In the late 1950s, Charles E. Dederich, a member of Alcoholics Anonymous, developed his own recovery program called “Synanon.” At its center was “The Game”:

The Game consisted of a dozen or so addicts sitting in a circle. One player would start talking about the appearance or behavior of another, picking out their defects and criticizing their character. But as soon as the subject of the attack tried to defend him-or herself, other players would join the barrage, unleashing a no-holds-barred verbal onslaught.

Vulgarity was encouraged—“talk dirty and live clean,” said Dederich—and so the other members would accuse the defendant of real and imagined crimes, of being selfish, unthinking, of being a no-good, ugly, diseased cocksucker who was too weak to go straight and was too much of an asshole, junkie, cry-baby motherfucker to admit it.

Faced with this unrelenting group assault, the recipient would eventually have little choice but to admit their wrongdoing and promise to mend their ways. Then the group would turn to the next person and begin all over again.

“The first time it hits you, it absolutely destroys you,” remembered a former Game player. “No matter how loud you scream, they can scream louder,” recalled another, “and no matter how long you talk, when you run out of breath they’re there to start raving again at you. And laughing.” Emotional catharsis was the aim. There were only two rules: no drugs, and no physical violence. It was vicious, but it actually seemed to work. “One cannot get up,” remarked Dederich, “until he’s knocked down.”

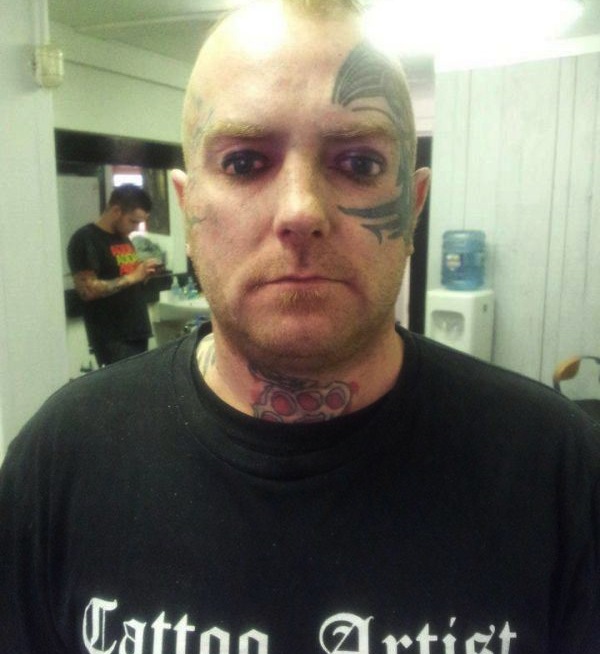

Some NSFW fodder seen above.