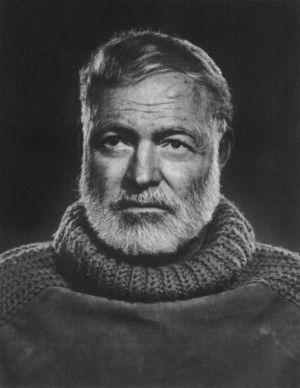

Deborah Jerome considers the time it takes for mourners to return to society:

We want to acknowledge the griever’s pain, because we also know it as our own. We offer our hand, our clumsy platitudes, a cup of broth. But at some point we itch to move on to our lives, and leave the mourner to move on to his or hers. Not out of callousness, but out of the knowledge that in the end, grief is a lonely and entirely personal place. What we wish for the grieving is that they learn to pull away from the wild, unruly currents of mourning and rejoin us, knowing that nothing we say can really matter, because we know grief’s dark allure. In grief we sound the depths of our love. In that regard, it’s a private privilege. Society has no place there.