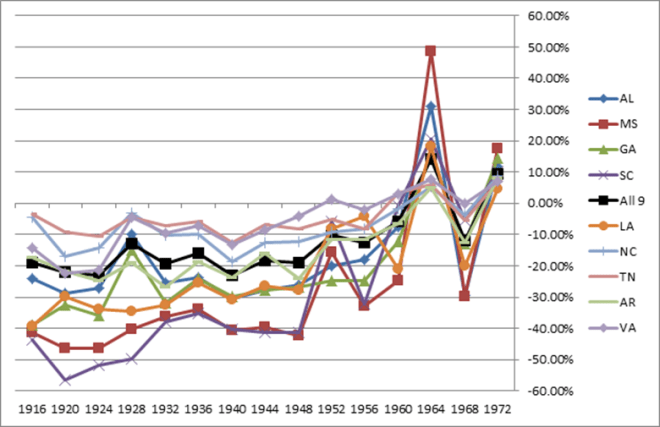

A reader created the above chart:

Last night I decided to fact-check Sean Trende’s argument, namely that:

the white South began breaking away from the Democrats in the 1920s, as population centers began to develop in what was being called the “New South”… . In the 1930s and 1940s, FDR performed worse in the South in every election following his 1932 election. By the mid-1940s, the GOP was winning about a quarter of the Southern vote in presidential elections

The evidence simply does not tell this story. I examined and charted nine southern states: Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, Louisiana and Arkansas (the Confederacy minus Florida and Texas) to see how the Republican presidential candidates performed relative to the nation as whole from 1916 to 1972. There was no improvement by Republican presidential candidates in the south in the ’20s, ’30s and ’40s. In 1916, the GOP ran 18.9% points lower in these nine southern states than the country as a whole. By 1948, the GOP was running exactly … 18.9% points lower. Republicans had a relatively good year in the South in 1928, when Democrats nominated Al Smith, a New York Catholic. Otherwise, GOP presidential candidates traded in a fairly narrow range in the South during these three decades.

Trende says that FDR’s winning margins declined in the South with each election. This ignores that fact that FDR winning margins declined nationwide with each election.

When you adjust for that fact, you can see that Republicans underperformance in the South stayed about the same through four FDR elections with no obvious trend: – 19.4% in 1932, -16.1% in 1936, -23.0% in 1940 and -18.7 in 1944.

Trende says that “by the mid-40’s the GOP was winning about 25% of the Southern vote in presidential elections”. Yes. But in these combined nine Southern states, the GOP had already captured 27.2% of the vote in 1916, 38.2% in 1920, 30.97% in 1924 and 45.16% in 1928. Breaking 25% in the late ’40s was not something impressive or new for the GOP in the South.

Moreover, Trend’s thesis – that affluence spurred by the growth of cities and towns is what drew Southerners to the GOP – is completed belied by the data. The two states with the biggest swings – from monolithically Democratic in 1920s to gaga for Goldwater in 1964 – were Mississippi and South Carolina, two states know more for their deep plantation roots than for bourgeoning metropolises.

Trende is right that a big breakthrough for the GOP in the south came in 1952 (well before the Civil Right Act of 1964). He suggests that this attraction can’t have be driven by racial hostility since Eisenhower was sympathetic to civil rights. However, this totally ignores what was happening on the Democratic side. Southern delegates walked out of the Democratic convention in 1948 when Humphrey called for an end to Jim Crow and formed their own protest party (the Dixiecrats) whose chief objective was to uphold segregation. Shortly thereafter Truman de-segregated the military.

While Democrats still had a large bloc of Southern representatives and would be less supportive of civil rights legislation in ’50s and ’60s because of it, by 1948 the Democratic leadership was signaling that is was no longer going to uphold the Southern segregation. This encouraged many white southerners to abandon the national Democratic party (if not their own local Democratic party just yet) and to view the two parties through the prism of other issues. That is what allowed the GOP to start making big gains in the ’50s and ’60s.

Another reader:

Geez, Trende has discovered something that students of Southern politics have known for a long time: that Republicanism was gaining in the postwar South, at least in the “Rim South.” But he seems unaware of why. Yes, Eisenhower sent the 101st into Little Rock, but he was constitutionally required to uphold federal authority. It was well known that Eisenhower was at best a reluctant supporter of Brown and federal civil rights legislation.

More to the point, the big story in Southern politics after 1948 was the widening gulf between Southern Democrats and the National Party. Not only did you have the short-lived Dixiecrat movement in 1948, but its successors increasingly played footsie with the Republicans without formally leaving the party. Increasingly homeless and unable to make the traditional case that voting Democratic was the best means of maintaining white supremacy, it’s hardly surprising that Southern conservatives who had never especially liked the New Deal would move toward the Republicans. To be sure, Republicans for a long time drew their votes from the urban and suburban middle class; working-class whites remained Democrats, often out of gratitude for the New Deal (I remember sitting in a barber shop in Upstate SC around 1970 hearing an old white guy say, “Don’t tell me about the Republicans; I lived through the Hoover time!”), partly out of hostility to the “country club” set, but in any case because they didn’t have to choose between local Democrats and Republicans on race.

But as long as I’ve been politically aware (and I’m 65, and a lifelong South-watcher), Republicans were openly competing in the South for the anti-civil rights vote, arguing that the real threat to the “Southern way of life” were those traitorous Yankee New Dealers. The first serious statewide run by a Republican in South Carolina was W. D. Workman’s Senate bid in 1962; Workman was a journalist best known for being the author of a segregationist screed titled The Case for the South. This was the face of Republicanism in my home state.

But, again, there was no real difference on race between them and the Democratic establishment in the South until after 1965, when the Democrats executed one of the great pivots in American political history and reinvented themselves as a biracial party. It still took the Republicans some time to supplant the Democrats as the “white” party, though, because of that lingering “country club” stigma; they did so by increasingly openly identifying with white southern culture – Confederacy, NASCAR, Southern Baptist religiosity, the “culture wars” generally.

Yes, it’s a complicated story; but Southern Republicans have exploited, if not racism per se, opposition to government solutions to racial discrimination, for as long as I’ve been alive.