Chris Beam recounts its history:

There are legitimate reasons for a perp walk, aside from humiliation. If a defendant may have committed other crimes, police might want to broadcast his name and face to get other victims to come forward. A prosecutor may also opt for a perp walk if a suspect is considered a flight risk.

Instead of simply issuing a court summons, law enforcement conducts a surprise arrest and invites the press. "It helps them with the bail argument," says Ryan Blanch, a criminal defense attorney in New York. "If [the prosecution] wants to argue for no bail, they can say, we had to rip him from his house." It also makes running away harder, if they do get out on bail.

Whatever the rationale, perp walks have become as much a staple of the U.S. criminal justice system as the Miranda warning. They've been ruled constitutional, so long as they serve a legitimate law enforcement purpose.

Sam Roberts also digs up some facts:

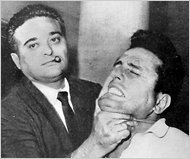

In 1962, Capt. Albert A. Seedman, who later became the city’s chief of detectives, was  reprimanded for staging a perp walk after photographers missed the original one and, worse still, propping up the accused murderer’s chin to capture him full-face. In 2000, a federal appeals court in New York ruled in the case of a doorman accused of robbing an apartment that perp walks staged solely to accommodate the news media violated a the defendant’s constitutional rights against unreasonable search and seizure. The same court ruled later in another case involving a correction officer, though, that while a defendant might claim a privacy interest in not having himself publicly humiliated, “that privacy interest was outweighed by the county’s legitimate government purposes.”

reprimanded for staging a perp walk after photographers missed the original one and, worse still, propping up the accused murderer’s chin to capture him full-face. In 2000, a federal appeals court in New York ruled in the case of a doorman accused of robbing an apartment that perp walks staged solely to accommodate the news media violated a the defendant’s constitutional rights against unreasonable search and seizure. The same court ruled later in another case involving a correction officer, though, that while a defendant might claim a privacy interest in not having himself publicly humiliated, “that privacy interest was outweighed by the county’s legitimate government purposes.”

The case against the perp walk here.

reprimanded for staging a perp walk after photographers missed the original one and, worse still, propping up the accused murderer’s chin to capture him full-face. In 2000, a federal appeals court in New York ruled in the case of a doorman accused of robbing an apartment that perp walks staged solely to accommodate the news media violated a the defendant’s constitutional rights against unreasonable search and seizure. The same court ruled later in another case involving a correction officer, though, that while a defendant might claim a privacy interest in not having himself publicly humiliated, “that privacy interest was outweighed by the county’s legitimate government purposes.”

reprimanded for staging a perp walk after photographers missed the original one and, worse still, propping up the accused murderer’s chin to capture him full-face. In 2000, a federal appeals court in New York ruled in the case of a doorman accused of robbing an apartment that perp walks staged solely to accommodate the news media violated a the defendant’s constitutional rights against unreasonable search and seizure. The same court ruled later in another case involving a correction officer, though, that while a defendant might claim a privacy interest in not having himself publicly humiliated, “that privacy interest was outweighed by the county’s legitimate government purposes.”