“Once you say that God is a human person — I mean we’re just so varied and diverse that way — I think the real Catholicity of that is to acknowledge that and accept that,” – the Rev. Gilbert Martinez, pastor at St. Paul the Apostle, a gay-friendly parish near Lincoln Center.

Month: April 2011

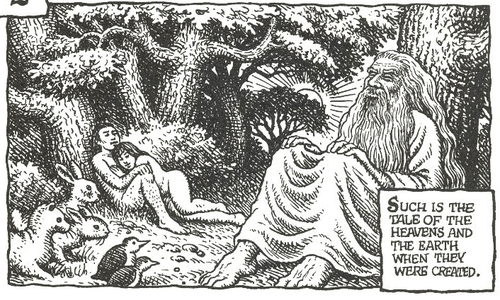

Eve As Hero

Paula Kirby digs into the bible as an anti-feminist text; Maud Newton defends Eve:

Really, who could blame Eve for eating of the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil when she just wanted to be wise? I suppose walking naked with the Lord and Adam, surrounded by plants and animals, was pretty idyllic, but let’s be real. One of her companions was omniscient and omnipotent, and had created the whole world in a week. Why should she have been fulfilled playing the naïf every single day, for her entire life?

(Image from The Book Of Genesis Illustrated By R. Crumb)

Desperately Seeking Certainty

Walter Russell Mead ruminates on Holy Week for Christians:

God seems to believe in keeping it real. He wants us to face challenges that are bigger than anything we know, more complicated than we can figure out, and so dangerous and all encompassing that we are forced to develop our gifts and our characters to the highest possible degree. He wants us to ‘be all that we can be’, and he won’t take anything less.

That’s not how we want it. Human beings want to tame the wild uncertainty that surrounds us on every side. We want that raging sea to calm itself, now. We want predictable returns on our stock investments, and we want steady economic growth. We want to build institutions that can carry on just as they are until the end of time; uncertainty is the dish humans hate most — and it’s the one thing we can count on God to serve.

The Optimal Religion

Babbage sermonizes from the scientific mount:

[Y]ou are better off plumping for a personal god, rather than some sort of indeterminate life force. Research shows that people who profess a belief in such a deity judge moral transgressions more harshly, which in turn tends to make them more willing to abide by the rules, and expend resources on enforcing them.

Childhood In The Church

Kenneth L. Woodward remembers:

During Lent and Advent, we attended Mass each morning before school, marching class by class to our assigned pews. On cold days we heaped our coats and metal lunch boxes on the hissing radiators, and before the mass was over the odor of warming bananas, fruit tarts and bologna, egg salad and peanut butter sandwiches permeated the church. Whenever the parent of a classmate died, we all attended the funeral. The casket was always open and one by one we all passed by, glancing sideways at the cushioned body. At funerals, the priest wore black vestments symbolizing death. On martyrs’ feast days he dressed in red, the color of spilt blood. White and gold expressing joy were reserved for special “feast” days like Easter. Otherwise, the priest appeared in green, the color of that quotidian virtue, hope. In class, we memorized mantra-like the questions and confident answers printed in our small blue Baltimore Catechisms. But it was from images and sounds and colors that we developed our specifically Catholic sensibility.

(Photo by Flickr user Christchurch City Libraries of the church's Flower Girls who "carried baskets of fresh petal flowers every first Sunday night of the month to scatter in front of the Sacramental Monstrance carried by the Bishop in Procession.")

The Messenger

Sally Williams ponders the psychology of death notifications:

What is it like to knock on a door knowing you are about to instigate the worst moment in someone’s life, and then have to confront the ways in which they do or do not deal with the fact that a life has ended? We live in an age where death has been largely exiled offstage. Families used to see it up close, at home; it did not typically involve hospital wards or dual carriageways or a stranger breaking the bad news. And there has been a slow realisation that unless the psychological particulars of that moment are addressed, unless the many challenges of grief and shock are dealt with competently, there can be unwelcome consequences. Which is why a number of fields have begun to wrestle with the problem: how do you break bad news in a good way?

Covering Faith In Disasters’ Wake

Terry Mattingly reads the NYT's coverage of the tornados in the Bible Belt and recalls a long ago conversation with the late Peter Jennings of ABC News:

Anyone who has watched television, said Jennings, has seen camera crews descend after disasters. Inevitably, a reporter confronts a survivor and asks: “How did you get through this terrible experience?” As often as not, a survivor replies: “I don’t know. I just prayed. Without God’s help, I don’t think I could have made it.”

What follows, explained Jennings, is an awkward silence. “Then reporters ask another question that, even if they don’t come right out and say it, goes something like this: ‘Now that’s very nice. But what REALLY got you through this?’'

For most viewers, he said, that tense pause symbolizes the gap between journalists and, statistically speaking, most Americans.

(Photo: Johnny Mizelle of Elm Grove, prays with Samaritan's Purse volunteers in the place his house once stood on April 19, 2011 in Elm Grove, North Carolina. Mizelle lost his home, his farming equipment and 23 hunting beagles during the April 16 tornado that tore through Bertie County. By Sara D. Davis/Getty Images)

A Secular Resurrection

Mark Vernon connects non-religious desires to Christ's rise:

Christianity teaches not resuscitation of the corpse, but the gift of a new body. (Hence, the resurrected Jesus has a body, but it's not like yours or mine – able to appear and disappear, be present but not quite recognised etc.) And is not the desire for a new body one of the dominate narratives in our culture?

Rejuvenating creams, personal trainers, clothes design, body insurance, plastic surgery, virtual reality. I wonder what percentage of the economy is based on a secular, this-worldly version of resurrection? Except that like all desires that are repressed, the original Christian notion returns in a distorted form, purged of the unpleasant talk of death.

The View From Your Window

Bangor, Maine, 12.30 pm

Hate As The Compliment To Love

Ryan O'Connell maps the irony:

With the people you once loved, the people that once had an all-access pass to the most intimate details of your life, you sometimes can’t pay tribute. You can’t ask them about their work, their travels, or god forbid, their family. Your mind can’t process it. They can only exist in black and white; they can either be everything or nothing. You say hello to the person you played with when you were five, and ignore the person whose cum you swallowed, who once cried to you in a cab because everything was going wrong and oh my god, you wanted to help them, wanted to save them.

Who do we hold on to and who do we force ourselves to forget?