Robert Boyers ponders how the genre's definition has evolved over the years, from something explicit to, more broadly, "the intersection of public and private life":

At a public interview I conducted with Nadine Gordimer thirty years ago, she bristled at my use of the epithet “political novel” to describe her masterwork, Burger’s Daughter. It was not, Gordimer argued, written to promote an agenda. It did not subscribe to a particular idea or ideology. To call it a political novel was to suggest that it had–as Henry James once put it–“designs” upon us, that its author wished to banish incorrect opinions and to install in their place clearly more beneficial views of politics and society. At their best, Gordimer contended, novels were not useful. If I admired her novel as much as I said I did, I would do better to regard it as a free work of the imagination, an inquiry with no purpose that involved providing answers to the difficult questions it posed.

I had no intention of reducing Gordimer’s book to a species of blunt propaganda, and I thought of the epithet simply as a shorthand for “a novel invested in politics as a way of thinking about the fate of society at a particular place and time.”

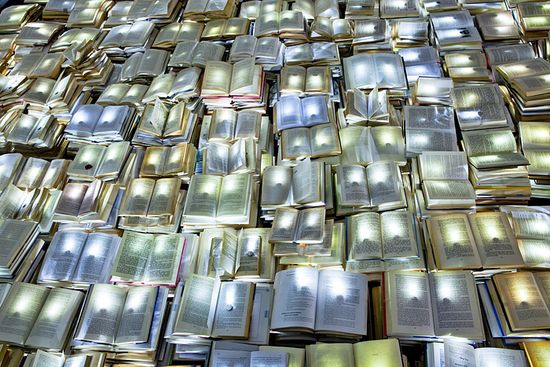

(Image from the installation Literature vs Traffic by Luzinterruptus via Wooster Collective)