Reviewing Worldly Philosopher: The Odyssey of Albert O. Hirschman, Cass Sunstein underscores the remarkable life of the German-born writer and thinker, whose works include The Rhetoric of Reaction and Exit, Voice, and Loyalty:

In dealing with events during the difficult period between 1935 and 1938, Hirschman showed a great deal of resilience and bravery. He decided to fight in the Spanish civil war against Franco with the very first Italian and German volunteers, some of whom were killed on the battlefield. For the rest of his life, Hirschman remained entirely silent about this experience, even with his wife, though “the scars on his neck and leg made it impossible for her to forget.” Returning from the war, he worked closely with the anti-Fascist Italian underground, carrying secret letters and documents back and forth from Paris.

As war loomed between France and Germany, Hirschman became a soldier for a second time, ready to fight for the French in what many people expected to be a prolonged battle. After the French defense quickly collapsed, Hirschman lived under German occupation and engaged in what was probably the most courageous and hazardous work of his life. Along with Varian Fry, a classicist from Harvard, he labored successfully to get stateless refugees out of France. In 1939 and 1940, they created a network that would enable more than two thousand refugees to exit. As Adelman writes, the “list of the saved reads like a who’s who.” It included Hannah Arendt, André Breton, Marc Chagall, Marcel Duchamp, and Max Ernst.

And like his hero Montaigne, doubt was essential to Hirschman’s thinking:

Hirschman sought, in his early twenties and long before becoming a writer, to “prove Hamlet wrong.”

In Shakespeare’s account, Hamlet is immobilized and defeated by doubt. Hirschman was a great believer in doubt—he never doubted it—and he certainly doubted his own convictions. At a conference designed to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of his first book, who else would take the opportunity to show that one of his own central arguments was wrong? Who else would publish an essay in TheAmerican Economic Review exploring the “overproduction of opinionated opinion,” questioning the value of having strong opinions, and emphasizing the importance of doubting one’s opinions and even one’s tastes? Hirschman thought that strong opinions, as such, “might be dangerous to the health of our democracy,” because they are an obstacle to mutual understanding and constructive problem-solving. Writing in 1989, he was not speaking of the current political culture, but he might as well have been.

In seeking to prove Hamlet wrong, Hirschman was suggesting that doubt could be a source not of paralysis and death but of creativity and self-renewal. One of his last books, published when he was about eighty, is called A Propensity to Self-Subversion. In the title essay, Hirschman celebrates skepticism about his own theories and ideas, and he captures not only the insight but also the pleasure, even the joy, that can come from learning that one had it wrong.

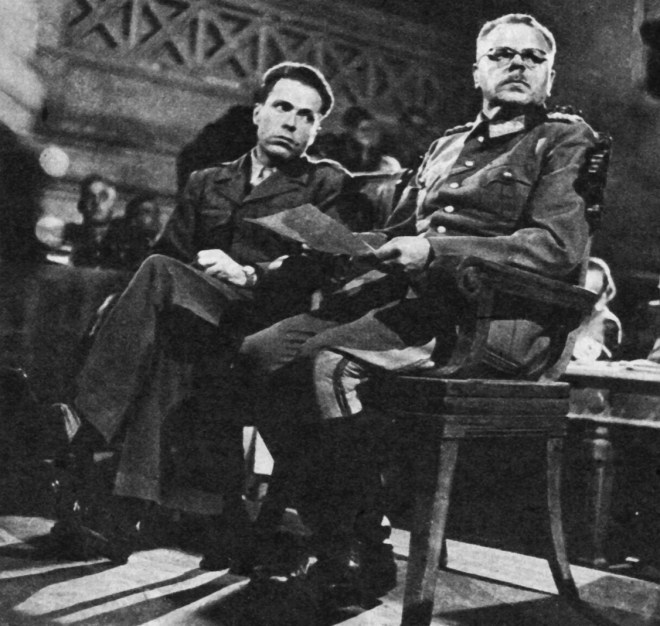

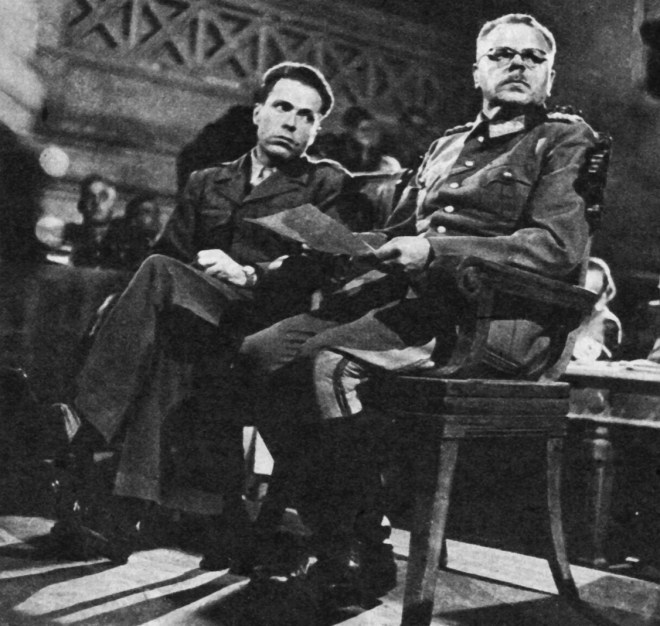

(Photo of Hirschman, on the left, in 1945, serving as a translator during the war crimes trial of German Anton Dostler, via Wikimedia Commons)