Lofall, Washington, 5 pm

Month: May 2013

Life Maxims We Underline

Noreen Malone observes that the sentences Kindle-users most frequently highlight offer “a glimpse into our collective, most interior, and most embarrassing preoccupations”:

The most-noted line on all of Amazon is from the Hunger Games: Catching Fire, and it reads like something from the prologue to a self-help book: “Because sometimes things happen to people and they’re not equipped to deal with them.” The Eeyore-ish affirmation is echoed by No. 4 on the list, another [Suzanne] Collins special. “It takes ten times as long to put yourself back together as it does to fall apart.” In terms of existential despair, however, those are topped by No. 12 on the list, also from the trilogy. “We’re fickle, stupid beings with poor memories and a great gift for self-destruction.”

The bleakness of the worldview suggested by those passages is striking. It’s no surprise then, to find self-help passages appearing alongside them: They help us cope with our inherently flawed human selves. Stephen Covey’s The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People appears several times—“It’s not what happens to us, but our response to what happens to us that hurts us”—as does Dale Carnegie’s How To Win Friends and Influence People. Quotes about the healing power of God also make a strong showing, as do musings on the nature of marriage, and work, and leadership, and white carbohydrates.

Earlier Dish on the most underlined passages here.

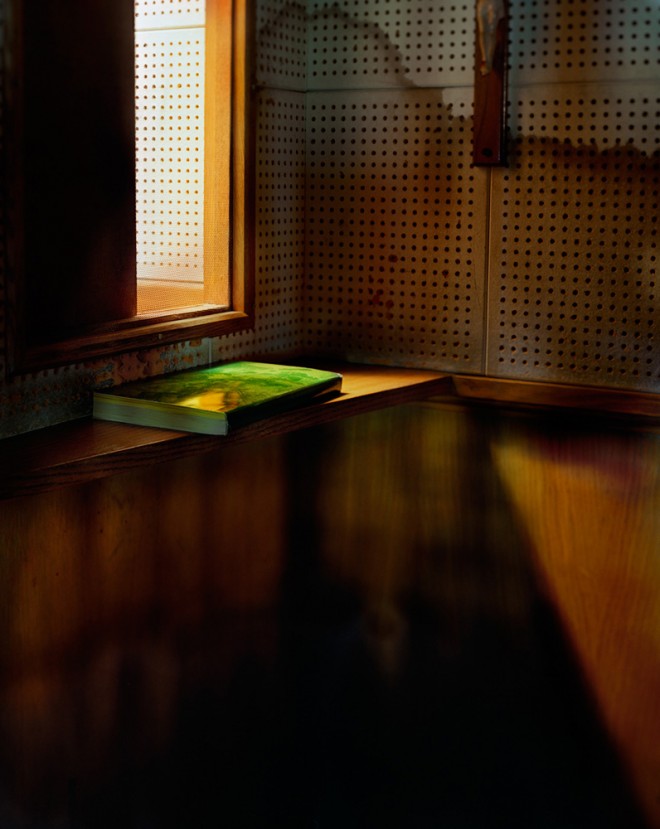

Capturing Confessionals

For her series Reconciliation, Billie Mandle photographs American confessional boxes:

These photographs were made in confessionals, the small rooms found in Catholic churches where people confess their sins. Almost all religions have theologies of repentance; the confessional is unusual because it acts as a physical manifestation of an abstract idea. …

I was raised Catholic and so the traditions of these rooms are familiar to me. Photographing the confessional has become a type of ritual: I use a large format camera and available light, lifting the curtain of the confessional and looking into the darkness, just as I lift the dark cloth of the camera. The confessionals contain contradiction: darkness and light, corporeality and transcendence. They are rooms where people confess their sins and ask for grace surrounded by the traces of past confessions. In making these images I approach the confessionals as metaphorical spaces — rooms that suggest the paradoxes of faith and forgiveness.

(Photo: Saint Christopher by Billie Mandle, from Reconciliation)

(Hat tip: Pete Brook)

Home Is Where The Homeowners Aren’t

Alan Jacobs meditates on the vagaries of our attachments to where we live:

What we always want in a home is refuge, haven, security. In Juvenal’s image, people come to the city for protection: they sleep well with neighbors close by and the gates of the city walls firmly locked and guarded. But when they find that “there is more harmony among snakes” than among people, they seek to escape: the countryside suddenly appears not as a place of threat from “nature red in tooth and claw” but as place free from the most dangerous kind of serpent. “This was my prayer,” Juvenal’s fellow Roman Horace, that gentler satirist, writes about his Sabine Farm: he always wanted to be there, or so he tells us. Maybe in fact it wasn’t so simple; maybe Machiavelli is more honest, in his portrayal of a life that in a single day finds immense frustration among disputatious rubes and peaceful colloquy with the great sages of the past.

