by Patrick Appel

A reader writes:

I don't necessarily disagree with the fact that coal will be an important part of our energy mix (especially on a worldwide scale) for a long time to come, but I really don't like the tone of these articles. "Give up hope, all ye American coal foes. Your efforts are for naught. Why even bother?" I wrote about this in response to Fallows' article a few years ago. I like Fallows, his writing is usually high quality and thought-provoking, but those pieces on the necessity of clean coal were not up to his usual standards. He cherry-picked from the available data (using a quote from Robert Bryce) to make his point:

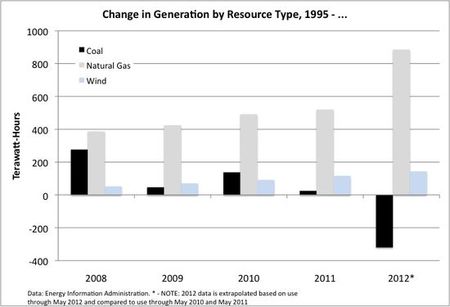

The journalist Robert Bryce has drawn on U.S. government figures to show that between 1995 and 2008, ‘the absolute increase in total electricity produced by coal was about 5.8 times as great as the increase from wind and 823 times as great as the increase from solar.’ – and this during the dawn of the green-energy era in America.

His data wasn't wrong; between 1995 and 2008 that was indeed the case. But he wrote his article in 2010 … and left out the most recent data. Had he included the most current EIA data to that point, the story would be a different one: rather than the absolute increase in coal generation being almost six times as great as the increase in wind, the increase in wind would be about 1.2x that of coal. If you update to include the most current data available from the EIA, it seems pretty clear that the current trend is toward natural gas and wind, not coal:

Yes, it's true that this is the situation in America, and Bryce's point is that America does not control (or even have much of an influence on) the international coal market. But the bigger issue facing the future of electricity generation worldwide is more general than "we need clean coal". Instead, I think the issue should always be framed as "we need clean, dispatchable baseload resources". Whether that's coal with carbon capture and sequestration, better storage technologies to smooth out intermittent generation, biomass (cellulosic ethanol maybe?), nuclear (with thought given to the disposal of the nuclear waste), or something completely different is yet to be determined. If the US leads the way in solving this problem, maybe we can make it so that other countries choose (like we are currently doing) to use less coal.

I think the most appropriate comparison for those pushing clean coals is to think back 10 years to the discussion of the next step in car technology. In the 2000s, a lot of people were touting Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles as the "internal combustion engine killer." California went so far as to develop a plan for a statewide hydrogen refueling infrastructure to encourage the switch. And yet, when was the last time you heard about FCVs? The focus has shifted back to electric vehicles, because the problems with batteries proved easier to overcome than the problems with storing hydrogen. The situation for cleaner baseload electricity is similar: all of the options have significant barriers to overcome before they can make a difference, and it's not clear that those problems are less severe for CCS than they are for Solar Thermal with Thermal Storage, or giant batteries that can smooth generation, or maybe even fuel cells (like those made by Bloom Energy) powered by renewably-generated hydrogen. It's just too early to say (as Fallows does) that clean coal is really that important.

I actually exchanged e-mails with Fallows at the time the clean coal article was written, asking him why he didn't mention the 11% drop in coal generation from 2008 – 2009. He said he viewed it as an anomaly rather than a long term trend, saying "we'll see." I think the chart above indicates it's more of a trend than an anomaly.