Nice, France, 9 am

Month: July 2013

Help, Thanks, Wow

That’s how the religious writer Anne Lamott summarizes the three essential prayers. Rick Heller translates them for atheists who practice meditation. For example:

The “Wow” comes from attention. When people quiet their internal chatter and really focus on their present experience, they often report that sensations seem more vivid. Eating slowly and mindfully, you notice subtle tastes. Sights and sounds become more striking when you stop to take them in.

On that note, Jim Forest describes how Thich Nhat Hanh, a poet and monk, taught him how to wash dishes:

“Jim,” he asked, “what is the best way to wash the dishes?” I knew I was suddenly facing one of those very tricky Zen questions. I tried to think what would be a good Zen answer, but all I could come up with was, “You should wash the dishes to get them clean.” “No,” said Nhat Hanh. “You should wash the dishes to wash the dishes.” I’ve been mulling over that answer ever since — more than three decades of mulling. But what he said next was instantly helpful: “You should wash each dish as if it were the baby Jesus.”

That sentence was a flash of lightning. While I still mostly wash the dishes to get them clean, every now and then I find I am, just for a passing moment, washing the baby Jesus. And when that happens, though I haven’t gone anywhere, it’s something like reaching the Mount of the Beatitudes after a very long walk.

Capturing Closeness

Alison Barker muses on The Art of Intimacy, Stacey D’Arasmo’s treatise on intimacy’s successful portrayal in literature and art:

[U]nexamined assumptions about something as powerful as intimacy make for stories that are full of stereotypes and stereotypical behavior. This is depressing. And it’s not art. By continually rearticulating how she conceives the different types of intimate relationships wrought by the best writers in this and the last century, D’Erasmo cleverly prepares us to accept that intimacy, necessarily, is a bit of a mystery, and that it is only when writers question their received ideas about intimacy that they are able to transcend sentimentality and produce stories that better illuminate this powerful, mysterious, frequently shape-shifting human experience.

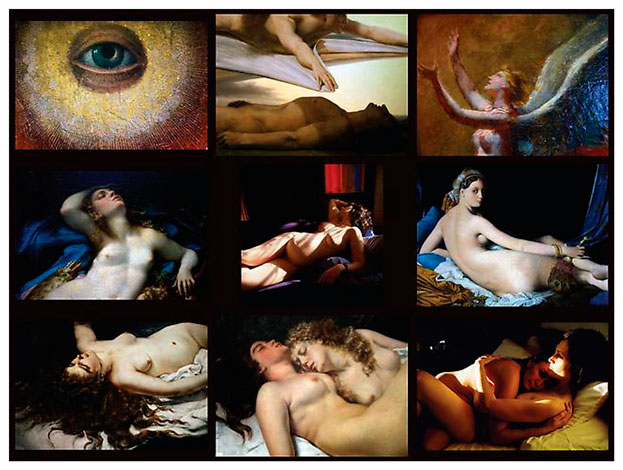

(Photo from Nan Goldin’s Scopophilia exhibit, currently being shown at the Matthew Marks Gallery, “which pairs intensely personal portraits of Goldin’s friends and lovers with classic images from the Louvre” and is featured prominently in The Art of Intimacy. © Nan Goldin, Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery.)

Sex, Drugs, And Rolling Stones

Robert Frank’s 1972 documentary of the Rolling Stones on tour, Cocksucker Blues, portrays the band in such an unflattering light that, upon seeing the completed work, its members blocked its release. Jack Hamilton reviews the movie:

Most troubling of all are the unfamous players, the roadies and groupies and hangers-on who seem plucked from the pages of Slouching Towards Bethlehem and are now lost to history, or to worse. We meet a fan bemoaning the injustice that her LSD usage has caused her young daughter to be taken into protective custody; after all, mom protests, “she was born on acid!” We see a man and woman shooting heroin, filmed with bored detachment, the only sound the whir of a hand-held camera. Upon completion the woman looks up and asks, unnervingly and entirely validly, “Why did you want to film that?”

The film’s most disturbing scene, and the one that most lives down to its reputation, takes place on the Stones’ touring plane.

We see explicit and zipless sex. We see clothed roadies wrestling with naked women in a manner that seems dubiously consensual, as band members play tambourines and maracas in leering encouragement. At one point Keith Richards emphatically gestures at Frank to stop filming; he doesn’t. By the time the scene finally ends we feel drained, nauseated, ashamed of ourselves and everyone else in this world.

