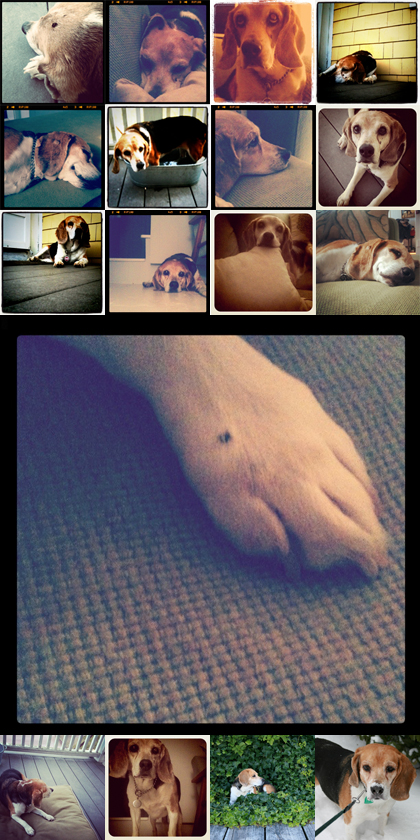

It’s not as if I have any excuse (you warned me plenty of times) but I’m shocked by how wrecked I am right now. Patrick, Chris and Jessie, thank God, have been holding down the fort on the Dish, because otherwise I’m not sure I could think about much else right now. How can the emotions be this strong? She was a dog, after all, not a spouse or a parent.

It’s not as if I have any excuse (you warned me plenty of times) but I’m shocked by how wrecked I am right now. Patrick, Chris and Jessie, thank God, have been holding down the fort on the Dish, because otherwise I’m not sure I could think about much else right now. How can the emotions be this strong? She was a dog, after all, not a spouse or a parent.

And yet, today, as I found myself coming undone again and again, I realized that living with another being in the same room for 15 and a half years – even if she was just a mischievous, noisy, disobedient, charming, food-obsessed beagle – adds up to a lot of life together. I will never have a child, and she was the closest I’ll likely get. And she was well into her teens when she died.

She was with me before the Dish; before my last boyfriend, Andy; before I met Aaron. She came from the same breeder as the beagle my friend Patrick got as he faced down AIDS at the end of his life. I guess she was one way to keep him in my life, so it was fitting that his ex-boyfriend drove me to the farm in Maryland to get her. I was going to get a boy and call him Orwell (poseur alert) but there were only girls left by the time we got there. I didn’t know what I was doing but this tiny little brown-faced creature ambled over to me and licked the bottom of my pants. She chose me. On the ride home, I realized I hadn’t thought for a second what to call a girl dog, and then Dusty Springfield came on the radio.

My friends couldn’t believe I’d get a dog or, frankly, be able to look after one. I was such a bachelor, a loner, a workaholic writer and gay-marriage activist with relationships that ended almost as quickly as they had begun. I thought getting a dog would help me become less self-centered. And of course it did. It has to. Suddenly you are responsible for another being that needs feeding and medicine and walking twice a day. That had to budge even me out of my narcissism and work-mania.

But I also got her as the first positive step in my life after the depression I sank into after my viral load went to zero in 1997. I know it sounds completely strange, but the knowledge of my likely survival sent me into the pit of despair. I understand now it was some kind of survivor guilt, and, after so much loss, I had to go through it. I wrote my way out of the bleakness in the end – as usual. But this irrepressible little dog also pulled me feistily out.

She was entirely herself – and gleefully untrainable. I spent a large part of our first years together chasing her around bushes and trees and under wharfs, trying to grab something out of her mouth. She’d find a disgusting rotten fish way underneath a rotting pier, wedge herself in there, eat as much as she felt like and then roll around in ecstasy as I, red-faced, bellowed from the closest vantage point I could get. There was the year that giant tuna carcass washed up on the sand and I lost her for a split second and nearly lost my mind looking for her until I realized she was inside the carcass, rendering herself so stinky it was worse than when she got skunked. But the smile on her face as she trotted right out was unforgettable. It was the same, proud, beaming face that appeared from under a bush in Meridian Hill Park covered in human diarrhea, left by a homeless person. Score!

Good times: the countless occasions she peed in the apartment, always under my blogging chair, driving me to distraction; her one giant chocolate orgasm, when she devoured two boxes of Godiva chocolates left on the floor by a visiting friend, ate every one while we were out at dinner, and then forced me to chase her around the apartment when I got home, as she puked viscous chocolate goo over everything, until I slipped in it too. Yes, she survived. The rug? Not so much.

She was also, it has to be said, always emitting noise. She had a classic howl, and when the two of us lived in a tiny box at the end of a wharf, she would bay instinctively at every person and every dog she saw come near. It’s cute at first. But after a while, she drove most of my neighbors completely potty. I tried the citronella collar, but she found a way to howl that stayed just below the volume that triggered the spray. Howling was what she did. There was no way on earth I was going to stop it.

But there was one exception to this rule. In my bachelor days, I’d stay out late in Ptown, trying to get laid, and often getting to sleep only in the early hours. I installed some floor-to-ceiling window blinds to block out the blinding sun over the water – so I could sleep late (this was before the blog). Dusty – usually so loud and restless – would wait patiently for me to wake up, and wedge herself between the bottom of the fabric of the blind and the glass in the window. That way, she kept an eye on all the various threats, while basking in the heat and light of the morning. And until the minute I stirred, despite all the coming and going around her, she uttered not a peep. In her entire life, she never woke me up. This is the deal, she seemed to tell me. You feed and walk me and house me on a beach all summer long, and I’ll let you sleep in.

It was a deal. She never broke her part of it; and I just finished mine.

(Photo montage by Aaron Tone.)