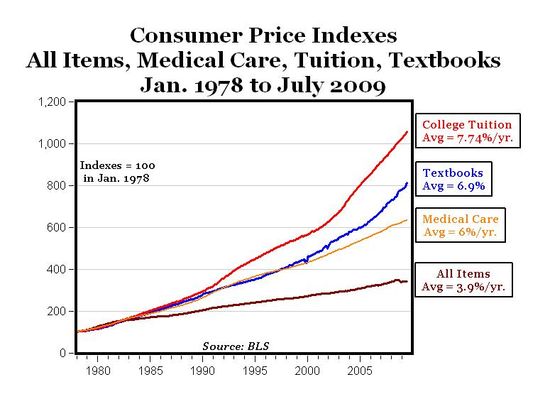

With student debt skyrocketing and college costs continuing to increase well over the rate of inflation, McArdle questions college's return-on-investment, especially if students are seeking the experience or the degree more than the actual knowledge:

[W]hile the value of an education can be very high, the value of a credential is strictly limited. If students are gaining real, valuable skills in school, then putting more students into college will increase the productive capacity of firms and the economy—a net gain for everyone. Credentials, meanwhile, are a zero-sum game. They don’t create value; they just reallocate it, in the same way that rising home values serve to ration slots in good public schools. If employers have mostly been using college degrees to weed out the inept and the unmotivated, then getting more people into college simply means more competition for a limited number of well-paying jobs. And in the current environment, that means a lot of people borrowing money for jobs they won’t get.

But we keep buying because after two decades prudent Americans who want a little financial security don’t have much left. Lifetime employment, and the pensions that went with it, have now joined outhouses, hitching posts, and rotary-dial telephones as something that wide-eyed children may hear about from their grandparents but will never see for themselves. The fabulous stock-market returns that promised an alternative form of protection proved even less durable. At least we have the house, weary Americans told each other, and the luckier ones still do, as they are reminded every time their shaking hand writes out another check for a mortgage that’s worth more than the home that secures it. What’s left is … investing in ourselves. Even if we’re not such a good bet.

Along the same lines, M.C.K. at Free Exchange calls policies to up college enrollment fairly ineffectual:

Chang [Ha-Joon] has noted that Switzerland—one of the richest countries in the world and the nation with the third-highest ratio of Nobel scientists per person—has a lower rate of college enrollment than every other rich nation, as well as other beacons of prosperity like Argentina, Lithuania, and Greece. In fact, once a country has crossed some very low threshold, there is no relationship between the number of graduates and national wealth. The explanation is simple: a typical college education does not linearly increase labor productivity.

(Chart from Tyler Cowen)