by Chris Bodenner

B. Daniel Blatt has an opinion about which is easier.

by Chris Bodenner

B. Daniel Blatt has an opinion about which is easier.

by Patrick Appel

Jeb Koogler spotlights the floods of Pakistan:

Attention to the crisis has been heavily focused on the security angle. The dominant narrative regarding Western aid is that Pakistani extremist groups are gaining influence by controlling the aid distribution process, and that the West should thus increase its own aid distribution in order to counter these radicals. John Kerry, for example, visiting the region last week, mimicked this line of thinking: "Miles upon miles of destroyed homes, of people dislocated, people in camps in great heat, losing their possessions, growing frustrated, worried about the future. We need to address that, all of us rapidly, to avoid their impatience boiling over or people exploiting that impatience."

But note how this narrative obscures the humanitarian angle, and downplays the notion that governments have a responsibility to assist peoples beyond their borders. Our aid policy in the wake of this crisis should largely be constructed and justified based on a notion of shared humanity — not merely on a narrow assessment of American interests. That Pakistanis are suffering and desiring of international aid should be enough to warrant our attention, our dollars, and our support.

Via Joyner, who rounds up more analysis.

by Conor Friedersdorf

In Montgomery, Alabama, government officials are destroying the property of poor people:

Imagine you come home from work one day to a notice on your front door that you have 45 days to demolish your house, or the city will do it for you. Oh, and you’re paying for it.

This is happening right now in Montgomery, Ala., and here is how it works: The city decides it doesn’t like your property for one reason or another, so it declares it a “public nuisance.” It mails you a notice that you have 45 days to demolish your property, at your expense, or the city will do it for you (and, of course, bill you).

Your tab with the city will constitute a lien on your property, and if you don’t pay it within 30 days (or pay your installments on time; if you owe over $10,000, you can work out a deal to pay back the city for destroying your home over a period of time, with interest), the city can sell your now-vacant land to the highest bidder.

by Zoe Pollock

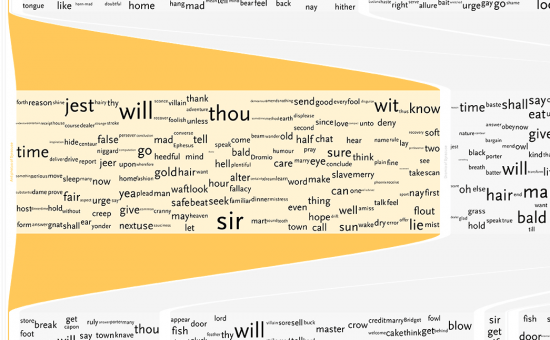

Stephan Thiel at the University of Applied Sciences Potsdam has charted Shakespeare in various ways as part of his B.A. thesis:

The goal of this approach was to provide an overview of [each] play by showing its text through a collection of the most frequently used words for each character.

My favorite is how often "Oh" seems to occur in Romeo and Juliet. Oh, young love…

(Hat Tip: Flowing Data)

by Conor Friedersdorf

In California, local government is where our political failures begin.

Does anyone pay regular attention to their City Council or County Board of Supervisors? The people in Bell didn't, and were typical in that way. Those local bodies are used as stepping stones to the state legislature and beyond. But the folks who rise aren't doing so based on the considered judgment of citizens so much as their ability to curry favor with donors, spend on campaign advertising, and win elections via name recognition.

It's a contest that's grown too sophisticated for amateurs.

Several factors militate against civic engagement. Ours is a large state with huge counties that contain sprawling municipalities. Our population is famously transient. A series of progressive reforms and populist ballot measures (especially Proposition 13) tended to strip control from local authorities, so that Sacramento grew in political importance. When the County Board of Supervisors sets property taxes, residents damn well show up at the meetings, whereas scrutiny is orders of magnitude less when the most contested subjects are settled regionally.

