Sarah Sloat doubts that new technologies will be enough:

In his “silicon gospel” (as it’s described by the Los Angeles Review of Books), Byron Reese considers agricultural technologies like genetic engineering and automated farms as the way to feed every starving mouth. The idea that increased food production—made possible by new inventions and genetically modified crops—will solve hunger isn’t necessarily a unique one. CropLife America, a U.S. trade association, uses this argument when advocating their clients: Food production capacity is endangered by an ever growing population. So, a faction of the tech world’s solution is as follows: We need more food. And the only way to grow more food is better technology.

Except, no.

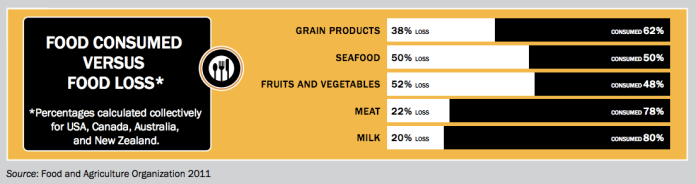

The USDA says that our food waste is equal to 30 or 40 percent of the national food supply. In a 2012 paper, Rebecca Bratspies, of the CUNY School of Law, makes the case that increased food production is not the way to resolve food insecurity. Rather, the problem comes from food distribution. For the past decade, she says, food production has increased faster than population growth. Yet, in the past 35 years, the number of people experiencing food insecurity has nearly doubled: 500 million experienced hunger in 1975; by 2010, it was 925 million. Food production doesn’t alleviate poverty, Bratspies argues; it’s a “social commitment to an equitable distribution of food” that will actually help those suffering.

(Chart: Natural Resources Defense Council)