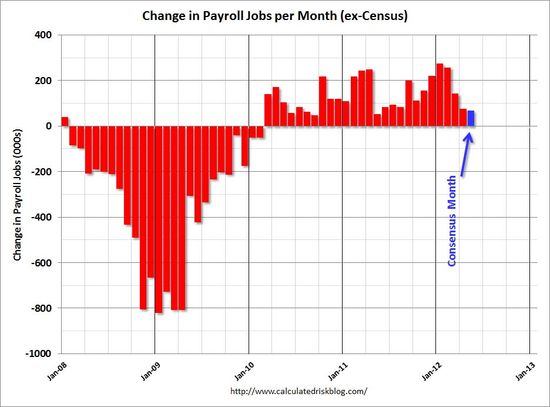

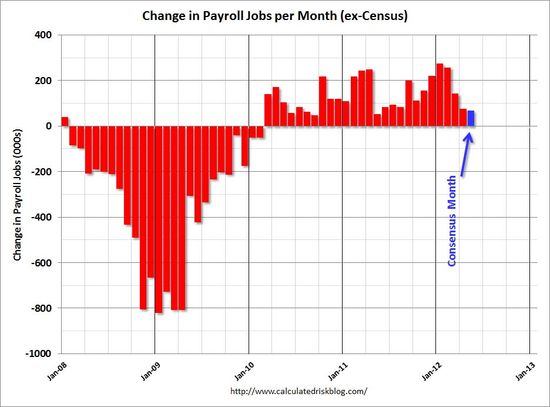

Leonhardt notices a pattern:

Some combination of problems – Europe’s new troubles, the rise in gas prices from several months ago, the continued cuts in government employment, the continued hangover from the financial crisis – has clearly slowed the economy. You can look at either survey that the Labor Department does, of businesses or households, and you can look at any time period. The message is the same. For the third straight year, the economy has fallen into a spring slump.

Daniel Gross sees no silver lining:

Every month, when it reports the figures, BLS goes back and revises the figures it had reported for the prior two months. For much of this recovery, the trend has been for BLS to discover jobs that hadn't been originally reported and revise the prior months' totals higher. But not this month. In May, BLS revised the gains for the two previous months lower. March's figure, originally reported as a 120,000 gain, had been revised upward to 154,000 in April, was revised back down to 143,000. The April figure, originally reported as a gain of 115,000, was revised to a gain of only 77,000.

Brad Plumer digs into the report's details:

Much of the job carnage seems to be driven by the construction sector, which lost 28,000 jobs last month. As Jed Kolko of the housing research firm Trulia notes, construction jobs now make up just 4.1 percent of all employment — the lowest level since 1946. And the United States hasn’t added any new construction jobs, on net, since the beginning of last year. There’s still a massive hangover from the housing bubble.

Mark Perry searches for economic bright spots. Among them:

The jobless rate for college graduates fell to 3.9% in May, the lowest unemployment rate for that group since December 2008, almost three and-a-half years ago.

Jamelle Bouie considers political consequences:

Obviously, this has political implications, and none of them are good for Barack Obama. In the short term, this gives the Romney team an excellent talking point and bolsters their depressingly effective message of facts (the economy is sluggish) and falsehoods (Obama hasn’t created a single job). Obama can recover from this, but only if summer sees a significant improvement in the employment situation. Right now, Obama is the slight favorite in this election. If this continues to the fall, he’ll almost certainly be the underdog.

Ryan Avent agrees:

Mr Obama will no doubt protest that things would have been worse without his efforts, that additional fiscal stimulus is impossible thanks to Republican opposition, and that trouble abroad, over which he has no control, is largely to blame. On the merits, he'll be mostly right. Voters are unlikely to feel much sympathy, however. Their attention will be overwhelmingly focused on a recovery that has, for a third year running, left the country saddled with far too much unemployment and far too little job growth.

Yglesias dismisses the horserace chatter:

[I]t's important to remember that this is first and foremost a human trajedy for unemployed and underemployed people, and for employed workers who've been stripped of bargaining power due to persistent labor market weakness. If growth stays dismal and Barack Obama loses the election, he and Michelle and Jack Lew and Tim Geithner and all the rest will go on to have happy, healthy, prosperous lives. Other people's careers are much more in the balance.

Jared Bernstein blames the economic weakness on Washington:

The economic reason the job market is once again downshifting is because we as a nation failed to take out recovery insurance in the form of temporary stimulative fiscal policy against precisely the situation we now face.

Felix Salmon calls for more stimulus:

The government can borrow at 1.45%: it should do so, in vast quantities, and invest that money back into the economy itself. Take a few hundred billion dollars and use it to fix our broken infrastructure, to re-hire all those laid-off teachers and firefighters, to provide some kind of safety net for the millions of Americans who have been out of work for more than a year. Even if the real long-term return on any stimulus package was zero, the nominal long-term return would be well over 1.45%, making the investment worthwhile.

Buttonwood points out that more stimulus is politically impossible and is watching the Fed instead. Binyamin Appelbaum likewise keeps his eyes on Ben Bernanke:

Senior officials have said repeatedly in recent months that the bar for additional action is unusually high at the moment, because any additional steps to encourage growth would have to be huge to be meaningful. Many analysts also feel that the Fed is more reluctant to take action during a presidential campaign.

Chart from Calculated Risk.