Nowadays so many critical matters of public policy are being decided by anonymous, faraway state officials, or even worse, their federal equivalents. In a way, life is less burdensome for people when they can safely ignore local civics, but the price in dysfunction and ceded influence is high. The thing about national or even state elections is that voters can only get their information from the mass media or professionally run campaigns. Though these are the best methods we've got, they are pretty terrible. Have you watched cable news lately?

Those of us who advocate federalism, and want states to give as much control as possible to locals, aren't just cranks who worry that tyranny is going to sweep the land if a marginally looser construction of constitutional law prevails. Our insight is that self-government works best when important matters inspire civic participation at a level where it can actually matter.

On Wednesday nights, a ten minute car ride is sufficient to arrive at city hall in time for the weekly meeting, where you can stand up at a podium, speak your mind directly to actual decision-makers, and respond if you still don't get your way by talking with people afterward — the ones who cheered when you spoke up, and might even be willing to back your own run at local elective office. These kinds of encounters inspire confidence that regular people can make a difference.

And we'd be far better off if our politicians started out as folks with particular passion for grassroots civic efforts, rather than coming from a power hungry class drawn by the prospect of a remunerative career in elective office.

Everything about national politics is awful. The candidates, the disingenuous talking heads, the artificially binary separation into Team Red and Team Blue, and especially the lack of weirdness, which is another way of saying that American communities and people are a quirky sort. Their diverse approaches to the pursuit of happiness are given short shrift if they're always forced to make consequential decisions in concurrence with everyone else.

by Conor Friedersdorf

In Cato Unbound, Glenn Greenwald's essay on the surveillance state is now posted alongside comments by John Eastman, Julian Sanchez and Paul Rosenzweig. Mr. Greenwald has a response up here. It's a good debate, and another illustration of how the liberty versus tyranny framework isn't very useful for assessing liberal arguments.

by Chris Bodenner

Geekologie says it best:

Not cool, Field Center for Children's Policy, Practice & Research, not cool.

by Conor Friedersdorf

Phillip writes:

Since you have a platform to ask interesting questions (and get back interesting answers), I have one I'd like to have asked, dealing with the way Americans of differing ideologies frame their debates.

My own camp is generally "not conservative", so I often feel I'm among the targets of conservative denouncements of liberal "tyranny." And some of what they say makes sense. While I'll admit to being in the liberal camp, I'm pretty centrist (e.g. I actually feel like Obama is delivering what I heard him promise during his campaign), so conservative calls for smaller government and greater personal freedom do resonate with me.

Still, I'm never actually convinced it's anything beyond rhetoric, mostly because of a single, gigantic exception – conservatives give the military (and really anything security-related) a huge bye. I can understand the argument, for instance, that if taxes are too high then personal freedom is to some degree eroded, but that seems very metaphorical compared to government's power to physically lock you up. For all their talk about freedom and liberty, the enthusiastic embrace of the military and security culture by many conservatives pretty makes that seem like a lot of empty rhetoric to me.

I don't mean it as a critique so much as a question – why does the military-security culture get such a huge pass? I honestly don't understand how you can cast yourself as a defender of liberty on one hand, while be fully in support of expanding the government's ability to physically remove your liberty on the other. (To be clear, I don't expect conservatives to be pacifist – I'm thinking of specific examples like denouncing any criticism of the Iraq war as unpatriotic and casting skeptics of the Patriot Act as loony leftists – and of course, all the torture, er, enhanced interrogations).

by Chris Bodenner

Dan Savage draws distinctions between Andrew Marin and the evangelical pastor who wrote to the Dish. Dan's larger point:

I have no beef with evangelical Christians who support full civil equality for gays and lesbians despite believing that gay sex is a sin. Heck, I'll personally mow the lawns of evangelical Christians who are willing to refrain from actively persecuting gays and lesbians. I've said that it's a mistake to get into arguments about theology with people, and that people have a right to their own beliefs. I don't care if someone thinks I'm going to hell when I die and I'm not going to argue with him for the same reason I'm not going to argue with someone who believes that I'm going to the lost continent of Atlantis when I go on vacation.

