Greg Ip puts QE3 in perspective:

Between the ECB’s action last week and the Fed’s today, the world’s two most important central banks are bringing unprecedented resolve to bear on economic growth. The world may one day look back and conclude the first half of September was either a turning point for the global economy, or the final nail in the coffin of the doctrine of central bank omnipotence.

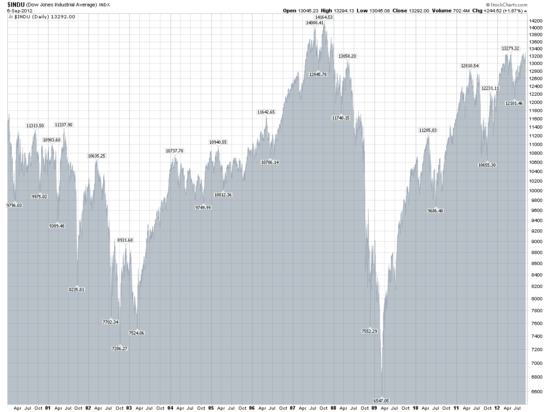

Stocks, meanwhile have doubled in value since Obama took office (see graph above). In April 2009, it was at 6,500. Today, it is at 13,600. Sarah Binder explains why Bernanke waited so long:

Judging from Bernanke’s comments … he waited far longer than a more autocratic chair might have deemed necessary. Indeed, he noted that the consensus across the FOMC was so broad, that “even as personnel changes going forward, this will be seen as the appropriate approach and we will have created a reserve of credibility we can use in subsequent episodes.” That line was probably the most important statement of the day, as it provided a glimpse of Bernanke’s strategy for addressing the intense and continuing criticism of the Fed: Build as deep and broad a consensus for aggressive Fed action, so that the Fed’s audiences will come to concur that the course of action is “appropriate”—even after Bernanke’s term as chair ends. Such confidence might be premature, but it suggests the hard challenge Bernanke has faced in leading the Fed in a polarized political environment marked by pockets of deep distrust of the Fed.

Dave Weigel rounds up the typically vague Republican outrage about QE3. Ron Paul, meanwhile, describes some more vivid concerns for the American people:

I don’t think he should raise rates. He should just get out of rigging rates. The system is so biased. It helps the bankers who get free money and then they buy government debt. What about the people who are frightened, they do not like the stock market and they are frugal and want to take care of themselves? What do they get—1% on a CD? That is unfair.

Brad Plumer touched on some of these issues last month:

If a central bank’s easing efforts bolster the broader economy, then the trade-off might be worth it. “The fact that the rich have benefited most from QE does not mean that others haven’t benefited,” writes economist Chris Dillow. ”People without financial assets have gained, to the (small) extent that QE has increased job security and raised inflation, thus eroding the value of debt.”

Indeed, a recent NBER paper (pdf) argues that overly tight monetary policy that keeps unemployment high is far more likely to exacerbate inequality than anything else. On this view, improving the job market is the best thing the Fed can do on inequality, regardless of the near-term effects.

Bear in mind that the Fed is ultimately just the backstop, he notes:

[I]t’s worth noting that more fiscal stimulus from Congress could be a way of boosting the economy without pumping up the assets of the wealthiest. Indeed, at certain points Ben Bernanke has pleaded with Congress to do more to support the economy. But Congress isn’t doing much, which is why there’s so much attention these days on QE3.

Which is why Obama's re-election is so crucial for our economic near and distant future.