From the streets of New York City:

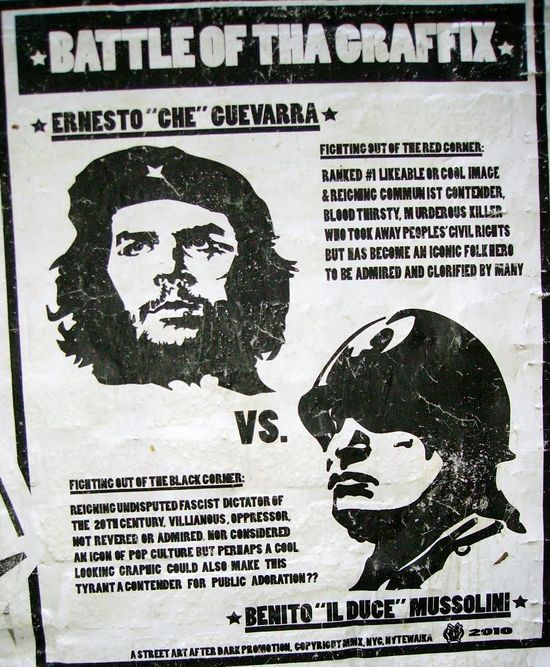

Helpful comparison with Mussolini after the jump:

"I hate to say this, but I set the Internet up. I set the Internet up so they would talk bad about me because it's the only way to get hits," – Basil Marceaux, former gubernatorial candidate but forever in our hearts.

A reader writes:

I enjoy the Dish immensely and rarely find myself in a position of vehement dissent, or find a post just hurtful and shallow. But the one on Dan Ariely's research hit a nerve. He did near-anecdotal research finding that we feel like big jerks if we discover we've laughed at a person with a legitimate disability. We even try to see the good in them when we realize they're overcoming an obstacle. Then he extrapolates to say that this encourages us to embrace labels so that we can offload blame.

As a parent of a son who has had extreme difficulties with schoolwork and getting along with peers since he was in preschool, I have felt the hurt and the stigma when the other parents judged him as a "weird kid" and me as a "bad parent". My son has shouldered the "blame" for his behavior since he was three, and I have shouldered the "blame" for my bad, bad parenting – parenting that somehow doesn't seem to have the same effect on my other two kids. I have listened to endless streams of criticism and inane advice from people who are pretty sure they know how to solve his problems, if only I were a good enough parent to listen.

Finally, after reading every book, trying a new (expensive) school, therapy, and medication, we have an Autism Spectrum diagnosis.

The behavior is no more socially acceptable than it was before, and we still have the long, hard road of helping this child become a happy, functioning adult. The difference is now we can get the right help, read the right books, address the right issues, and, quite frankly, ignore a lot of stupid blame and advice from people who aren't fighting the same battles.

The label doesn't make the road any easier, but it does help us pick the right path. And I just don't have time for the people who need to place blame on a child or a parent, or imagine that a diagnosis is an easy out.

Another writes:

Ariely appears to conclude that disorders like ADHD are manufactured so parents can blame the disorder rather than themselves or their child. I assume he would lump Asperger's (an autism spectrum disorder) in with his "medical label" theory. As someone with ADHD and Asperger's whose children have ADHD, Asperger's, and sensory processing issues, it frustrates me when people with no experience or expertise (like Ariely, Bill Maher, Arianna Huffington, Dennis O'Leary, and Michael Savage) intimate that these conditions are somehow fabricated or exaggerated, and if parents only did X or Y, their kids would behave better.

While it is fair to debate whether these "labels" are disorders or merely differences, it is conclusive that individuals with these diagnoses differ physiologically and genetically from so-called "normal" people. Kids with ADHD are not simply "energetic," and kids with Asperger's are not merely "a little odd." Only someone who never parented a child with these conditions could think this.

Like me, children with these conditions used to grow up without the benefit of labels to explain their socially incorrect behavior. And like me, many were physically punished or ostracized, yet the behavior inexplicably persisted. In my experience, parents more often blame the child, rather than their parenting (especially if they also have a "good" child as a comparator).

It is other people who blame the parents. For decades after autistic behaviors were assigned a medical label, mothers were blamed for not bonding with their children correctly, so I do not see how Ariely concludes that the labels serve to relieve parents of guilt. Further, is he implying that parents of these children are guilty of something? Maybe he agrees with Savage, who said autism is the result of parents failing to punish their "brats."

When I learned my kids had Asperger's, a friend said, "I'm sorry." I pointed out that my sons' behaviors and my concerns predated the label. The label did not change who they are; it only changed how I interact with them and how I teach them to interact with the world. Without the label, I don't know if I would have ever figured them out. It was like someone gave me a key to understanding them and myself.

Ariely's attitude about these behavioral conditions reminds me of how people used to view depression: as something people could just "snap out of" if they so desired. Today, most people (save the Scientologists) accept that severe depression is a true medical condition. Fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome have also gained acceptance as real disorders. I look forward to the day when people no longer question the validity of Asperger's, ADHD, OCD, and other behavioral conditions with physiological causes.

