by Zoë Pollock

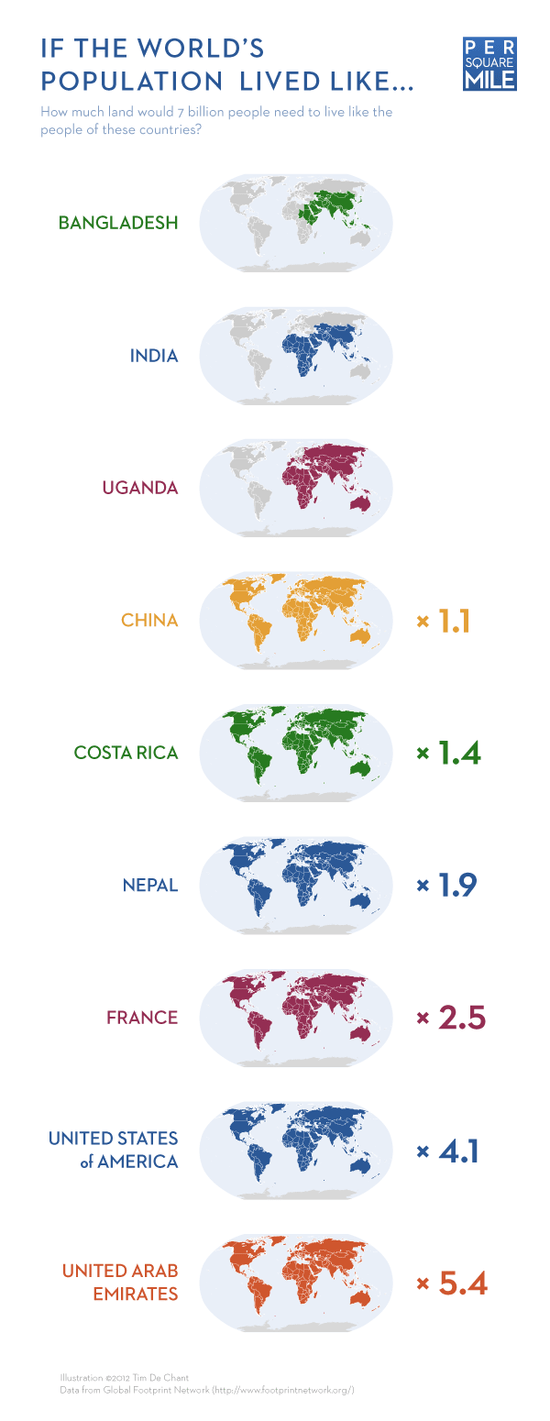

Last year, Tim De Chant published a map showing how much land the globe's 7 billion people would require if they were as densely housed as the residents of various cities. Now he's done a similar job mapping the ecological footprints of countries across the world. He compares the two projects:

Cities’ land requirements far outstrip their immediate physical footprints. They include everything from farmland to transportation networks to forests and open space that recharge fresh water sources like rivers and aquifers. And more. Just looking at a city’s geographic extents ignores its more important ecological footprint. How much land would we really need if everyone lived like New Yorkers versus Houstonians? It turns out that question is maddeningly difficult to answer. While some cities track resource use, most don’t. … But what we can do is compare different countries and how many resources their people—and their lifestyles—use. For countries, the differences are far, far greater than for cities.

The full chart is after the jump because it's a little long:

[Tocqueville’s] most interesting argument was that the mores and the habits of the people are what keep the U.S. great. As you all know, many countries have adopted a system of constitutional arrangements very similar to that which you find in the U.S. In Mexico, in the Philippines, indeed, in most of Latin America you find duplicates of the American Constitution. But despite these duplicates and despite the fact that some countries, like Argentina, are rich in natural resources, you do not find our tradition of settled government, a respect for the rights of others, and the slow emergence of freedom which leads you to give due regard to the interests of other people without abandoning your commitment to the country as a whole.

[Tocqueville’s] most interesting argument was that the mores and the habits of the people are what keep the U.S. great. As you all know, many countries have adopted a system of constitutional arrangements very similar to that which you find in the U.S. In Mexico, in the Philippines, indeed, in most of Latin America you find duplicates of the American Constitution. But despite these duplicates and despite the fact that some countries, like Argentina, are rich in natural resources, you do not find our tradition of settled government, a respect for the rights of others, and the slow emergence of freedom which leads you to give due regard to the interests of other people without abandoning your commitment to the country as a whole.