Christopher Caldwell studies it:

[S]o big and rich is Germany—particularly now that reunification has brought its population to 80 million—that joining it in anything means playing by its rules. This is not Germany’s fault. It is the classic “German problem” that has confronted Europe for the whole modern era. It was camouflaged for six decades only by Germany’s reluctance to express any wishes whatsoever.

As long as Germany wasn’t complaining, others could make free with Germany’s credit card. Once in the euro, Greece, Italy, Spain, and other countries that bankers used to consider reckless or unstable could borrow at the same rates. (The treaties that bound all these dissimilar countries together stipulated that there would be no bailouts for those who borrowed too much, but bankers obviously didn’t believe that.) A boom in lending pushed up wages and prices in those “peripheral” countries, rendering them uncompetitive. After the financial crisis of 2008, the countries that had overborrowed were saddled with more debt than they could comfortably repay. The eurozone’s Mediterranean members have come to think that Germany ought to rescue them. But the Germany to which they are addressing their petitions is not the penitent, diffident, and easily browbeaten land that they came to know over the last three generations. Germany has its own ideas about economics and morality, and it is ready to insist that its weaker neighbors adhere to them.

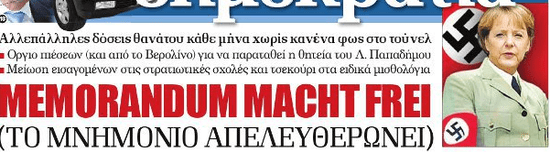

(Detail from the front page of the Greek newspaper Demokratia from Twitter user @fgoria.)