Matt Steinglass joins the debate over Palestinian statehood:

The PA move to ask for statehood may be a mistake. The Israeli move to reject it may be a mistake. But if the UN votes to recognise statehood, the American rejection of that result will also be a mistake. It will severely damage America's aspirations to improve its standing in the perhaps-democratising Arab world. It will undercut America's ability to broker an eventual stable peace deal. It will delay Israel's necessary acknowledgment that it cannot hold out against the Palestinians forever. It may provoke a new intifada. It's conceivable that it could incite terrorist attacks and cost American lives. And if Congress does cut off American aid to the PA, it will yank the rug out from the president and State Department and call into question whether America can live up to its promises, or conduct a coherent foreign policy on this issue at all.

Larison is still against the idea:

Millman is probably right that Palestinians in the diaspora won’t be materially harmed by recognition, but for many of them that it isn’t the point. This might remove an obstacle to a negotiated settlement, but the statehood bid is itself an acknowledgment that such a settlement is not forthcoming. In this case, it is the abandonment of an important symbolic position in exchange for nothing. Maybe somewhere down the road it “opens the path to actual, material progress,” but that must seem to be almost as much of an illusion as the “right of return” is.

James Wimberley differs:

The new state will continue to have a bitter dispute with its neighbour Israel over borders, settlements, Jerusalem as the capital, free movement, water, and refugee return: exactly the same disputes that the Palestinian Authority has now. Can anybody explain to me why Palestinian statehood makes these disputes more intractable? And it would clear the air by removing the non-issue of state recognition from the table.

Yglesias doesn't understand Israel's myopia:

Ever since the unilateral declaration issue was floated, I've been gobsmacked by the lack of Israeli creativity around this issue. Why not spend the past year seeing this as an opportunity to force the Palestinians to make a clear statement of what borders they're claiming? Or to try to get the United States to forge a compromise in which we agree not to veto a resolution if the Arab League will agree to finally extend diplomatic recognition to Israel, thus turning the Palestinians into lobbyists for a pro-Israel measure?

Goldblog seconds him:

A creative Israeli prime minister could have jiu-jitsued this resolution, and turned it into a call for the members of the United Nations to formally declare their understanding that Israel, within its 1967 borders, is the nation-state of the Jewish people. But Netanyahu is a prisoner of a minority of the Israeli polity that has made continued possession of the West Bank more important, in some ways, then the preservation of Israel as a Jewish-majority democracy.

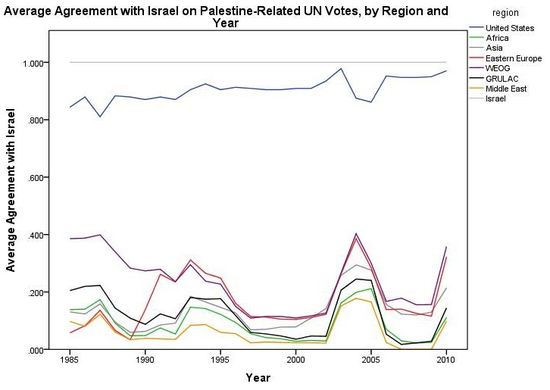

Chart from Erik Voeten, who captions:

[D]isagreements [over Palestinian issues] have been a structural feature of global politics for some time. What has changed then, are not so much the preferences of states but the relative power and resolve of those states most supportive of Palestine. States like China, India, and Turkey have grown much more powerful in relative terms over the past decade. Moreover, domestic changes in Turkey and much of the Arab world have given leaders greater incentives to take more risky actions in support of the Palestinian cause.