It’s easy to see, then, why those who can afford it have both: the Manhattan apartment and the beach house in the Hamptons; the London townhouse for one season and the country house for another. English novels are filled with people who can’t wait to escape the boredom of country life for the excitement of a social season in London, and then, a little later, are equally desperate to escape and noise and bustle of the city in order to smell fresh air and hear the birds singing.

The lesson he draws:

This oscillation is perhaps more significant than it appears. Over the years that we have lived in northern Illinois, my wife Teri and I have eagerly anticipated visits with our families in our native Alabama. “It’ll be so nice to get home,” we say. But then as our return to Illinois draws closer we say, “This has been nice, but it’ll be good to get back home.” It took us several years before we realized that we were always describing the place we weren’t as “home.” This may say something about how humans think about place, what we expect from our places — and especially from the city. We ask much of it; perhaps too much.

Quote For The Day

“God would have us know that we must live as men who manage our lives without him. The God who is with us is the God who forsakes us. The God who lets us live in the world without the working hypothesis of God is the God before whom we stand continually. Before God and with God we live without God. God lets himself be pushed out of the world on to the cross. He is weak and powerless in the world, and that is precisely the way, the only way, in which he is with us and helps us. Matthew 8:17 makes it quite clear that Christ helps us, not by virtue of his omnipotence, but by virtue of his weakness and suffering.

Here is the decisive difference between Christianity and all religions. Man’s religiosity makes him look in his distress to the power of God in the world: God is the deus ex machina. The Bible directs man to God’s powerlessness and suffering; only the suffering God can help.” – Dietrich Bonhoeffer, in a letter to Eberhard Bethge, July 16, 1944, from his Letters & Papers from Prison.

Recent Dish on Bonhoeffer here.

(Photo: Homeowner Russell Shearer displays a tiny wooden cross that he recovered from the rubble of his destroyed home on May 24, 2013 in Moore, Oklahoma. By Tom Pennington/Getty Images)

Fiction Isn’t Friendship

In an interview with Claire Messud about her new novel, The Woman Upstairs, Publisher’s Weekly posed this question about the book’s main character: “I wouldn’t want to be friends with Nora, would you? Her outlook is almost unbearably grim.” In response, Messud unloaded:

For heaven’s sake, what kind of question is that? Would you want to be friends with Humbert Humbert? Would you want to be friends with Mickey Sabbath? Saleem Sinai? Hamlet? Krapp? Oedipus? Oscar Wao? Antigone? Raskolnikov? Any of the characters in The Corrections? Any of the characters in Infinite Jest? Any of the characters in anything Pynchon has ever written? Or Martin Amis? Or Orhan Pamuk? Or Alice Munro, for that matter? If you’re reading to find friends, you’re in deep trouble. We read to find life, in all its possibilities. The relevant question isn’t “is this a potential friend for me?” but “is this character alive?”

The editors of The New Yorker pointed to this as an example of “a critical double standard—that tormented, foul-mouthed, or perverse male characters are celebrated, while their female counterparts are primly dismissed as unlikeable,” and convened a roundtable on the issue of fictional characters’ “likeability.” From Margaret Atwood’s contribution:

Intelligent readers do not confuse the quality of a book with the moral rectitude of the characters. For those who want goodigoodiness, there are some Victorian good-girl religious novels that would suit them fine.

Also, what is “likeable”? We love to watch bad people do awful things in fictions, though we would not like it if they did those things to us in real life. The energy that drives any fictional plot comes from the darker forces, whether they be external (opponents of the heroine or hero) or internal (components of their selves).

Do women writers get asked this more than male ones? Bet your buttons they do. The snaps and snails and puppy-dog’s tails are great for boys. The sugar and spice is still expected for girls.

And here’s Jonathan Franzen’s response:

I hate the concept of likeability—it gave us two terms of George Bush, whom a plurality of voters wanted to have a beer with, and Facebook. You’d unfriend a lot of people if you knew them as intimately and unsparingly as a good novel would. But not the ones you actually love.

Mental Health Break

The first episode of a promising new series:

The Awe We All Share

The New York Review of Books recently ran an excerpt from the late philosopher Ronald Dworkin’s forthcoming book, Religion without God, which includes this passage:

The familiar stark divide between people of religion and without religion is too crude. Many millions of people who count themselves atheists have convictions and experiences very like and just as profound as those that believers count as religious…They find the Grand Canyon not just arresting but breathtakingly and eerily wonderful. They are not simply interested in the latest discoveries about the vast universe but enthralled by them. These are not, for them, just a matter of immediate sensuous and otherwise inexplicable response. They express a conviction that the force and wonder they sense are real, just as real as planets or pain, that moral truth and natural wonder do not simply evoke awe but call for it.

