and those close to me, religion is not nearly so important in contemplating one's own death but in contemplating the deaths of those to which we are closest. The spiritual challenge of one's own mortality is tiny and remote compared to the challenge of the mortality of one's children or other dearest loved ones. I can contemplate my own finitude with little disconsolation, but as I think of childhood friends who died far too soon, something not from my rational faculties begins to cast frantically about, trying to seize upon something which might suggest some part of them lives on — that memories and objects somehow preserve the person I felt close to. Surmises that "what a person does lives on in the lives of those touched by him or her" strike me as only slightly less irrational than the supposition of an immortal soul.

On a similar note to loss, there's the human problem of absence. In an exchange some time ago on your blog, one atheist reader angrily replied to religion's role in providing comforting words that as atheists, his family relied on each other. I'll certainly not interfere with this form of support, but the question remains — what of those who lack some or all of their family? What of missing or abusive parents? While I look through the eyes of a believer, I can't see a "vast chasm" between on the one hand a perfectly rational orphan who, in times of despair, relies upon the belief that there are forces for good in the world which can lift her up, and on the other hand Obama's "audacity of hope," which didn't seem to trouble too many atheists.

In my own times of trouble, I've consoled myself with my belief that there is good inherent in the world, reinforced this with songs, scripture, and poetry, and called that force the Holy Spirit, but that doesn't seem any more of a stretch than ascribing the rain to Mother Nature or taxes to Uncle Sam. (I feel considerable sympathy with a Jesus of Nazareth who, divine or not, clearly realized at an early age that Joseph was not his father, and who called the God of Israel, Abe, or "daddy.")

At extreme risk of sounding just as condescending and trite as the "you can't deal with death" atheists, I have to observe that it's much easier to say goodbye to a happy, healthy life than to one filled with unfairness and injustice and illness. If we're going to be ascribing religious beliefs to mental failings, I'm far more ready to accept that it comes from the offense to our innate sense of justice when a selfless and caring person suffers a long, horrible, painful, and lonely death than some fear of the terminal dark. It's far easier to accept an "unjust" death if one can imagine the soul sleeping peacefully in the arms of the Savior than imagining that years of humiliating pain are the final word on a life. Indeed, I confess to thinking that atheists are even able to hold these more scornful takes on religious belief because they haven't come face to face with truly horrible pain and suffering in their lives. Whatever gets you through that, I'm pretty sure it doesn't come from rational consideration.

And, if I may add something to this deeply personal note, reducing this religious experience to a "crutch" presupposes that a crutch is somehow unnatural. But this experience of suffering and loss and death is part of the core human experience. Which is why faith endures. Modernity has helped keep this suffering at bay – numbing it with pharmaceuticals and technology and material comfort previously unknown.

But it hasn't changed our deepest reality; it has merely muffled it and enabled our denial some more. Death comes. Injustice remains. Unfairness triumphs. On this earth, at least.

But what sort of Jew? A Catholic scholar of the historical Jesus, John P. Meier, explains:

A reader dissents:

The Internet is not doing anything to our brains. We may be doing bad things to our brains. But the things that we are doing have been possible as long as there have been libraries.

Any library patron has always been free to read a paragraph, re-shelve the book, grab a new one, skim its preface, re-shelve it, wander to the periodicals section, grab the New York Times magazine, flip to the fancy real estate ads in the back, think of West Egg and East Egg and Jay Gatsby, put down the magazine, head to the fiction section, reach out for Fitzgerald's classic, realize that he's never read anything by Fitzgerald's wife, wonder if this makes him a sexist, decide that it just might, scan the fiction Fitzgeralds until he finds Zelda, grab a copy of Zelda's "Save Me the Waltz," start to read the first paragraph, question his own memory, flip to the author bio to confirm that Zelda was truly married to the Gatsby author, see that Zelda was born in Montgomery, think of the Montgomery bus boycott, remember that he's been meaning to buckle down and read Taylor Branch's MLK biographies, head off for the biography section.

Etc.Etc.Etc.Most of us don't do that in libraries. But we could.If Carr's piece causes people to rethink the choices they make online, I'm all for that. But I'll be upset if Carr's piece causes people to flee the Internet or to resign themselves to an online reading experience that, to use those words of yours, is "more like watching the landscape from a train." It's not just that we can drive our own train. It's that we're free to jump the track, to go where we want at the speed we want with as many or as few distractions, digressions, and deep-thinking dives as we choose.

