Umberto Eco, who curated the show "The Infinity of Lists," offers an answer:

The list is the origin of culture. It’s part of the history of art and literature. What does culture want? To make infinity comprehensible. It also wants to create order—not always, but often. And how, as a human being, does one face infinity? How does one attempt to grasp the incomprehensible? Through lists, through catalogs, through collections in museums and through encyclopedias and dictionaries.

Jillian Steinhauer delves deeper:

According to Robert Belknap in his book The List: The Uses and Pleasures of Cataloguing—a study of literary lists, particularly in the work of four American Renaissance authors—lists of sequential signs appeared as early as 3,200 B.C.E. Used as a means of accounting and record keeping, they signified an early form of communication that would evolve into written language. If this is true, then Eco is right: the list is the origin of culture. In his own book, Eco goes back to ancient history to find examples of literary lists. Homer, in The Iliad, spends 350 verses naming generals and ships in the Greek army.

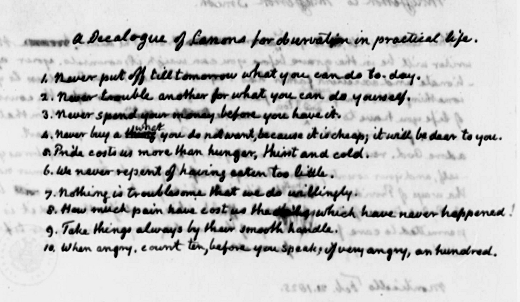

(Image: "A Decalogue of Canons for observation in practical life" by Thomas Jefferson, beginning with "Never put off till tomorrow what you can do to-day." Via Lists Of Note.)