Carrie Frye traces the influence that Lord Byron had on the first modern vampire story, written by his personal physician John Polidori:

“The Vampyre” was first published, in 1819, in New Monthly Magazine as a story by Byron. It created an international stir. A play and then an opera were based on it, events that seem unlikely to have occurred if the story had gone into the world as the work of a London physician. It’s widely assumed that Polidori passed the story off as Byron’s in an intentional imposture, but the evidence there is murky. Just as possible is that, the manuscript having passed through several hands after Polidori wrote it, the details of its connection to Byron grew confused on the way to publication. (Byron, breezily waving it off: “… I scarcely think anyone who knows me would believe the thing in the Magazine to be mine, even if they saw it in my own hieroglyphics.” He might just as well have added: “He can’t jump either.”)

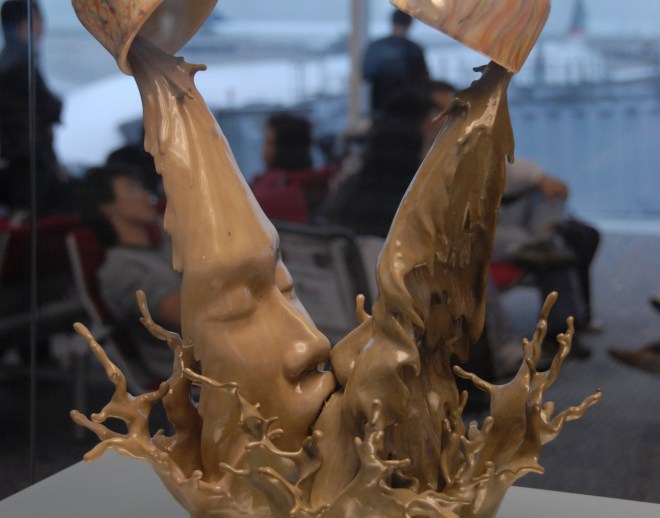

(Image: “Lord Byron on his Death-bed” by Joseph Denis Odevaere, via Wikimedia Commons)