Release your inner beast:

Month: January 2013

Diagnosis Down Below

In the new book Shakespeare’s Tremor and Orwell’s Cough, Dr. John J. Ross recounts the medical lives of our favorite writers. On the Bard’s possible syphillis:

The only medical fact known about Shakespeare with certainty is that his final signatures show a marked tremor. … According to contemporary gossip, Shakespeare was not only notoriously promiscuous, but was also part of a love triangle in which all three parties contracted venereal disease. The standard Elizabethan treatment for syphilis was mercury; as the saying goes, “a night with Venus, a lifetime with Mercury.” Mercury’s more alarming adverse effects include drooling, gum disease, personality changes, and tremor. (In the eighteenth century, mercury was used in the manufacture of felt hats, leading to the expressions “hatter’s shakes” and “mad as a hatter”).

Meanwhile, Maggie Koerth-Baker discovers that Anne of Green Gables had herpes. But then again, you probably do too:

Unlike herpes simplex type 2 — the virus you probably think of when you think “herpes” — HSV-1 isn’t necessarily a sexually transmitted disease. Most people are infected when they’re still little kids. And they’re infected by really common behaviors that nobody wants to stop anytime soon — namely, the practice of adults kissing little kids because they’re just so darn kissable. (There are several scenes in Anne of Ingleside where Anne probably passes HSV-1 on to her own offspring.)

But she warns that oral herpes isn’t confined to the mouth:

Truth is, HSV-1 can pass from one host to another via any mucus membrane, and that includes the ones on your genitals. If somebody with oral herpes goes down on you, there’s a possibility that they could give you oral herpes in a place that is most definitely not your mouth. And cases of this happening are one the rise.

High School Biology

In a long essay on the formative impact high school has on us, Jennifer Senior unpacks the science behind these crucial years:

[T]he prefrontal cortex has not yet finished developing in adolescents. It’s still adding myelin, the fatty white substance that speeds up and improves neural connections, and until those connections are consolidated—which most researchers now believe is sometime in our mid-twenties—the more primitive, emotional parts of the brain (known collectively as the limbic system) have a more significant influence. This explains why adolescents are such notoriously poor models of self-regulation, and why they’re so much more dramatic—“more Kirk than Spock,” in the words of B. J. Casey, a neuroscientist at Weill Medical College of Cornell University. In adolescence, the brain is also buzzing with more dopamine activity than at any other time in the human life cycle, so everything an adolescent does—everything an adolescent feels—is just a little bit more intense. “And you never get back to that intensity,” says Casey. (The British psychoanalyst Adam Phillips has a slightly different way of saying this: “Puberty,” he writes, “is everyone’s first experience of a sentient madness.”)

Liberal Reagan Watch

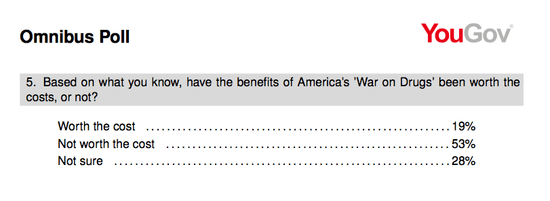

Part of it is about the culture, regardless of the actual actions of a president (which, in Obama’s case, have been piddling and pathetic when they haven’t been appalling):

So we have a huge amount of money to cut and save. Why not start with re-classifying cannabis according to science not bigotry, and deploying police resources on actual crimes worthy of the name?

The King’s Apostrophe

The most entertaining grammar lesson you’ll watch this weekend:

The Death Of The Bookstore

J.L. Wall fears that it will limit exposure to the classics:

Without the physical store, without the displays, the tables, the deals, the promise of no additional critical essays, what will guide a reader (no matter their age) to Herodotus, Thoreau, or Willa Cather outside a class syllabus? There’s great promise in the possibility of out-of-copyright works becoming more accessible to more readers than ever before—but there’s also danger in the thought that there will be nothing to guide a reader toward them by chance encounter, that they might come to smell even more of musty classroom learning than before.

