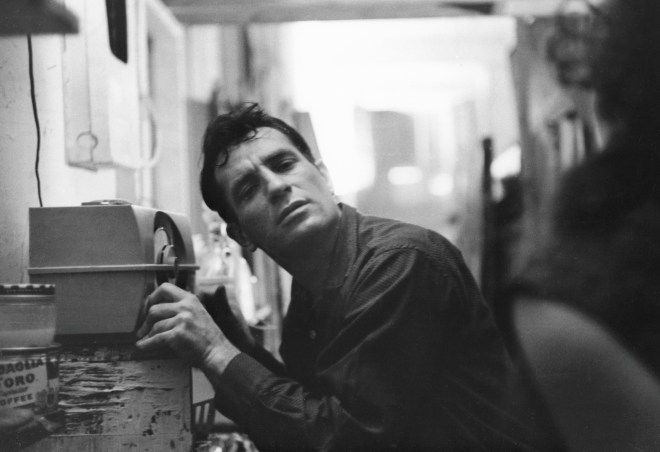

Bert Archer asks photojournalist Don McCullin, who has a retrospective at the National Gallery in Ottawa until April, about the value of his images:

Isn’t it better, I ask, realizing I’m sounding like Spock even as I say it, to benefit the hundred thousand who get a better idea of war, and are perhaps moved to oppose in, both specifically and in general, even if it does discomfit the friends and family of this or that dead soldier? Shouldn’t we continue showing these pictures for the many, rather than getting too caught up with the few?

“I think we shouldn’t,” he says. “I think we should deny the hundred thousand. In the end, I’ve done it, and I’ve realized it hasn’t proved its worth. Who have we convinced to stop the wars?”

But the images, I insist, now certainly overstepping the bounds of politesse by any definition, the images are the only thing most of us have to bring the story of war home. I tell him I only understood, only felt, what was happening in Rwanda when I saw an image of a river dammed with bodies.

McCullin hasn’t smiled often during the two conversations I’ve had with him over the past year, and he’s not smiling now. “Weren’t the images of Belsen and Dachau enough for you?”

(Photo: US marine throwing grenade, Tet Offensive, Hué, South Vietnam, February 1968 by Don McCullin / Contact Press Images. Courtesy of the National Gallery.)