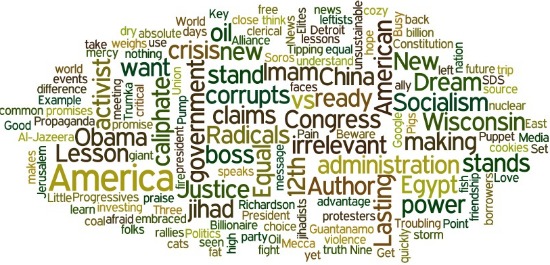

Josh Green notes how far from the dictated RNC-FNC talking points Glenn Beck had wandered. In word clouds! In case you were wondering what Glenn Beck's mind looks like, here you go:

I have to say I prefer its zany zig-zags to Hannity propaganda.

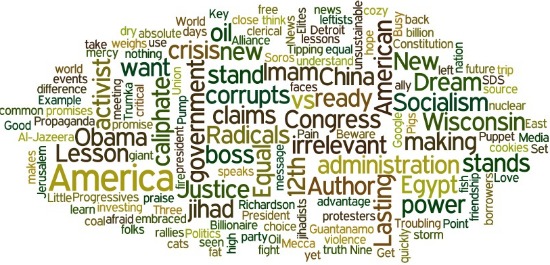

Josh Green notes how far from the dictated RNC-FNC talking points Glenn Beck had wandered. In word clouds! In case you were wondering what Glenn Beck's mind looks like, here you go:

I have to say I prefer its zany zig-zags to Hannity propaganda.

Yes, support for ending Prohibition is slowly growing though still doggedly without majority support. One reason:

In the CNN poll, non-whites were less likely to support legalizing marijuana than whites, even though, as the Human Rights Watch has reported, blacks will more likely be arrested for drug possession than whites (the CNN poll did not break down the "non-white" category further because the sample sizes would be too small).

The Trig story reaches its denouement.

Weigel reprints a bunch of tweets from the Palinites complaining that Palin's Madison speech was not covered extensively enough. It's particularly amusing given the complaint about Jennifer Rubin, about as big a Kool-Aid drinker on the far right as you can find. You can see this as desperation for a fading reality TV star; or as an attempt to reboot her flagging presidential bid. I suspect the latter.

Ben Adler reviews Suleiman Osman's The Invention of Brownstone Brooklyn:

Often ethnic diversity is a product of earlier waves of gentrification. Many of the first people to buy Brooklyn rooming houses and turn them back into one or two family homes were West Indian immigrants. And, as Osman explains, it was the college-educated sons of Irish Park Slope and Italian Carroll Gardens who eschewed moving to the suburbs with their cohort in the early 1960s. Instead they organized local businesses, homeowners, and newcomers to renovate, beautify, and promote their neighborhoods. But it is exactly these elderly minorities and white ethnics who are replaced by each yuppie couple.

Charli Carpenter repeats an oft-cited reason to end Afghanistan's war on drugs, much needed pain relief in the developing world:

[T]he need for analgesics like morphine far outweighs the available supply. In part, this is due to the fact that such analgesics are produced from opium, the sap of the poppy. Since the same plant extract can also be used to produce heroin, a significant amount of political effort is now being expended worldwide to actually inhibit, rather than encourage, opioid production. This fuels shortages of analgesics.

Jeremy Cherfas offers another aspect to consider:

One thing [Carpenter] doesn’t mention — and why would she? — is that poppies would probably be a lot more sustainable than most of the alternatives, needing less water and less land than, say, wheat or vegetables, and almost certainly displacing less local agricultural biodiversity.

(Photo: An opium poppy farmer watches as U.S. Army troops pass through his field shortly before a firefight with Taliban insurgents on March 14, 2010 at Howz-e-Madad in Kandahar province, Afghanistan. By John Moore/Getty Images)

A reader writes:

The issue with Kleiman's take, as I see it, goes back to the classic argument with organized crime – is it less of a blight on society when power is centralized or when it is de-centralized? If the scenario he proposes plays out, it will not lead to more restraint among rival cartels, I fear, but less restraint; you’ll have smaller, ambitious groups willing to escalate violence in order to fill the power vacuum and establish their reputations. In fact, some sources allege this has already happened in the wake of Mexico’s successful attacks on some of the major cartel players. Here's what STRATFOR writer Scott Stewart said in regards to Mexican President Felipe Calderón's attempt to break up the cartels:

This weakening of the traditional cartels was part of the Calderon administration’s publicized plan to reduce the power of the drug traffickers and to deny any one organization or cartel the ability to become more powerful than the state. The plan appears to have worked to some extent, and the powerful Gulf and Sinaloa cartels have splintered, as has the AFO. The fruit of this policy, however, has been incredible spikes in violence and the proliferation of aggressive new drug-trafficking organizations that have made it very difficult for any type of equilibrium to be reached. So the Mexican government’s policies have also been a factor in destabilizing the balance.

