A reader writes:

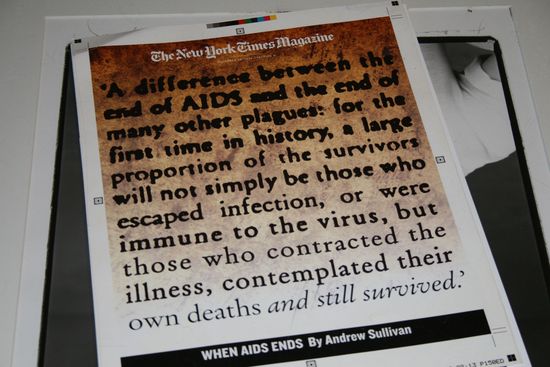

I just read your post about surviving the plague and thought of your 1996 NY Times magazine cover for “When Plagues End” that starts in a fuzzy font and becomes clear and talks about a plague where survivors had contemplated their own mortality but survived. (paraphrased). I wish you would post it on your blog.

I had torn this off and framed it for my office years ago, as it really spoke to me. I had been a 3rd year med student in 1986 at Roosevelt hospital in NYC where every abnormal chest Xray was PCP, former models were distorted by KS lesions all over their faces, AIDS dementia and continuous diarrhea made others a difficult challenge for partners who loved them still. I had also been an infectious disease fellow in 1993-5 when suddenly my patients’ Tcells were magically going UP on new combinations of AZT and 3TC and to zero once we had saquinavir. I’ve trained younger docs more recently who hadn’t ever seen PCP. A miracle.

I hadn’t looked at that framed cover since a move several years ago. When I unpacked some things from storage recently I was surprised to see it had been written by you! I started being a regular Dish reader about 4-5 years ago, long after that article was written. Anyway, just wanted to say thanks to you and the graphic artist. I loved that cover.

Chip Kidd designed it. It’s worth recalling that the piece was arguably the most controversial thing I’d ever written. The response was immediate and extremely hostile from within the gay community. I was wrong, I was irresponsible, etc etc. Alas, the piece didn’t say what many who didn’t read it assumed it said. I was fascinated by the psychology of grappling with the end of plagues – not of diseases. A plague is a widespread virus for which there is no cure and which is close to 100 percent fatal. A disease is something that can be treated. HIV went in America from being one to being the other as suddenly as in La Peste. Another reader:

We are blood brothers. I’m from NYC originally, and before my 30th birthday I had attended 19 funerals of friends who succumbed to AIDS, including my first partner. I left corporate law practice to spend most of my career managing AIDS service programs, and expected to die there. Science trumped the virus and here I am, healthy as a horse and impoverished. Except the strength, passion and friendships I developed in the AIDS community is a wealth of sorts. If there is a God, and I doubt it, he owes us an apology.

Another:

The line “1996 was a real nail-biter” hit me in the gut. My uncle died an agonizing death in January of that year after a very rapid decline in the preceding months.

When there was nothing else that could be done in the hospital, my grandmother brought him home to die in his childhood bedroom. He had very strange symptoms – almost like a chemical burn from the inside out over his entire body – that may or may not have been related to the alternative treatments he pursued out of desperation. His skin was so thin and fragile it couldn’t hold an IV for the morphine drip. I was a freshman in college. I went back after the winter break and told very few people – not out of shame but because I was burning with so much anger that I feared what would come out if I opened my mouth.

And then, within a year, it was over. People just stopped dying. Former boyfriends of my uncle who had seemed to be on death’s door for longer than he had even been sick started to put on weight and make plans for the future. I saw one of them a few years ago on a visit home. He looked great. It’s hard, even so many years later, not to think about what might have happened if he’d held on just a little more or not gone to that quack or, or, or … But that’s not the way it happened.

