by Zack Beauchamp

Anne-Marie Slaughter wrote a provocative article last week heralding the era of a new version of sovereignty:

Fred Kaplan, in an otherwise excellent piece on humanitarian intervention in Slate, says that the responsibility to protect (R2P) is just a sanitized version of humanitarian intervention. Not so, in my view. For the first time, international law and the great powers of international politics have recognized both the rights of citizens and a specific relationship between the government and its citizens: a relationship of protection. The nature of sovereignty itself is thus changed: legitimate governments are defined not only by their control of a territory and a population but also by how they exercise that control. If they fail in that obligation, the international community has the responsibility to protect those citizens.

Joshua Foust countered yesterday. I respect Josh a great deal (partly as a result of frequent conversations on this issue over Twitter), but I think he gets it fundamentally wrong here. The in-principle case against R2P is, in fact, extraordinarily weak.

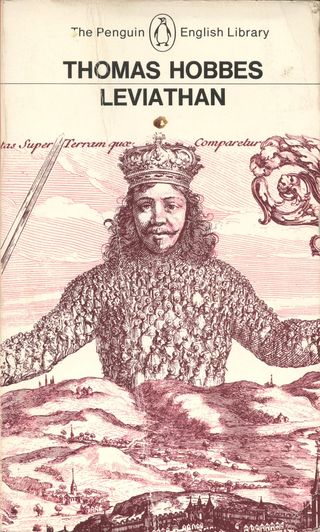

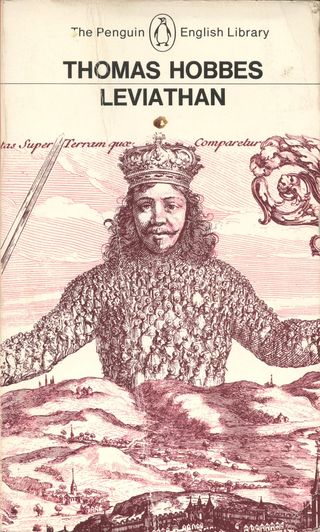

The argument begins by defining sovereignty as:

he concept of a state (i.e. its government) having complete, independent authority over its territory. The concept of viewing both governments and societies as “subjects” of international law is a fairly new one, though in the realm of international law it’s been a fundamental assumption for some time. At the same time, Slaughter’s redefinition of “intervention,” based on the idea that there is no such thing as traditional sovereignty, is a brand new way of glossing over the thorny problems that undermine a policy of humanitarian intervention.

But Slaughter's argument was never that "sovereignty doesn't exist:" it's that sovereignty as  generally understood is a morally deficient idea. We only endorse the idea that states have rights because accepting the idea that they do is good for individual rights. There's no way to harm a state other than harming its people. In fact, the entire justification for states existing in the first place is that they're guarantors of individual rights and well-being. Thus, we should only endorse the idea that states have "complete, independent authority" over their territory if we think that a system like that is actually good for the world's citizens.

generally understood is a morally deficient idea. We only endorse the idea that states have rights because accepting the idea that they do is good for individual rights. There's no way to harm a state other than harming its people. In fact, the entire justification for states existing in the first place is that they're guarantors of individual rights and well-being. Thus, we should only endorse the idea that states have "complete, independent authority" over their territory if we think that a system like that is actually good for the world's citizens.

Note that this, not the idea of humanitarian intervention, is the core of R2P as a doctrine. R2P is simply the idea that a state's right to sovereignty is contingent on that right best serving its citizens. When states murder their own people or starve them to death, that state gives up the justification for having the right to sovereignty in the first place. R2P does not require military intervention in every case where this happens – it merely argues the international community has a duty to help the people who are being failed by their state. That's the "responsibility" in R2P and, as Steve Hynd argues in his reply to my earlier post, that can be fulfilled by assistance as well as arms.

That's the core problem with Josh's argument that "it is that very sovereignty which also creates the moral and legal justification to intervene." Nope. The legal justification to intervene came from the U.N. Security Council.* The moral justification was that Qaddafi had forfeited his right to sovereignty by killing his own people. It has nothing to do with domestic sovereignty.

This moral analysis helps answer Josh's core charge:

My biggest objection to the new doctrine of interventionism is that it seem to rely so much on whim. I still don’t understand why we needed to intervene in Libya, but not Yemen and Syria.

I repeat the answer to this question a lot, but it's important: just. war. constraints. Only a straw man version of R2P-justified interventionism says "we must intervene EVERYWHERE bad things are happening!" We are constrained from intervening in some places because we thinks the moral costs related to intervening would be higher than the benefits. Intervention is justified by reference to R2P, not vice-versa. It's not at all clear what NATO could do to help in Yemen and Syria given 1) the distinct character of the conflicts there, 2) its already-overexteded forces and 3) political roadblocks. It's a truism in morality that "ought implies can" – we don't have an obligation to do things that we, in fact, can't do. Interventionism doesn't require blindly ignoring costs or tradeoffs. It requires deploying resources when, according to one's judgment, they can do the most good. Just because it's an idea that requires contextual judgments doesn't mean its inconsistent.

Josh also talks a lot about whether the Libya intervention was a bad idea. He may or may not turn out to be right (you can guess what I think), but his comparisons to Iraq doesn't at all help his case. First, we were far more prepared for the post-war situation than in Iraq. Second, the relevant point of comparison for an argument about sovereignty isn't that both interventions were in a sense preemptive – it's that Iraq was principally justified not on humanitarian grounds, but on traditional self-defense grounds. Powerful states can always manufacture reasons to go to war if they're willing to bear the costs. History suggests the erosion of sovereignty caused by accepting rules like R2P isn't going to lower said costs to any significant degree.

Further, Slaughter's general case for weakening traditional sovereignty rights in favor of an R2P-like conception doesn't rest on the Libyan War's shoulders. In fact, she only mentions Libya twice in her piece. Her argument that "in the 21st century populations are often at equal or greater risk from their own governments as they are from other states" is the core claim here, and that's almost certainly true. There are far more civil wars than state-to-state wars today, and the former have, in recent years, killed many more than the latter. That's to say nothing of things like genocide and state created famine I discussed in my last post. Under the traditional conception of sovereignty, U.N. peacekeeping operations (which have been quite effective [pdf] in mitigating these problems) would be impermissible unless the warring party that was nominally the government consents. Even aid couldn't be let in without their say-so. Do we seriously think an absolute right to sovereignty ought to be defended at these costs?

Josh may turn out to be right that the Libya intervention was a mistake. That depends on the specific circumstances at play in that case. But that's no reason to defend an antiquated, incoherent notion of absolute sovereignty that's more than past its expiration date.

*Though Josh mentions that the legal authority domestically came from sovereign political structures, I don't really see what's relevant about that point.

(Photo via flickr user scatterkeir.)

Thom Lambert

Thom Lambert

generally understood is a morally deficient idea. We only endorse the idea that states have rights because accepting the idea that they do is good for individual rights. There's no way to harm a state other than harming its people. In fact, the entire justification for states existing in the first place is that they're guarantors of individual rights and well-being. Thus, we should only endorse the idea that states have "complete, independent authority" over their territory if we think that a system like that is actually good for the world's citizens.

generally understood is a morally deficient idea. We only endorse the idea that states have rights because accepting the idea that they do is good for individual rights. There's no way to harm a state other than harming its people. In fact, the entire justification for states existing in the first place is that they're guarantors of individual rights and well-being. Thus, we should only endorse the idea that states have "complete, independent authority" over their territory if we think that a system like that is actually good for the world's citizens.