These are emotions not typically associated with rock films, and if only for this reason Cocksucker Blues is an important work. But it’s also a riveting portrayal of beauty in decay, and Cocksucker Blues’ most redemptive moments come in its musical performances. Frank has no use for the sumptuous stage sequences of later concert films like Scorsese’s The Last Waltz or Demme’s Stop Making Sense; the performance footage in Cocksucker Blues is frenetic, explosive, and almost random in composition. “Brown Sugar” is captured by a hand-held camera so hyperactive it seems to mimic Jagger’s dance moves; “All Down the Line” is shot almost entirely from behind the drum kit, Charlie Watts’ splashing hi-hat in the foreground, hypnotically obscuring, then becoming, the main event. In a particularly stunning scene Stevie Wonder joins the band onstage for a medley of “Uptight (Everything’s Alright)” and “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” as the camera scrambles about, bottling a moment more intoxicating than every substance backstage combined.

The scene with Stevie Wonder is here. Two long clips from the film are here and here.

The Internet Is For Pornfunding

Gillian Orr ponders the potential of Offbeatr, a site for crowdfunding porn:

This could potentially have a democratising effect on porn, with previously short-changed fans (namely women) being given a say as to the sorts of films that get made. Erika Lust, a feminist writer and director of pornography, isn’t quite so sure: “I don’t think that will be the case. There is still a long way to go until women are considered significant porn consumers as it is. Also, it’s my belief that change in the industry will come from film-makers who are dedicated to creating erotica and particularly their own vision, regardless of funding and popular opinion.”

Lux Alptraum agrees that many projects seems to be faltering but names a notable exception:

Almost a year after the site’s launch, many projects are still struggling to get the votes needed to advance into the funding stage (unlike most crowdfunding sites, Offbeatr requires project creators to collect a set number of votes before they begin soliciting donations as a way of proving the viability of the project). Even some promising projects created by talented, experienced people seem to be floundering. “Come to Me When You Are Ready,” a film by the award winning adult filmmaker Erika Lust, has received a mere 17% of the votes required to move on to the fundraising stage; Mormonboyz.com’s campaign to fund a film scheduled to debut last fall is similarly stalled. …

To date, thirteen projects have been successfully funded by Offbeatr. Most had modest goals, which certainly helped their success (though it should be noted that one project managed to raise almost $200k). And many of them were created by established artists with loyal fan bases — a hallmark of quite a few crowdfunding successes, adult or not. But there is one thing that sets Offbeatr’s successful projects apart from those found on Kickstarter, Indiegogo, or Crowdrise: the majority of them have come from members of the furry community.

In other furry news, WM. Ferguson was in Pittsburgh for the Fourth of July weekend and noticed that, aside from unusually enthusiastic Pirates fans, something about the city seemed strange:

I saw another guy having a cigarette outside the convention center. He had fox ears, a matching tail and big fur boots, and I asked him what was going on. He told me he was in town for Anthrocon — a convention for fans of anthropomorphism, commonly known as furries.

It was a perfect alignment of misunderstood subcultures: Pirates fans and furries. The furries’ ascendancy seems the more assured of the two. Although the Pirates had the best record in baseball the weekend I was in Pittsburgh — which hasn’t happened this late in the summer since I can’t remember — Anthrocon was having its strongest convention ever, having grown to more than 5,000 furries since it started in Albany for a few hundred like-minded anthropomorphs in the late ’90s. This year, The Post-Gazette estimated, Anthrocon would bring an estimated $6.2 million to the city. The attendees would also try for the world record for the largest parade of people in fur suits.

Previous Dish on Offbeatr here.

The Original Erotic Novel

Ruth Graham provides a brief history of Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, or “Fanny Hill,” the 18th-century novel that, in the 1960s, challenged the Supreme Court to defend the literary merits of so-called “pornographic” texts:

The 1749 novel … depicts a broader range of sexual experiences than any available book written before it in English, and, for that matter, than almost any major novel

written since. The plot follows a newly orphaned 15-year-old as she makes her way to London, falls in with a madam and some prostitutes, enthusiastically embraces her new career in “profit by pleasing,” and finally marries the man who deflowered her. But the plot is merely a rickety scaffolding for what is essentially a series of explicit sexual encounters that the heroine either gleefully performs—”what floods of bliss! what melting transports!”—or witnesses through a variety of far-fetched spy tactics. …

[T]he legal victory for “Fanny Hill” did more than just improve the novel’s reputation. [Scholar Hal] Gladfelder calls the obscenity trials of the 1960s some of the key cultural events of the decade. “Some people will think for worse, and others will think for better, but it did sort of open the floodgates,” he said. “It was like a melting iceberg. There was nothing left to justify prosecuting or censoring these books.” Law enforcement around obscenity is now primarily concerned with child pornography, and the only other major restrictions on adult pornography have to do with where it is displayed and advertised. Today, obscenity charges for text-based materials, let alone historic literature, are almost unheard of.