All gays and lesbians want from evangelical Christians is the same deal the Jews and the yoga instructors and the atheists and the divorced and the adulterers and the rich all get: full civil equality despite the going-to-hell business. (And isn't hell punishment enough? Do we have to be persecuted here on earth too? It's almost as if they don't trust God to persecute us after we die. Have a little faith, people!)

Scores of readers wrote in with similar sentiments, and I wish I could post them all, but Dan really does say it best.

by Chris Bodenner

A reader writes:

A lesser-known band, but one that's easily as inventive and respected in certain circles as Starflyer 59 and David Bazan, is mewithoutYou. They formed out of the Philadelphia hardcore scene in the late '90s, have been on Tooth and Nail – the same label Starflyer and Pedro the Lion got their start on – since their first album in 2002, and have toured with David Bazan a couple times. The first album was pretty hard stuff, with singer Aaron Weiss doing more speaking/shouting than singing, but each successive album has gotten a little softer, with Weiss singing more and more.

Their fourth and most recent album, "It's All Crazy! It's All False! It's All a Dream! It's Alright!" finds Weiss given over to singing every song and the band playing stuff that is a kind of gypsy/folk sound. It's also the first album ever on a Christian label and sold in Christian stores that's a largely Muslim work. Weiss and his brother were raised by parents who were into the Sufi faith, and this album has that kind of thing all over it. In fact, the album title is a quote from Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, an important Sufi mystic, and some of the songs are his parables [see video above].

For my money, it might be the best Christian album ever. It's got talking animals and food, songs about King David and a baby Jesus, themes of environmental responsibility (the band drives around in an old bus converted to cooking oil), and one-ness with everyone else. It even closes with a song repeatedly using the name "Allah" for God. Musically it's outstanding too, and their live performances are as energetic and engaging as any band I've ever seen.

Weiss talked about his faith with Relevant magazine:

I read that a few years ago, Christianity was just "business" to you and that you wanted to "just make out with chicks" (at one point). It wasn't until you spent a time in a communal living situation that things changed for you. What made you join that commune?

I suppose it was a longing for something real, something different than what I'd known. The Christianity I'd been exposed to was primarily concerned with the afterlife, little concern for people's tangible, immediate needs. We pray, of course, "your kingdom come … on earth as it is in heaven," and I found myself wondering what the world would look like if the kingdom did come, if it were a paradise, right here, today. And it seemed like communal living was a step in that direction.

Have you received direct criticism to your way of life from other Christians? What was it, and how did you deal with it?

Not as much as I'd hope. When criticism does come, I usually think, "Finally, I must be doing something right!"What were your friends' and family's reactions to your life change? Was it immediate, or did the Aaron Weiss we see today emerge slowly?

For a while there was a gradual turning, with one single experience bringing about a sudden and dramatic change almost three years ago. I think people worried about me. I was feverish, couldn't sleep much, woke up trembling. I would ramble on, trying to communicate what was inside, to share what had been given to me. It didn't work—I've had to learn to be quiet, to listen, to show it instead.How does your view of Christianity affect your desire to, or lack of desire, to be married?

Jesus said that it's better for a man not to marry. Paul wrote the same thing. I see it as a sort of a concession I'll have to make if I don't have the faith to find contentment in my God alone. That I may need such a compromise seems likely, as I've always had a passion for that sort of union, and I get lonely. I don't so much mean sexually, but mostly I long for companionship and a deep friendship. If God is willing though, maybe I could find that in the Holy Ghost.

Another reader corrects me on previous entry:

There a small error in your post regarding Neutral Milk Hotel. Mangum did NOT talk about his faith to Pitchfork in 2008. Rather, in 2008, Pitchfork posted an interview from all the way back in December 1997. Big deal, you might say. I bring this up only because Mangum retreated from public life shortly after In The Aeroplane Over the Sea was released and, at least as far as I know, hasn't done an interview in many years so the suggestion he gave an interview in 2008 might surprise a few people.

Mangum's retreat from public life is itself a pretty interesting story. Since about 2001, he has only played at a couple of benefit shows for friends.