A reader expands upon a phenomenon broached in a previous post:

It should be noted how the National Anthem is treated before Chicago Blackhawks home hockey games. While the anthem is generally sung in a manner best described as "triumphant," the fans in the stadium cheer loudly throughout the entire anthem, flying in the face of the idea of "hushed reverence", sometimes coming close to completely drowning out the singer. It is actually pretty controversial in the sports world (a lame Fox News debate can be found here), but it has remained a tradition in Chicago since the 1980s.

A reader points to the above video:

There was controversy last year during the NFL playoffs when Chicago fans cheered throughout the National Anthem sung by Jim Cornelison. (What surprised me is how many people kept their hat on.)

Some remaining renditions suggested by readers:

Don't know if you have heard this one yet. In 2004, Bruce Springsteen and other liberal rock stars organized a sprawling, coordinated tour of various swing states to register voters, mobilize the base, and stump for Kerry-Edwards. You know the outcome, but Bruce's rendition of the anthem endures. He opened every show with this pensive, chiming instrumental before transitioning into an angry, hard-hitting "Born in the U.S.A." Without singing a note, he cuts through the din of shrill anti-war lefties and smug neoconservative apologists, conveying both the outrage at America's misadventure in Iraq and the unyielding love for his country.

Another:

Please don’t forget this beautiful three-part harmony version of the Star Spangled Banner, sung by those America-hatin’ Dixie Chicks.

Another:

Not sure if any readers have pointed to Jack Ingram, but his versions during last year's NBA Finals and this year's ALCS were lovely. Nice to see some understatement in Texas, don’t you think?

Another:

I simply have to weigh in to this great thread with one of the more unique and "out of left field" renditions I've heard, not as much due to the rendition itself, which is pretty good and unlikely to offend, but due to the singer: none other than Jerry Stackhouse, a professional NBA basketball player. I grew up in Detroit and went to college during the years he played for the Pistons, so I knew the brother could sing (he often did the Anthem for home games), but it was always fun to watch the amazement/amusement of other players, media and spectators when they announced who the singer was. Stack hardly looks the part of a crooner, but his rendition, which draws heavily from gospel choir stylings and R&B, is I think really beautiful – especially his inspired riff on "gave proof through the night".

Another:

This one always gets to me. It was Disability Awareness day at Fenway Park and they had a young man sing the Anthem. He got a bit nervous in the middle, so the fans helped him out. I love the crescendo as the fans realize what's happening and voices are added to voices, and the gracious and proud cheer at the end.

Another notes:

The young girl who flubbed the National Anthem, Natalie Gilbert, got a web redemption eight years later on Tosh.0.

One more:

The Hendrix quote about his rendition of the Star Spangled Banner being "beautiful" comes from an appearance he did with Dick Cavett. I think Jimi's words on the matter sum up this entire thread.

The whole National Anthem thread here, here, here, here and here.

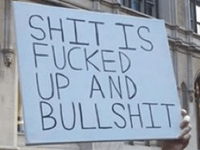

around the country, on Facebook and at protests, people are

around the country, on Facebook and at protests, people are