by Zoë Pollock

Mark Vernon questions the merits of Buddhism as interpreted by the West:

[I]n meditation, Buddhism offers a therapy that tackles the hyper-individualism of today by stressing the instability and dissolution of the self. Only, it seems to me that is not true. Whilst it may be very hard to say what an ‘I’ is – and it is surely multiple and porous – it is foolish to rush to concluding there’s no ‘I’ at all. It is less reactionary, surely, to rest with the notion that we are something of a mystery to ourselves – a mystery deepened in meditative analysis, not dissolved in it.

As a Jew who joined the Buddhist/meditation club in college for the cute boy who chaired it and the free retreat to Cape Cod, I'm not qualified to speak to the religious aspect. But Josh Rothman, summarizing philosopher Owen Flanagan's book The Bodhisattva's Brain: Buddhism Naturalized, does a good job refuting Vernon:

In the Buddhist world, materialism and determinism can be morally informative. First, they suggest that we aren't as important or permanent as we think we are — that, in a fundamental sense, our selves or souls don't really exist in any lasting way (a conclusion, incidentally, shared by Western philosophers like John Locke and Derek Parfit). This, in turn, suggests that satisfying our own personal needs and wants shouldn't be our number-one priority; instead, we should focus on projects that benefit everyone, and work to become more kind and generous to our fellow human beings.

Some behaviors that appear selfish can make us better in and to the world.

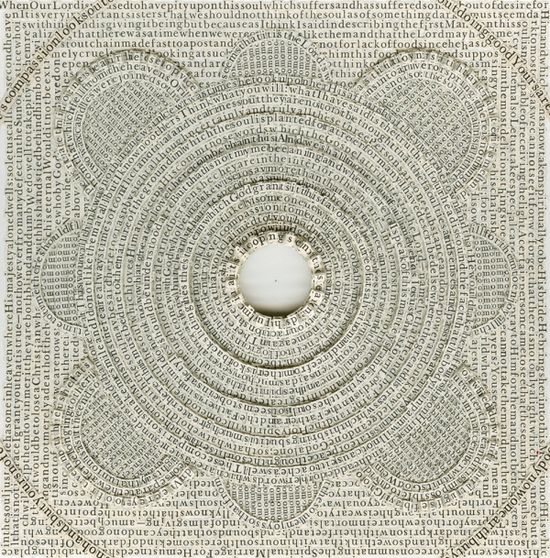

(Image: From Mantras & Meditations by Meg Hitchcock, who describes her work, "I may cut up a passage from the Old Testament of the Bible and reassemble it as a passage from the Bhagavad Gita, or I may use type from the Torah to recreate an ancient Tantric text. A continuous line of text forms the words and sentences in a run-on manner, without spaces or punctuation, creating a visual mantra of devotion.")