Another wonderful homage to Carl Sagan's Pale Blue Dot, by Adam Winnik:

Pale Blue Dot – Animation from Ehdubya on Vimeo.

Another wonderful homage to Carl Sagan's Pale Blue Dot, by Adam Winnik:

Pale Blue Dot – Animation from Ehdubya on Vimeo.

Thomas Powers reads Mark Twain’s autobiography. Twain’s response after hearing of a friend who died a violent death:

‘What was he born for?’ Twain asks silently at the dinner table. ‘What was his father born for? What was I born for? What is anybody born for?’ Twain does not answer these questions, just as he declined to show us the fate waiting for Huck and Jim down the river. But Twain’s late writings hammer out a harsh law of life, the thing he believed at the end. It comes down to this: life is in cruel balance, every good thing shall be taken away and missed until the final hour, the things that make life sweet are the things that make life hurt. Twain lays it out for anybody to see, but he will not say it.

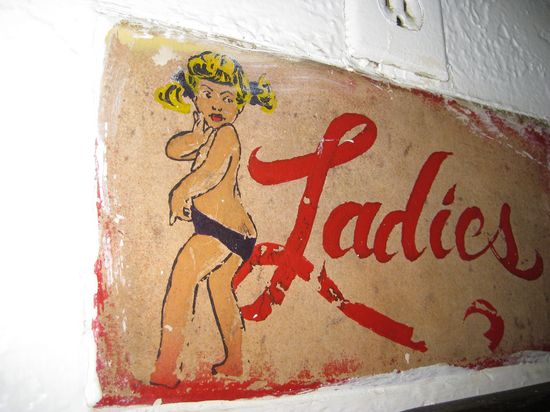

Jens Liljestrand ponders the line between photography and child pornography. Sanna Rayman argues against overreacting:

Just as we don't want to hand victory to terrorists by creating a repressive society, we don't want to hand victory to pedophiles. If we always look out for risks we will start to look at things in a different way. Our first thought when we see a nude child is "What would a pedophile see" instead of "What am I seeing?" And then we've already given up part of our own worldview. Something that didn't use to be a problem becomes something inappropriate.

(Photo by Flickr user Elizabeth Herndon)

Kowloon, Hong Kong, 9.30 am

John Horgan discounts the "warrior gene" and the larger trend of behavioral genetics, which spawned the gay gene, the God gene, the high-IQ gene, the alcoholism gene, the gambling gene and the liberal gene:

Unlike, say, multiverse theories, unsubstantiated claims about human genetics can have real-world consequences. Racists have seized on warrior gene research as evidence that blacks are innately more violent than whites. In 2010 defense attorneys for Bradley Waldroup, a Tennessee man who in a drunken rage hacked and shot a woman to death, urged a jury to show him mercy because he carried the warrior gene. According to National Public Radio, the jury bought this "scientific" argument, convicting Waldroup of manslaughter rather than murder. A prosecutor called the "warrior gene" testimony "smoke and mirrors." He was right.

“Could Have,” by Wislawa Szymborska, translated from the Polish:

It could have happened.

It had to happen.

It happened earlier. Later.

Nearer. Farther off.

It happened, but not to you. …You were in luck — there was a forest.

You were in luck — there were no trees.

You were in luck — a rake, a hook, a beam, a brake,

A jamb, a turn, a quarter-inch, an instant …

C.J. Chivers has the full poem, in honor of Chris Hondros and Tim Hetherington:

Every so often you read a poem — or a book, a passage, a play, a transcript —that makes you wonder why you trouble to write. This is because you understand, long before you finish reading what is in your hands, that you will never match what is before your eyes, and ringing in your mind.

Michael Ware also remembers the photographers.

(Photo: Photographers Chris Hondros (left) and Tim Hetherington at work this week in Misrata, Libya. By Getty Images (left); Phil Moore / AFP-Getty Images)

Dan Ariely reserves praise for buying dumb products, even in a future where celebrities might shill for bottled air:

Consider for a moment a world without marketing hype. One in which there’s nothing you really desire beyond what you need to live. … The line is narrow, indeed, between being motivated to work and mortgaging the future (both your own and society’s) to get stuff like bottled air. Still, as we continue to redefine capitalism, let’s not discount the role of aspiration and the desire for incremental luxuries–things we want but don’t necessarily need. They can fuel productivity and thus have a valuable function in our economy.

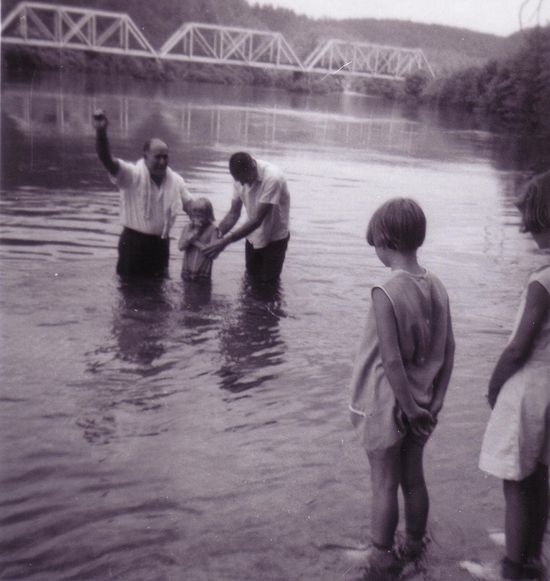

Stefany Anne Golberg reflects:

To see a person walk fully clothed into water, becoming heavy and vulnerable in nature, weighed down by corporeality — it’s an almost mythological sight, evoking Ophelia as much as Moses and Jesus. It is an act that immediately makes us think of drowning, just as the emergence of that same person walking slowly, drenched, gasping a little, up through the mud makes us thinks of survival. Of salvation.

(Photo by Flickr user superbomba)

Kathryn Schulz delights in Sarah Bakewell's How to Live: or, A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer:

Montaigne would not countenance torture (he couldn’t even stomach hunting) and, unusually for his era, he spoke out against it. It was, he felt, both strategically and morally flawed. Most torture victims, he reasoned, would say anything to put an end to pain; moreover, torturing someone on suspicion of wrongdoing was “putting a very high price on one’s conjectures.” As the terrorism of France’s religious wars intensified in the region of his family home, Montaigne refused to guard the doors of his estate. To do so would have been to capitulate to violence and, in a sense, to escalate it. He chose, instead, to live out the counsel of the Mishnah: “Where there is no human being, be one.”

It is this quality that has made Montaigne a hero to so many opponents of fanaticism. And it constitutes one of his greatest answers to the question of how to live. As Bakewell distills it: “Be convivial.” In that blithe-sounding word, she helps us hear solemn undertones. Be convivial: live with one another, be on the side of life, forbear. Even as the long party rages on, she reminds us, a long war rages just outside the door. Montaigne’s joy in humanity was not a way of ignoring it, but a way of resisting it.