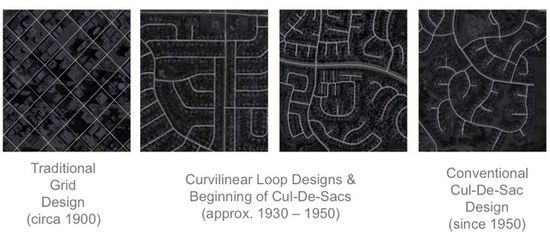

In urban design, Emily Badger defends the grid system:

Most of the oldest cities in America – not to mention the oldest capitals in Europe, or in the Roman Empire, for that matter – were laid out in neat, densely interconnected grids that enabled people to get around before cars came along. Manhattan looks like this. So does Savannah, New Haven and Washington, D.C. … Americans lost sight of that tightly knit model when we got into cars and began to envision something else: the Garden City.

Felix Salmon nods:

Shorter distances mean that you’re more likely to walk or bike; they also make the neighborhood feel smaller. For many decades, suburbia was designed on the idea that Americans want to feel as though they’re far away from each other, but the fact is that we need community and linkages just as much as we need a space of our own.