Greg Ip summarizes a disappointing report:

Otherwise ordinary news feels like bad news in the face of high expectations. So it is with America's economy. The August employment report was subdued, but not disastrous. Non-farm jobs rose 96,000 from July, or 0.1%, and the unemployment rate dropped to 8.1%, from 8.3%. Both figures show a job market on the same pace it has been since the winter: expanding just about quickly enough to keep the unemployment rate from rising, but no faster. The economy remains balanced between slowdown and recovery.

Dylan Matthews flags a harrowing statistic:

Labor force participation fell from 63.7 percent of the non-imprisoned population over 16 to 63.5 percent. That’s not just the lowest level since the recession hit, it’s the lowest level since September 1981, and the lowest level for men since the BLS started keeping track in 1948.

Derek Thompson takes stock:

The economy is now officially behind schedule compared to 2011. Average monthly job gains last year? 153,000. This year? 139,000. Over the past three months, the average has slipped to 94,000. That is probably either at, or just below, the rate of population growth.

Yglesias considers the politics of the report:

I think Obama's fortunes might be bolstered by the fact that the household survey showed a smallish decline in the unemployment rate. The unemployment rate is I think a better-known indicator to the average person, and a decline is better than a non-decline. The reality, however, is that this was basically driven by people dropping out of the labor force. Not all of that is a bad thing per se—it's fine for people to retire early or whatever—but it's hard to see it as "good news" for the economy on any level. It strikes me as very odd that Obama, who knew this report was coming, made no reference to any plans to fight unemployment in his speech.

Ezra Klein adds:

The administration is not without answers. The American Jobs Act is a serious, real policy proposal that would boost the labor market right now. Private forecasters estimate that it would add around 2 million new jobs over the next two years. In stark contrast to the policies outlined last night, which would be as appropriate in 2005 or 1995 as they are today, the American Jobs Act is actually designed for jobs crisis we’re in, and wouldn’t make much sense in more normal times. And yet, insofar as the president mentioned it, it was only a glancing, opaque reference.

Christopher Matthews wonders if the Fed will act:

[W]ith fiscal policy hamstrung by a fierce political election, the central bank is the only part of the government that has the capacity to act. The political effects of the job report are unknown at this point, as there will be two more jobs reports between now and ballot day (including one just five days before the November election), but we will find out what the Federal Reserve thinks of all this when it next meets on September 12.

Peter Boockvar thinks markets are asking the same question:

Bottom line, lame job growth continues, averaging just 139k per month year to date but all the markets are focused on is how central bankers will deal with the slowdown with more policy action.

And Kevin Roose puts the Fed debate in context:

[W]hen you're reduced to cheering up a dismal jobs report by arguing "well, at least now the Fed is more likely to take an emergency measure to stimulate the economy!", you've already conceded that the folks on Main Street are right to feel nothing but pessimism. Because, remember, that's what QE3 is: an emergency measure, meant for use in a bona fide crisis. The fact that some of us now expect policymakers to use these kinds of tools on a more or less regular basis is a reflection of how much we've acclimated to our situation. Emergency measures have become, to use this magazine's least-favorite phrase, the new normal.

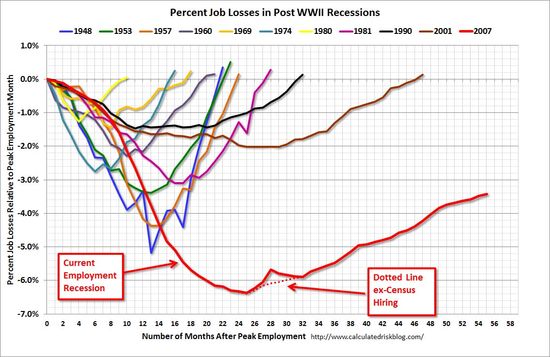

Chart from Calculated Risk.