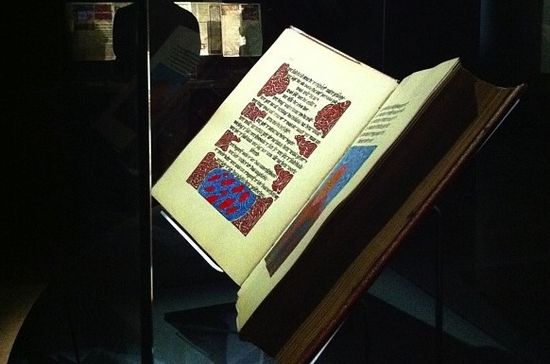

In a long, highly critical review of Carl Jung's posthumously published Red Book, which he describes as "a secret visionary tome, written in the master’s own hand, containing the mystic key to all his thought," David Bentley Hart drop these lines about the spiritual condition of our age:

Every historical period has its own presiding powers and principalities on high. Ours, for what it is worth, seem to want to make us happy, even if only in an inert sort of way. Every age passes away in time, moreover, and late modernity is only an epoch. This being so, one should never doubt the uncanny force of what Freud called die Wiederkehr des Verdrängten—“the return of the repressed.” Dominant ideologies wither away, metaphysical myths exhaust their power to hold sway over cultural imaginations, material and spiritual conditions change inexorably and irreversibly. The human longing for God, however, persists from age to age. A particular cultural dispensation may succeed for a time in lulling the soul into a forgetful sleep, but the soul will still continue to hear that timeless call that comes at once from within and from beyond all things, even if for now it seems like only a voice heard in a dream. And, sooner or later, the sleeper will awaken.

(Photo of Jung's Red Book by Flickr user olivierthereaux)