Adam Frank thinks Dworkin helpfully pointed toward the common ground the religious and non-religious share, and believes now is the time for people of goodwill to “get creative” in cultivating these similarities:

How does a culture saturated with the fruits (and poisons) of science understand the ancient human longing that is sometimes called religious, sometimes spiritual or sometimes sacred? The route of absolute rejection (taken famously by ) makes for a clean ideology. But it comes at a cost: ignoring the reality of human experience. This is why Dworkin is keen to show that — even for people who call themselves atheist — there remains a sense or a value to the world which bears so much in common with attitudes we call religious or spiritual.

A Poem For Sunday

“All That Time” by May Swenson:

I saw two trees embracing.

One leaned on the other

as if to throw her down.

But she was the upright one.

Since their twin youth, maybe she

had been pulling him toward her

all that time,and finally almost uprooted him.

He was the thin, dry, insecure one,

The most wind-warped, you could see.

And where their tops tangled

it looked like he was crying

on her shoulder.

On the other hand, maybe hehad been trying to weaken her,

break her, or at least

make her bend

over backwards for him

just a little bit.

And all that time

she was standing up to himthe best she could.

She was the most stubborn,

the straightest one, that’s a fact.

But he had been willing

to change himself—

even if it was for the worse—

all that time.At the top they looked like one

tree, where they were embracing.

It was plain they’d be

always together.

Too late now to part.

When the wind blew, you could hear

them rubbing on each other.

(From May Swenson: Collected Poems, Langdon Hammer, editor (The Library of America, 2013) © The Literary Estate of May Swenson. Photo by Flickr user Craig Sunter)

Stepping In Contemplative Bullshit

In an excerpt from his new book, Intuition Pumps And Other Tools for Thinking, Daniel Dennett offers guidelines for sound thinking, which includes a wariness of what he calls “deepities”:

A deepity (a term coined by the daughter of my late friend, computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum) is a proposition that seems both important and true – and profound – but that achieves this effect by being ambiguous. On one reading, it is manifestly false, but it would be earth-shaking if it were true; on the other reading, it is true but trivial. The unwary listener picks up the glimmer of truth from the second reading, and the devastating importance from the first reading, and thinks, Wow! That’s a deepity.

An example:

Love is just a word.

Oh wow! Cosmic. Mind-blowing, right? Wrong. On one reading, it is manifestly false. I’m not sure what love is – maybe an emotion or emotional attachment, maybe an interpersonal relationship, maybe the highest state a human mind can achieve – but we all know it isn’t a word. You can’t find love in the dictionary!

We can bring out the other reading by availing ourselves of a convention philosophers care mightily about: when we talk about a word, we put it in quotation marks, thus: “love” is just a word. “Cheeseburger” is just a word. “Word” is just a word. But this isn’t fair, you say. Whoever said that love is just a word meant something else, surely. No doubt, but they didn’t say it.

Norm Geras submits a few of the deepities he’s encountered:

Some deepities I have grown to love and laugh at are these. There’s no such thing as an enduring human nature. Oh, you reply, so human beings don’t need to eat or rest? There aren’t common abilities like the use of language and such? Comes back the reply: we didn’t mean that by human nature; we meant that not all humans are greedy, or power-loving, or interested in unlimited wealth. So it turns out that the denial of an enduring human nature amounts to some changeable or non-universal features of the human character not being unchangeable. What else is new?

In a tutorial I used to run on the Modern Political Thought course at Manchester, I would sometimes ask students if there are any biologically-based differences between men and women. You’d be surprised how many of them answered ‘No’. What?! How about the ability to bear children? Oh… we thought you meant differences like being cleverer or more fit to govern. So there are possible differences then? Yes, perhaps.

Julian Baggini talked to Dennett. On Dennett’s engagement with science and philosphy:

He may not be crudely scientistic, but it is true that these days Dennett spends more time around scientists than other philosophers. “I find the discoveries in those fields mind candy, just delicious,” he says. “If I go to a scientific conference I come away with a bunch of new things to think about. If I go to a philosophy conference I may come away just having learned four more wrinkles in the debate about something philosophers have been thinking about for all my life.”

But Dennett also maintains that we need philosophy to protect us from scientific overreach. “The history of philosophy is the history of very tempting mistakes made by very smart people, and if you don’t learn that history you’ll make those mistakes again and again and again. One of the ignoble joys of my life is watching very smart scientists just reinvent all the second-rate philosophical ideas because they’re very tempting until you pause, take a deep breath and take them apart.”

Recent Dish on Dennett’s tips for arguing here.