Another:

I got to come out in those years of fear of sickness and death. I made many mistakes because of that fear, like rushing into a long-term relationship I was not ready for with a guy I was not quite compatible with, then being promiscuous enough to get Hepatitis B (probably by oral route). I joined ACT UP/Boston for a while, but got annoyed with the group. I felt like they were pushing the drug companies and FDA too fast and beyond good scientific practice. This resulted in some drugs causing harm rather than helping (like ddI and neuropathy due to too high doses).

I was struck by the second image you picked, which was clearly from the same ACT UP protest at Astra Pharmaceuticals in Weston, MA, that I first went to as a photographer for Boston’s BayWindows in 1989. I remember being astounded that the cops were all wearing latex exam gloves, even though by 1989 we knew HIV was not transmissible by touching an infected person’s skin. The protesters chanted to the cops, “Your gloves don’t match your shoes.” One of the writers on staff at the paper was dating the protester raising his arms in the picture, who subsequently died of a Hepatitis B opportunistic infection.

I’m now married to the same fellow I have been living with since 1991 (second boyfriend, hitched since 2007) and turn my cameras more often on peaceful landscapes than on protests.

Another:

I’ve been following your discussion about AIDS with interest. Some of us in the younger generation (I’m 35) were affected by it, too. My husband, who is now 30, lost his favorite uncle Ricky to AIDS in 1994, when he was only 12 years old. Ricky was charismatic and flamboyant (I’m sorry, there’s no other word) and ran an African dance school on the south side of Chicago. His sexuality was never discussed openly, though it must have been understood that he was gay – but his “lifestyle” was shrouded in shame and silence. My now-husband got his first introduction to dance through Ricky’s school, which opened up an entirely new world to him, and eventually led him out of the urban ghetto of Chicago and into a career as a professional ballet dancer. I will forever be grateful to Ricky, who I never had the chance to meet, for opening up this world of opportunity to him.

We met in 2005, when he was 23. In 2009 we were married, legally, in Massachusetts – with both of our families in attendance. Our wedding was a mixture of black and Jewish traditions, and we constructed a chuppah out of garments that had belonged to departed loved ones from each of our families, including a piece of clothing that had belonged to Ricky. As we stood under that chuppah, affirming our love and commitment to one another in front of our friends and family, I couldn’t help but think that we were fulfilling a dream that Ricky hadn’t been able to realize; that he had died – that he had been killed – by the shame and silence that we were seeking to banish; and that his family has gotten a second chance, with us, at redemption – to accept us, affirm us, love us, and not exile us to isolation and shame.

More stories from our readers at our Facebook page. The Dish thread so far is here, here and here.

(Photo by Steven Keirstead)

Outside of Twitter, a coercive blogginess, a paradoxically de rigueur relaxation, menaces a whole generation’s prose (no, yeah, ours too). You won’t sound contemporary and for real unless it sounds like you’re writing off the top of your head. Thus: "In The Jargon of Authenticity, Adorno went bonkers with rage, and took off after Heidegger and the existentialists with a buzz saw, loudly condemning the sloppy word that these dumb existentialists sloppily use to brag about how they know what is real and what isn’t." This appeared on a blog (The Awl), so its blogginess shouldn’t be held too much against it. But all contemporary publications tend toward the condition of blogs, and soon, if not yet already, it will seem pretentious, elitist, and old-fashioned to write anything, anywhere, with patience and care.

Outside of Twitter, a coercive blogginess, a paradoxically de rigueur relaxation, menaces a whole generation’s prose (no, yeah, ours too). You won’t sound contemporary and for real unless it sounds like you’re writing off the top of your head. Thus: "In The Jargon of Authenticity, Adorno went bonkers with rage, and took off after Heidegger and the existentialists with a buzz saw, loudly condemning the sloppy word that these dumb existentialists sloppily use to brag about how they know what is real and what isn’t." This appeared on a blog (The Awl), so its blogginess shouldn’t be held too much against it. But all contemporary publications tend toward the condition of blogs, and soon, if not yet already, it will seem pretentious, elitist, and old-fashioned to write anything, anywhere, with patience and care.