An NRO editorial claimed no. Jonathan Cohn counters:

When you make people pay more for medical care, they consume less of it. This was the basic insight of the Rand Health Insurance Experiment, which most economists consider the gold standard for this sort of research, and countless studies since then. Conservatives should know this as well as anybody, since the whole point of consumer-directed health care – the approach they generally favor – is to increase cost-sharing so that people will use fewer services and wares, thereby spending less money. Of course, the problem with higher cost-sharing (and the reason folks like me are wary of it, depending on the details) is that it can discourage use of medical care that’s beneficial. Studies have shown, for example, that seniors react to higher cost-sharing on prescriptions by cutting back on their hypertension medicine. That’s bad medicine, because it increases the likelihood they’ll get a heart attack or stroke. That’s also bad economics, because heart attacks and strokes are incredibly expensive to treat.

He cites multiple studies that followed free family planning services for low-income women in California, including one published in the American Journal of Public Health:

Family PACT contraceptive services provided in fiscal year 1997–1998 are estimated to have reduced the total number of births in California by 7% to 8% in the fiscal year 1998–1999 … The reduction in births also reduced public expenditures for health care, social services, and education for these women and for their children. … averting 108,000 pregnancies saved the federal, state, and local governments more than $500 million at a ratio of $4.48 saved to every dollar expended on family planning services.

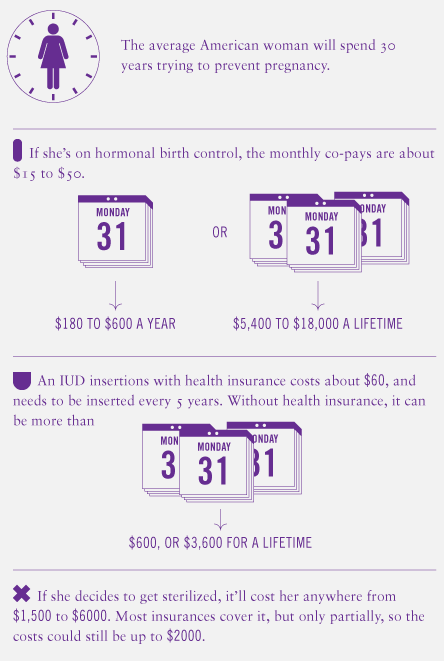

(Image: Partial view of a infograph by GOOD)