The famed author just got some major face-time:

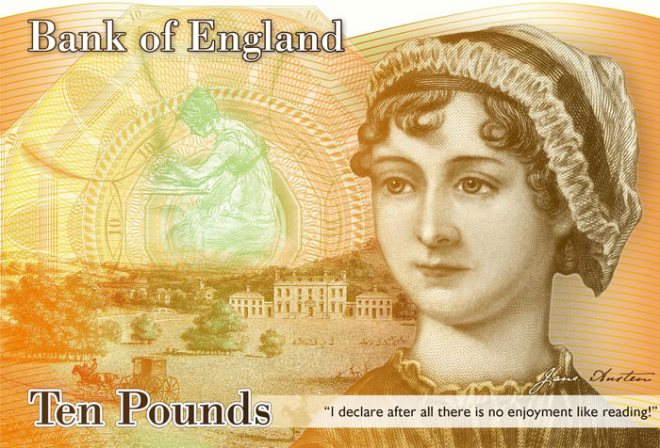

[Bank of England governor Mark] Carney’s announcement [that Jane Austen is going on the £10 note] was aimed at quelling a three-month storm of protest unleashed when [former Bank governor Sir Mervyn King] announced that the only woman to appear on an English banknote other than the Queen–the prison reformer Elizabeth Fry–would be replaced by Winston Churchill, probably in 2016. She and Florence Nightingale are the only two women, other than the Queen, to have appeared on English banknotes since they started portraying historical figures in 1970. Campaigners threatened to take the Bank to court for discrimination under the 2010 Equality Act and launched a petition on the campaign site Change.org which secured more than 35,000 signatures.

Public reaction seems to be largely positive, but Belinda Webb isn’t impressed by the pick:

Jane Austen as a choice of woman to be on the £10 bank note would be fine, if we were in the 18th century. I can’t help but feel she is the safe, bland, acceptable, middle-class choice. Austen is the woman men don’t mind giving us as a representation because she is no threat to the prevailing order whatsoever.

But Austen scholar Bharat Tandon objects to the popular conception of “dear old Aunt Jane”:

[I]t may be that the top brass at the Bank of England have been cannier than they imagined, for Austen was, in her time, one of the most elegantly hard-headed chroniclers of the pressures of money on women. …

It cannot be a coincidence that both of her earliest published novels begin with women suffering under the inequities of the inheritance system. The Dashwood sisters in Sense and Sensibility are suddenly made reliant on their brother and his penny-pinching wife Fanny (“people always live for ever when there is any annuity to be paid them”), and the Bennet girls’ prospects in Pride and Prejudice are constrained by the entail of the family inheritance to their male cousin Mr Collins. It’s hard to read the subsequent romances without feeling the pressure of money, which becomes an invisible but powerful agency, almost a character in its own right, just as it does in later 19th-century novels by Dickens and Trollope.

Meanwhile, Katherine Connell notes that “amusingly, the quote from Pride and Prejudice selected for inclusion on the bill seems to have been chosen by someone who didn’t read the book”:

“I declare after all there is no enjoyment like reading!” were the insincere words spoken by the affected Miss Bingly to Mr. Darcy in a futile attempt to attract his attention:

Miss Bingley’s attention was quite as much engaged in watching Mr. Darcy’s progress through his book, as in reading her own; and she was perpetually either making some inquiry, or looking at his page. She could not win him, however, to any conversation; he merely answered her question, and read on. At length, quite exhausted by the attempt to be amused with her own book, which she had only chosen because it was the second volume of his, she gave a great yawn and said, “How pleasant it is to spend an evening in this way! I declare after all there is no enjoyment like reading! How much sooner one tires of any thing than of a book! — When I have a house of my own, I shall be miserable if I have not an excellent library.”

Austen would no doubt appreciate the irony.