More than 250 years after “Fanny Hill” boosted its author out of debtors prison, the book still has the capacity to shock. As [assistant attorney general William I.] Cowin noted in front of the Supreme Court, after the first 10 pages of the novel, “all but 32 have sexual themes.” But “Fanny Hill” would not have survived so long if it were merely scandalous in 18th-century terms: It remains revolutionary today because, as English critic Peter Quennell wrote in the introduction to the 1963 edition, “It treats of pleasure as the aim and end of existence.” Yes, Fanny issues a perfunctory ode to virtue at end of the novel, but she isn’t punished for her past vices, and we sense she’ll continue to enjoy herself. The man she first loved—and first loved sleeping with—returns to marry her, and he’s rich, too. “Fanny Hill” is a novel narrated by a woman who gets to have it all: sex and love, experience and stability.

Peruse the text here.

(Image: “Fanny Emboldens William,” by Édouard-Henri Avril, via Wikimedia Commons)

Technology’s Sex Drive

Michael Moran claims that “in peacetime, sex is technology’s primary driver”:

It’s been suggested that it was the greater availability of porn on VHS formats that helped it to win the video format wars over Betamax. And there’s a reason why Polaroid’s innovative camera that eliminated embarrassing trips to the chemist was called the Swinger.

Nowhere is the pornographers’ symbiotic relationship with technology more evident than online. Back in the 1990s, when the internet explosion was a mere spark, Penthouse was handing out modems to subscribers. By 2010, out of the 1m most visited websites, around 50,000 carried erotic content. Live internet chat, be it Snapchat or grownup video-conferencing, has its genesis in the porn industry. LiveJasmin.com is the world’s most visited porn site and one of the most successful websites of any kind. Of the estimated 1bn regular internet users, around 2.5% visit that one site at least once a month.

Heroines Without The Romance

Kelsey McKinney praises Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping as a rare example of a female-centric book that lacks a love plot:

There are not many books that star a woman without a man to hold her hand and guide her, or a mess of domestic tasks for her to attend to as her first priority. In the 33 years since Housekeeping’s publication, few–if any–books have mirrored Robinson’s example. Female protagonists like Orleanna Price of Barbara Kingsolver’s The Poisonwood Bible or Margaret Atwood’s Offred in The Handmaid’s Tale, participate in political agendas, fight in wars, and generally have goals other than their love lives. Likewise, some popular fiction has begun to feature leading women with larger career goals and less focus on love. Skeeter of The Help by Kathryn Stockett chooses her career over love as do Edna Pontellier of Kate Chopin’s The Awakening and even Andrea Sachs of Lauren Weisberger’s The Devil Wears Prada. These women and their goals are the main thrust of these novels, but they all include a love subplot. …

A book about women that isn’t a book about love simply isn’t normal. But the plot line is. Women are increasingly pursuing careers, educations, and themselves far before they begin to pursue men, and their stories need to be told. … Books that tell tales of girls learning to be themselves the way that many girls growing up today will: alone.

Mental Health Break

Google Street View abstracted:

The Words He Carried

The late Roger Ebert penned a love letter to poetry before he died. It was just published in the latest issue of Poetry magazine. This is how it begins:

Many lines of poetry are so long-embedded in my memory that I find them appearing when I speak or write. Sometimes I am quoting. Sometimes I am unconsciously drawing from the reservoir. Some poets lend themselves to that, because they have found a way to say something important in words that seem almost inevitable. These words for the most part I made no effort to memorize. They simply found a place for themselves, and they stayed.

One poem I deliberately set out to memorize. In the eighth grade Sister Rosanne required us all to learn a poem by heart. I was assigned “To a Waterfowl,” by William Cullen Bryant. For years thereafter I regaled listeners with as much of it as they desired:

Whither, ’midst falling dew,

While glow the heavens with the last steps of day,

Far, through their rosy depths, dost thou pursue

Thy solitary way?