Wall’s fears would not be assuaged at the recent Digital Book World conference:

“Look at a book as a bag of words,” suggested Matt MacInnis, another panelist, who had been working on education projects at Apple before forming an interactive-book company called Inkling. “Bag of words,” he pointed out, is a computer-science term: a model by which a machine represents natural language. “Computers are terrible at natural language,” he said. “Humans are shitty at multiplication and division.” For a reader searching the Internet for information, he explained, “the word rank is going to be terrible for a bag of words of book length.” But a book that is broken up into component parts would show up higher in an online search result, because each discrete section coheres around a single idea, which can be tagged, indexed, and referenced by other sites. This is known in the business as “link juice.”

The Art Of The Epic Fail

In an excerpt from a new Millions ebook, Epic Fail: Bad Art, Viral Fame, and the History of the Worst Thing Ever, Mark O’Connell explores “the paradoxically humanistic and cruel constitution of the Epic Fail,” using the Jesus Fresco as a primary example:

[The Epic Fail] is predicated not just on the appreciation of the failed artwork but also on the aesthetic fetish for a particular misalignment of confidence and competence. We insist, in our judgments, on a sort of cultural habeas corpus. We don’t just want to look at the horribly disfigured Jesus fresco or listen to the horribly misfired effort at a pop song; we want to look at the person who thought they were talented enough to pull these things off in the first place. And I think part of our perverse attraction to these people and to the bad art they make is a particular sort of authenticity.

Vigilant self-consciousness is both a primary component and a primary product of our online culture; an entire generation of Westerners (i.e., mine) has become preoccupied with the curation of permanent exhibitions of the self. We hate ourselves for the inauthenticity of these exhibitions, even if we wouldn’t have it any other way. And so the Epic Fail is, among other things, a paradoxical ritual whereby a pure strain of un-self-consciousness is globally venerated and ridiculed.

(Image: A painting of the Ecce Homo x Ikea Monkey, aka “Ikeas Homonkulus” via Marina Galperina)

Silent Reading Time

First, a cool visualization showing how much languages involve silent letters:

Meanwhile, scientists have shown that even when we are reading silently to ourselves, our brains are still hearing:

What’s particularly new about this study is that it not only shows that silent reading causes high-frequency electrical activity in auditory areas, but it shows that these areas as specific to voices speaking a language. This activity was only present when the person was paying attention to the task. The authors believe that these results back up the hypothesis that we all produce an “inner voice” when reading silently. And it is enhanced by attention, suggesting that it’s probably not an automatic process, but something that occurs when we attentively process what we are reading. And the next time you read silently, remember that it’s not quite to silent to your brain.

Wilder’s Skeletons

Reviews of Penelope Niven’s new biography of Thornton Wilder have highlighted how little we know of the author’s love life, if he had one at all. Natalie Shapero believes Wilder’s play, Our Town, might reveal something about this “lonesomeness or closeted-ness or asexuality or whatever it was”:

From Emily’s place in the graveyard (an encampment of folding chairs set off to the side of the town), she decides, over the cautionings of the other dead people, to return to the world of the living for one day. She scarcely makes it through breakfast, though, before being unable to press on. It’s too hard for people to “realize life while they live it–every, every minute.” Before she returns to the little dead village of chairs, Emily says goodbye to an enumerated list of what she loves about life. In this monologue, she barely mentions other people. For the most part, she names sensory experiences of the world that we really have alone, interactions between our bodies and the physics around us. She says goodbye to the ticking of clocks, to hot baths, to sunflowers. She says goodbye to sleeping! As distinct from death. As part of what makes us alive. …

It is not someone summing up her life by locating her place in a grand social fabric. It is simply an affirmation of the experience of being a creature, to say that each small sensory moment has a deep meaning unto itself, that our wholly interior responses to the built world are what makes life worth it, even in this fantasy of return.

The View From Your Window Contest

You have until noon on Tuesday to guess it. City and/or state first, then country. Please put the location in the subject heading, along with any description within the email. If no one guesses the exact location, proximity counts. Be sure to email entries to VFYWcontest@gmail.com. Winner gets a free The View From Your Window book. Have at it.