And don’t underestimate the importance of reputation and violence in the narcotrafficante underworld. The celebrated HBO series The Wire did a masterful job of illustrating the pushback that reformers in the drug world, who want the money but not the violence, get from their peers. Or you can take any number of anti-gang activists who are murdered by their old colleagues for trying to reform the “system” of the criminal underworld. As fascinating as a “race to the bottom” sounds as a strategy for violence – and I'd support the attempt – it probably will only increase the violence.

Another writes:

While I can appreciate the need for new ideas in the drug war, Kleiman's isn’t one. There are four main difficulties with this plan. First, and most obvious, would be the rise “false flag” missions. Violence wouldn’t stop – it would just be done in such a way to put blame on rival cartels.

Second, Mexican cartels control and battle over geographic areas. So if Mexico and the US were to put all their resources towards the dismantling the Zetas, for example, that would leave the Gulf cartel free to continue to import through Texas and into the Central and Eastern US. And even worse, the flow of narcotics into the Western US by the Sinaloa and Tijuana cartels would be left unaddressed and unabated.

Third, dismantling a cartel takes time. Mr. Kleiman writes off this difficulty as saying dismantling a cartel is “not hard, in a competitive market” without explaining what he means, or why he believes this will be easy to accomplish. While it is true that cartels are often run like business organizations, a cartel under attack would quickly fracture. It might re-organize. It might join forces with other cartels. It’s members might defect. How would we define whether a cartel has been “dismantled?” When its known leader is arrested? By that time, the problem would just shift to a new name or location. Regardless, even with the whole of our efforts, it would likely take years, not months, to fully dismantle just one cartel by any definition.

Fourth, and most important, this plan depends on the efforts of the Mexican government more so than the US. It is no secret that the Mexican government and police forces are highly corrupt at all levels. So unless and until Mexico is willing (and able) to fully devote its resources to defeating the cartels, any of these high-minded, idealistic plans are doomed to failure.

But I do give Mr. Kleiman credit for proposing an idea that doesn’t fall back on the tired mantra of “legalize it.”

David Sirota takes aim at Newsweek's current cover story:

To be sure, many individual white males have been hurt by past recessions, and many more have been hit hard by this one, too. But the obsessive and disproportionate focus on the plight of this particular demographic actually contradicts the underlying theory of white victimhood. Far from being "forgotten," persecuted or "without a freakin' prayer," white men still very much retain their cherished privilege, so much so that their problems are presented by the media as the most pressing national emergency — even when, on the whole, white men still occupy a comparatively enviable position in our economy.

Choire Sicha does some math:

There are about 154 million Americans in the civilian labor force. About 140 million of them are employed. About 114 million of those employed are white people. White men who are older than 16 have 61 million of the jobs. So white men have 43% of all jobs, while white men make up about 36% of the U.S. population. White women 16 and older have about 53 million of the jobs (37%—about proportionate). That's already 114 million of the jobs (81% of all civilian jobs), leaving just 26 million jobs.

So there are about 15 million black people with civilian jobs in the U.S. (out of about 40 million black people in total), leaving 11 million jobs for the Asians and "Hispanics" and the "everyone else"—and the Asians have like 7 million of those.

(Photo: Fedrik Broden for Newsweek.)

Steve Kornacki tells cocksure Democrats to wake up:

Well into 1992, even as economic anxiety was soaring and unemployment was approaching 8 percent (a significant jump from the start of his presidency), George H.W. Bush was still seen as a good bet for reelection because of the supposed weakness of that year's Democratic field. Eventually, Democrats settled on Bill Clinton, who finally pulled ahead of Bush in July — and then never looked back. (Note: Ross Perot had nothing to do with Bush's defeat that November; it was the economy that sunk the president.) Rest assured, if the economy doesn't improve — or gets worse — the GOP will be well-positioned to oust Obama in 2012, provided the party doesn't nominate a fringe candidate.

Kay Steiger wonders why there are so few films on women with disabilities:

Though not super common, stories about a protagonist overcoming the complications of a disability are getting some attention, what with the Oscar-winning The King's Speech. … But what you don't see in these types of stories are female protagonists. An obvious candidate for a story like this would be a biopic of deaf-and-dumb heroine Hellen Keller, but no such major film adaptation has been done, save a documentary about her released in 1954.

The recent Temple Grandin flick is an exception to this rule.