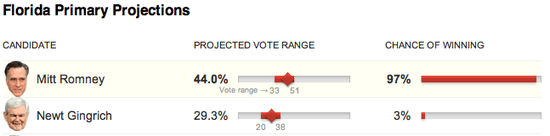

Nate Silver provides a forecast. In another post, he sorts through various recent polls:

[I]f Mr. Gingrich has some slim chance of winning, there’s also the chance that he could lose by 25 or more points. But they’re not where the balance of the evidence lies. Odds are, instead, that Mr. Romney will win by somewhere in the range of 10 points to 20 points, meaning that many networks are likely to declare him the winner shortly after polls close.

Charles Franklin's projections:

The end result is the standard trend putting Romney at 39.7 and Gingrich at 31.7, with Santorum at 11.5 and Paul at 10.2.

Mark Blumenthal adds:

[R]emaining voter uncertainty combined with the wide discrepancies among some of the polls is a warning that small variations in polling methodology can make a big difference in the results. Thus, while Mitt Romney appears headed for a Florida victory on Tuesday, his ultimate margin may still surprise.

Romney may have taken a slight risk with going so full-bore in Florida, as far as expectations are concerned. Let's say his margin of victory is 5 points – 40 – 35. I'd say the news coming out of the state would not be that damaging to Gingrich, especially given the 5 – 1 advertising disadvantage he has had to counter.

Of course, if Romney does better than current expectations (by which I mean, given this zig-zagging race, the last three days), the reverse applies. But it's worth remembering that Florida only has 50 delegates this year – because it was penalized by moving its primary up. The Maine and Nevada caucuses provide more delegates combined. I hope you're sitting down because I agree with Sarah Palin. This thing should continue beyond the moment one candidate gets 100 delegates out of the 1,144 he needs to win. In very few contests, would you call the winner after four out of fifty rounds.

We'll be live-blogging for as long as it stays interesting.