"When we think of Islam we think of a faith that brings comfort to a billion people around the world. Billions of people find comfort and solace and peace. And that's made brothers and sisters out of every race — out of every race. America counts millions of Muslims amongst our citizens, and Muslims make an incredibly valuable contribution to our country. Muslims are doctors, lawyers, law professors, members of the military, entrepreneurs, shopkeepers, moms and dads. And they need to be treated with respect. In our anger and emotion, our fellow Americans must treat each other with respect. Women who cover their heads in this country must feel comfortable going outside their homes. Moms who wear cover must be not intimidated in America. That's not the America I know. That's not the America I value," – former president George W. Bush.

From his autobiography, talking of his seminal Virginia Statute For Religious Freedom:

Where the preamble declares that coercion is a departure from the plan of the holy author of our religion, an amendment was proposed, by inserting the word 'Jesus Christ,' so that it should read 'a departure from the plan of Jesus Christ, the holy author of our religion.' The insertion was rejected by a great majority, in proof that they meant to comprehend, within the mantle of its protection, the Jew and the Gentile, the Christian and Mahometan, the Hindoo, and infidel of every denomination."

My italics.

That eye-roll is unmistakable. Education is a sign of elitism, remember.

The youthful misadventures of Rand Paul.

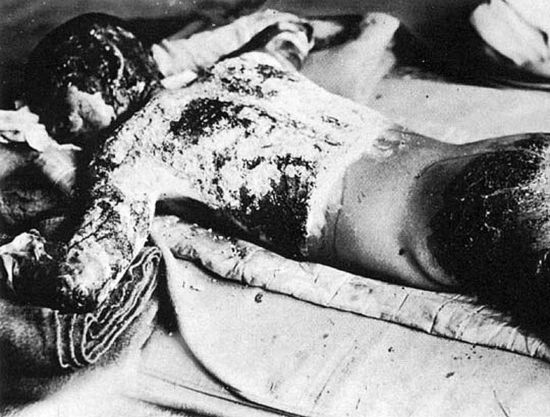

Today marks the 65th anniversary of the United States dropping an atom bomb on Nagasaki, killing 74,000 people and precipitating the end of World War II. James Poulos reacts to a Japanese gentleman who wants an apology:

I confess the purpose escapes me of an official apology for the atom bombing of Japan. "We're sorry we didn't follow through with plans for a massively bloody and protracted invasion of Japan, accompanied, as no doubt it would be, by conventional carpet bombings and city-wide firestorms." Hmm. "We're sorry that you proved so unwilling to surrender Iwo Jima and Okinawa that we thought twice about how to win the war of aggression that you started against us." Could enlist the support of our customer service industry? "We're sorry that you feel that way." Atomic warfare is obviously horrific, and we should all be very pleased that Hiroshima and Nagasaki were the last of it. But apologies mean the guilty party should've done something else, because that something else would have been better for everyone.

Robert Fisk argues toward a very different conclusion. Life has photos. And most astonishing is this surreal story about how a survivor of the Hiroshima blast met the pilot of the Enola Gay during a stunt on national television.

(Photo: one of the burnt victims of Hiroshima.)

Funerals are so formulaic; it's time weddings were as well. Enough of this solipsism and self-love, thunders Andrew Brown, echoing a splendid creed from Giles Fraser (at the 1 hr 48 minute mark here):

The great point about completely impersonal ceremonies, whose form is the same for everyone, whether these are religious or entirely civil, is that they remind us that the problems and difficulties of marriage are universal. They come from being human. They can't be dodged just by being our wonderful selves, even all dusted with unicorn sparkle.

On your wedding day you feel thoroughly special, and your guests will go along with this; so that is the moment when the ceremony should remind you that you're not all that. What you're doing isn't a step into fairyland. And if it does turn out to be the gateway to a new life, that is one that will have to be built over time and unglamorously with the unpromising materials of the old one.

I take the point; although we wrote our own vows. Marriage, I discover, is work; it requires patience and forgiveness and a willingness to go to only conventional war over toothpaste lids, sprinkled toilet seats, dog hair, and travel plans. The lower the expectations the greater the rewards.

But without the torture. This is a description of a prison in Mississippi:

Inmates were locked in permanent solitary confinement. In the summer, the cells were ovens, with no fans or air circulation… The cells were also sewers, thanks to a design flaw in cellblock toilets that often flushed excrement from one cell into the next. Prisoners were allowed outside — to pace or sit alone in metal cages — just two or three times a week. Inside was a perpetual dusk: One always-on light fixture provided inadequate light for reading but enough light to make it hard to sleep. Then there were the bugs… Worst of all, though, was the noise. Psychotic inmates screamed through the night.

And this is the story of how the ACLU and prison administrators successfully joined forces to reform it.