A reader writes:

Jesus said, "The poor you will always have with you." The US Census Bureau has effectively made this public policy by defining poverty as a function of the average income level. People have argued for a long time about whether this approach is the right one (linen shirts, and all that). But in any case, it renders discussions about whether the numbers of poor are rising or falling a bit meaningless.

Another writes:

I was a bit surprised by what you chose to include in your post on the Census Bureau's release of increased poverty indicators. By summarizing Wilkinson's point but not Drum's, the portrayal of the indicators' inadequacy is quite one-sided.

The flaw the Wilkinson article, compared to the Drum article, is that the official poverty rate indicators already underestimate the high costs of living that contribute to poverty. Wilkinson notes that "the poverty line is set [rather arbitrarily] at three times the food bill of a typical family in the early 1960s, adjusted for inflation. It is possible to complain about the adequacy of this way of fixing the poverty line, but let's leave it alone." Leave it alone? When as Drum notes, "official poverty thresholds developed more than 40 years ago do not take into account rising standards of living or such issues as child care expenses, other work related expenses, variations in medical costs across population groups, or geographic differences in the cost of living"?

While I do agree that poverty indicators should account for the impact of programs like Section 8, food stamps, Medicaid, and the Earned Income Tax Credit (perhaps with side-by-side figures for the poverty level "before and after" these sources of assistance, which would provide some outcome indicators for these programs' effectiveness), they should also account for the actual costs of maintaining a minimum standard of living in different localities. The last point is key, since after all $20,000 a year might well be able to minimally feed and house a family of four in rural Nebraska, but not in urban Washington, DC or New York City, where the cost of living is exponentially higher.

A more accurate measurement is needed, and I'll look forward to seeing the soon-to-be-released proposal Drum mentions. Whether intentionally or not, by citing Wilkinson's point and not Drum's you came off as echoing the Heritage Foundation's continued insistence that the increasing affordability of (used) home appliances somehow means that people aren't "really" poor.

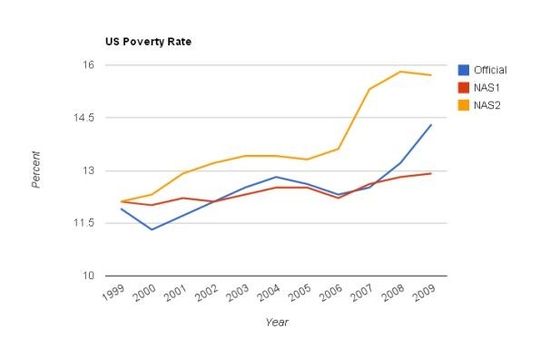

Suzy Khimm chimes in by showing how the Obama administration has developed a model that is likely to show even higher rates of poverty (even when you factor in things such as food stamps and EITC, as Wilkinson recommends). She captions the above chart:

The yellow line (NAS2) shows that poverty is significantly higher than the official rate. But the red line (NAS1) is mostly lower. What’s responsible for the difference? Both experimental rates factor in the benefits of public assistance, as well the cost of out-of-pocket medical expenses, work transportation, etc. But the lower rate is adjusted to the Consumer Price Index, while the higher rate is based on the Consumer Expenditure Survey–an average for actual consumer spending on food, clothing, utilities, and shelter by those at the 33rd percentile of income.

Another reader:

Regarding the photo you used: I think it subtly contributes to the errant stereotype that poor people sit around doing nothing all day. In truth, most poor people are busy the whole day working to try to keep themselves and their families from becoming more poor. I would suggest you find a photo instead that illustrates one of the working poor racing out the door at the end of the shift from his first job to make it to his second job on time, or of a working mother rushing to drop her kids off at daycare so she doesn't miss the bus that will take her to work, or that same mom, with tired hungry kids on her lap, on the bus on the way home at the end of the day. How about farmworkers stooped over in the setting sun, or nursing home aides standing on swollen feet at the end of a double shift? There are plenty of poor people in America, and most of us don't sleep on the street.