By all accounts, David Laws is a decent, brilliant, capable and humane public servant, and had been given a critical role in the new coalition government in Britain: cutting spending. Laws is of my generation, but has been caught, as others have been, by the riptides of social change and the pace of his own personal journey. He came out only recently and struggled with being gay and wanting to be in elective politics for a long while. One of many reasons he is a Liberal Democrat and not a Tory is his sexual orientation. And so the new government in Britain was Laws' moment. And yet it was also his undoing.

He has just been forced to resign over an expenses scandal. There is an allowance for members of parliament to get accommodation in London while they live in their constituencies. This allowance went to his partner, for their shared apartment in London. Because of the closet, Laws concealed this relationship and fell foul of the rules. He didn't personally benefit from the money – his partner did – but the rules were indeed broken. And so an extremely promising career has been temporarily derailed.

With any luck, Laws will return to government at some point. Britain needs him. For me, this is just an example of how the closet distorts the ethics of good people, and leaves them open to abuse, blackmail, or simple, forgivable conflicts of interest – because lies about the deepest aspects of ourselves rarely stop there. They require other lies and fibs and white lies … which in time, degrade someone's integrity, and often leads into traps, like the one into which David Laws just fell.

A spouse, for example, who is not publicly a spouse means that the usual full disclosure of conflicts of interest is impossible. And so Law's nine-year relationship – effectively a marriage – made sense in one setting and broke the rules in another.

The way forward, it seems to me, is to ensure that when we are dealing with high level public figures – Treasury ministers, Supreme Court Justices, Cabinet members, et al – the gay question be no longer shrouded in discretion and ambiguity and taboo. As our society evolves, the closet will always remain an option for those too afraid or too conflicted or too uncomfortable to be open. But in public life, especially at its highest reaches, it has to end. And the press must stop enabling it, and start tackling it. Not out of personal vindictiveness and not out of cruelty. But because emotional and sexual orientation is a fact about people. In my view, public figures in national capacities need to be open about this or not seek high office. And if they do seek high office, they need to expect to be asked and to tell. Honestly.

Because lies, even white lies, even understandable lies, cannot last in today's culture and today's media.

Update: Iain Dale has an excellent set of reflections on this here.

A thoughtful but still Orthodox Christian explains. What's staggering to me is that a couple of verses in the Bible carry more weight for this person than all the evidence in front of him. Rather than adjust his understanding of Biblical literalism and authority, he adjusts his view so that the Fall must apply to monkeys too. They just don't know it.

A small glimpse into modern Christianity's crisis.

A reader writes:

Your reader says Paul is is "clear as anything you could want," but then he he cites only example from Paul. The same passage (Philippians 2) was cited by another reader, and I agree that the verses are likely to be some sort of early Christian hymn. However, I don't think it means what people want it to mean.

If one tried to discover a consistent position of the biblical authors (both Old and New Testaments) on the question of divinity, the closest would be the principle of "agency." God's earthly representatives were considered "God," not because they were actually God by nature, but because they were acting on his behalf. It is the point Jesus made when he was questioned about claiming to be God in John 10. We don't think that way today, but it was a rather typical way of looking at things when the bible was written.

Back to Philippians, here is a quote about the passage from scholar William M. Wachtel:

"It suggests that Christ as a Man on earth was functioning in the status, rank, or position of God. Amazing thought! But there had been a famous historical precedent for this. When God called Moses to be his agent to bring Israel out of Egypt, he told him, “See, I have made you like God to Pharaoh, and your brother Aaron will be your prophet” (Exo. 7:1). The Hebrew text is even more startling, because the word “like” is not there at all. Rather, God declares to Moses, “I have given you [to be] Elohim to Pharaoh.” Earlier, God had said that Moses would be “Elohim” to Aaron (4:16). This means that Moses functioned in some ways as though he were God on earth; he was the appointed leader to act for God and as possessing the authority God had conferred on him by designating him to bear Yahweh’s own title, Elohim!"

Those who claim that worshipping Jesus as a member of the Godhead went back to the first Christians also have to account for Jesus' brother James, who was the head of the earliest Jesus movement according to a host of non-Canonical and biblical sources. James was a respected Jewish figure and leading figure in the Jerusalem temple for several decades at the same time he was leader of the early church. His murder caused the Jews to send a delegation to Rome in protest.

If James had been a Trinitarian, there isn't the slightest chance that he would have been able to co-exist peacefully within the temple.

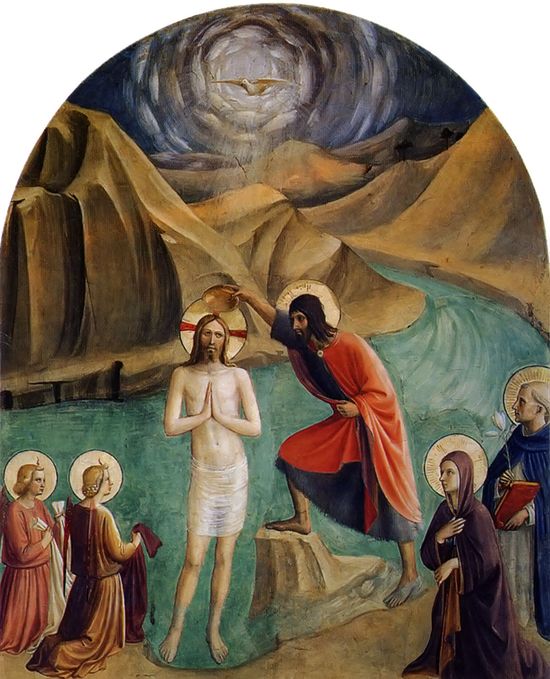

(Painting: The Baptism of Jesus by Fra Angelico.)

Nick Carr continues to lament how the internet has changed reading:

The depth of our intelligence hinges on our ability to transfer information from working memory, the scratch pad of consciousness, to long-term memory, the mind’s filing system. When facts and experiences enter our long-term memory, we are able to weave them into the complex ideas that give richness to our thought. But the passage from working memory to long-term memory also forms a bottleneck in our brain. Whereas long-term memory has an almost unlimited capacity, working memory can hold only a relatively small amount of information at a time. And that short-term storage is fragile: A break in our attention can sweep its contents from our mind.

Imagine filling a bathtub with a thimble; that’s the challenge involved in moving information from working memory into long-term memory. When we read a book, the information faucet provides a steady drip, which we can control by varying the pace of our reading. Through our single-minded concentration on the text, we can transfer much of the information, thimbleful by thimbleful, into long-term memory and forge the rich associations essential to the creation of knowledge and wisdom.

On the Net, we face many information faucets, all going full blast. Our little thimble overflows as we rush from tap to tap. We transfer only a small jumble of drops from different faucets, not a continuous, coherent stream.

I know Carr is a broken record on this, but I don't doubt he's onto something. Since blogging – and the demands of blogging – has taken over much of my writing and reading life, I find long-form books, which were once a staple of my education, harder to read. And although I seem able to process and retain large amounts of information and facts on this blog on a daily, hourly, basis, soon they have to make way for more. My ability to forget has grown as my consumption of data has increased.

I don't think this is really best described as reading. Reading takes time, especially if you read slowly, as I do. A real book takes longer to absorb. You need to let a great book wander around your mind as you go along. Online, there is no wandering. The journey is so packed, the distances so great, it is more like watching the landscape from a train.

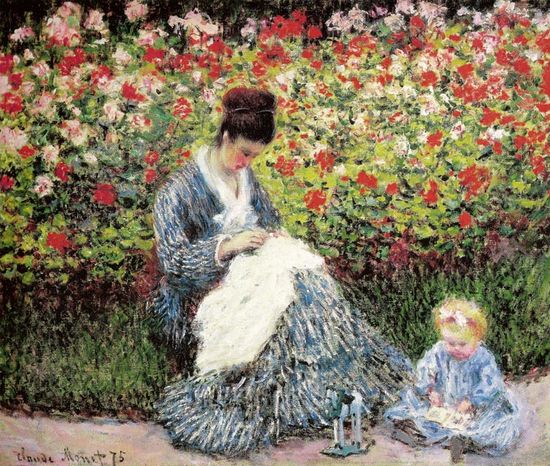

(Painting: “Camille Monet and a Child in a Garden”, 1875, oil on canvas, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)